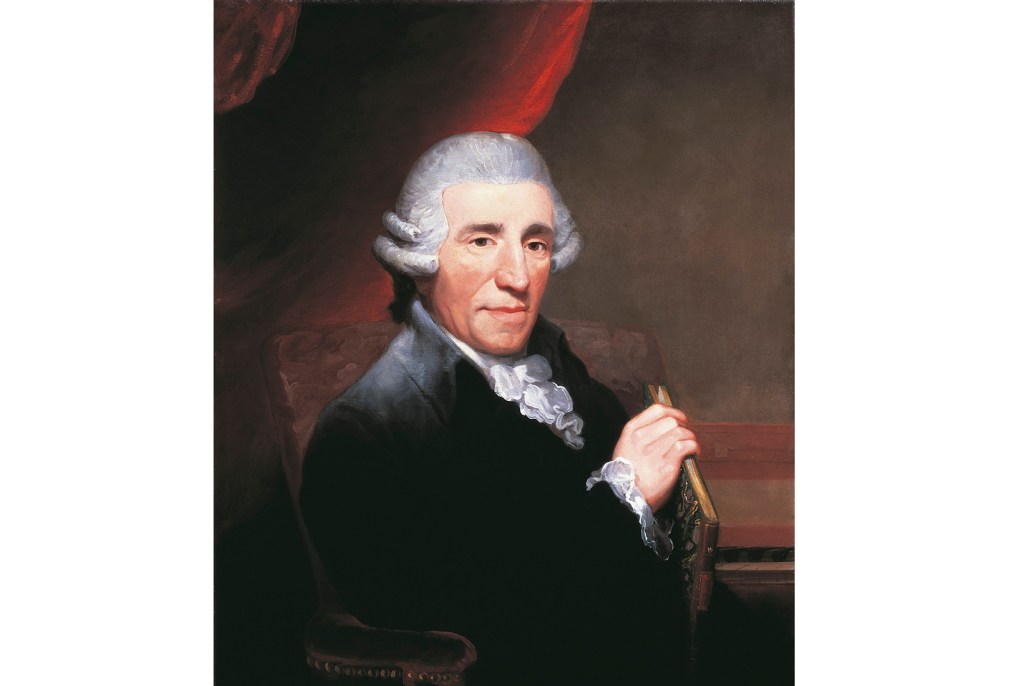

As Joseph Haydn was getting out of bed on the morning of 10 May 1809, a cannonball landed in his back garden. Napoleon’s armies were closing on Vienna, and Haydn’s suburban home was in the line of fire. His valet recorded that the bedroom door blew open and every window in the house rattled. Shaking violently, the 77-year-old composer’s first thought was for his household, which at that point comprised six servants and a talking parrot who addressed him as ‘Papa’. ‘Children, don’t be afraid, for where Haydn is, nothing can happen to you,’ he shouted.

This was nothing particularly new. Over a long life Haydn survived smallpox, saw his house burn down (twice) and narrowly escaped castration at the hands of an overenthusiastic choirmaster. Yet he remained an optimist — by all accounts, a man of deep generosity and warmth, who infused his most human qualities into his music. Mozart converses with angels. Beethoven storms the heavens. But Haydn pours out a big glass of Tokaj and invites you in for a really good chat. Describing his recovery from depression in 2004, The Spectator’s pop critic Charles Spencer wrote that Haydn’s ‘geniality and sanity’ reached him when no other music could.

Since lockdown, I’ve had Haydn’s string quartets on continuous play; a relatively new experience because these pieces — some 70 in total — have been my greatest delight as an amateur cellist, and once you’ve played a Haydn quartet, mere listening rarely comes close. Imagine taking part in a four-way conversation in which you’ve miraculously acquired the eloquence of Johnson and the wit of Wilde; in which everyone is their best self, and that zinger of a one-liner that you’d normally remember half an hour too late is there on your lips at precisely the moment you need it.

I’ve been trying to find recordings that convey that same immediacy and zest. So far, it’s an incomplete and subjective list, with only one real guiding principle: is this performance good company? Starting with the six quartets Opus 9 of 1769 (like many 18th-century composers, Haydn issued his compositions in six-packs), it’s useful to know that the bargain stuff is often as good as the pricier vintages. In Op.9, Haydn hasn’t quite outgrown the mannerisms of his baroque predecessors. But the Kodaly Quartet, on Naxos, plays with red-blooded verve: one sip, and you can feel the color returning to your cheeks.

For Op.20 (1772) I cheated a bit — the Dudok Quartet of Amsterdam recorded three of the six in 2019 (the remainder are due out this May). Their Haydn is elegant and effervescent, the temperamental opposite of the Barcelona-based Cuarteto Casals, whose Op.33 quartets (1781) combine needlepoint brilliance with a flashing, theatrical sense of fantasy — exactly as they should, because Op.33 is where Haydn achieves escape velocity. Four instruments become four personalities; commenting, conversing, laughing. It’s the birth of comedy in instrumental music, and Mozart (who studied these works intensely) could never have written Figaro without it. The Cuarteto Casals makes this revolution sound like a glorious improvisation.

For much the same reason, in Op.50 (1787) I’m completely smitten with a young French ensemble, Quatuor Zaïde. Don’t miss the finale of Op.50 No.6 where Haydn creates a melody with a single note as the player rocks crazily between two strings. Schoenberg, 124 years later, would call this Klangfarbenmelodie; Haydn just smiles. With Op.54 (1788), seasoned quartetters home straight in on the extraordinary Adagio of the second quartet, a wild, impassioned gypsy fiddle solo more than a century ahead of Bartok. The Quatuor Ysaÿe pretty much nails it.

The Op.64 quartets of 1790 might be the most lovable of the lot. You can’t really go wrong, but the Medici Quartet gets my vote for sheer high spirits and charm. By Op.76 (1797) Haydn has returned from his two trips to London, intensely aware that he’s no longer writing merely for four friends in a drawing room, but for the world. These are quartets on a symphonic scale, anticipating Beethoven, Brahms and even (in the rapt, spiritually charged Largo of No.5) Bruckner, and the Takacs Quartet accords them the seriousness, as well as the imagination, that they demand.

By now, Haydn was in his late sixties: his creativity was ablaze, but his body was failing. He abandoned Op.77 (1799) after completing two quartets, and, in his unfinished Op.103 (1803–5), signed off for ever with a desolate little postscript: ‘Gone is all my strength, old and weak am I.’ You wouldn’t guess it from these two masterpieces — simultaneously playful and visionary — and no group performs them with more insight and wonder than the Viennese period-instrument pioneers Quatuor Mosaïques.

But that’s just one approach. In his last years, Haydn expressed the hope that his music might ‘some day, become a spring from which the careworn may draw a few moments’ rest and refreshment’. In truth, there’s refreshment here to last a lifetime.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.