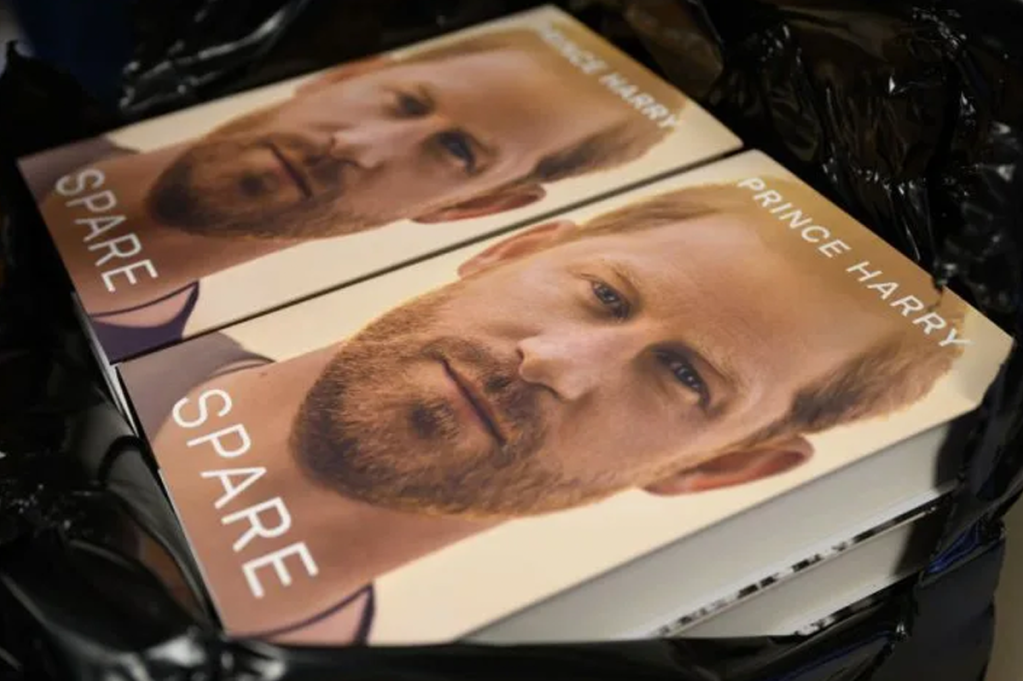

The epigraph for Spare, Prince Harry’s frenziedly awaited memoir, is from William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun. It states simply “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” As a gesture of authorial intent, it’s a bold one. It suggests from the outset that this is not going to be some backwards-gazing book, but instead that it is going to be fully engaged with the present. Given the fact that Spare’s publication has dominated headlines for days, it’s not an inaccurate statement.

Yet — how best to put it? — Harry has never struck most of us as the kind of man who habitually quotes Faulkner. His Pulitzer Prize-winning ghostwriter J.D. Moehringer (credited in the acknowledgements as “my collaborator and friend, confessor and sometime sparring partner”), however, seems like someone who might. So it’s something of a surprise when Harry announces, early in the book, that he discovered the quote on BrainyQuote.com, before he asks “Who the fook is Faulkner?”

We all know who the fook Harry is, though. It’s impossible to come to Spare without the weight of expectation overwhelming it. It’s the first autobiography to be written by a member of the British royal family since the Duke of Windsor’s A King’s Story in 1951. Although that one caused no end of controversy when it was published, it didn’t contain a description of the duke losing his virginity (which reads just as cringe-makingly in context here as it did in the leaked extracts, although “ass” has become “rump”) nor his youthful penchant for drugs. Neither does it contain the notorious description of how he killed twenty-five Taliban fighters during his military service — which, to be fair, makes a great deal more sense here than it did in the leaks.

Just as the Duke of Windsor collaborated with an American author, Charles Murphy, on his autobiography, so Moehringer’s influence can be seen. The chapters — 232 of them in total — are short and concise; the lean and economical writing owes a debt in equal part to Faulkner (naturally), therapy-speak and airport bestseller novels. This is a book in which italics are used to denote speech, where sentences. Exist in. A couple. Of meaningful. Words, and in which Harry has to portray himself simultaneously as the ultimate insider, giving his readers a privileged insight into life in the bosom of the royal family, and an outsider, fleeing an archaic and outdated institution in favor of a new life in California.

Still, of everything that Harry has been associated with since his quasi-abdication in 2020, this is the most interesting endeavor, even if it’s not wholly successful. Perhaps if it hadn’t been spoilt by the pre-publication leaks, it might have greater emotional and literary effect. Nevertheless, there is a great deal of filler between the genuinely interesting segments, most of which revolve around the ever-compelling Windsor family dynamic.

You can detect Moehringer’s influence throughout; not just in the distinctly American prose, but also in the narrative arc. It begins with a genuinely affecting prologue, detailing his discovery of his mother’s death and its aftermath, and then we’re into the usual bildungsroman territory: schooldays, army life and career, relationships with “Mummy” and “Pa” and a tempestuous, love-hate dynamic with “Willy,” the heir to his spare. Surprisingly, he is the main antagonist of the book, other, of course, than the hated media. It’s heavy on introspection and perfectly readable, if lacking in the surprise value it might have had. Harry isn’t afraid to portray himself as a little boy lost, but sometimes it does verge on “poor me” self-indulgence. You can almost hear his therapist’s voice: “Go on, let it all out… scream, man, scream!”

The book’s third section, the “Invictus”-referencing “Captain of my soul,” is its most compelling. It is, of course, largely about “Meg,” and there is yet more of the sentimental gush that anyone who suffered through Harry and Meghan will be familiar with. But it is also here that the narrative really grips, as Harry attacks the “novella” and “sci-fi fantasies” peddled by the tabloid press: the famous quote “whatever Meghan wants, Meghan gets” is singled out for particular ridicule.

Harry takes aim at his family for what he describes as their craven complicity in the face of the all-devouring tabloid media. Charles is quoted as saying “you must understand, darling boy, the institution can’t just tell the media what to do” — remarks which may be on the nose, but perfectly encapsulate his son’s bubbling grievance.

The content may be familiar, but the anger with which it’s written is engaging and vivid. The story comes to life on the page in a way, strangely enough, that it never has in any of Harry’s endless televised interviews. When it’s back to Meg and sentiment and name-dropping, it sags once again; we never forget, for all of Harry’s purported everyman qualities, that he’s the sort of man who is invited by Elton John to come to his home in France to escape the cares of the world.

The much-ballyhooed appearance by a medium who purports to pass on a message from Diana comes at the end, and provides a cathartic climax of sorts, even as Harry acknowledges “the high-percentage chance of humbuggery.” (Moehringer, if we can ascribe such turns of phrase to him, has an arrestingly vivid style, when he’s allowed to flex his literary muscles.) Then there’s some overwritten stuff about a hummingbird flying away (metaphor alert!) and the 407-page long book concludes, with more of a whimper than a bang. No doubt the paperback will have an extra chapter dealing with the Queen’s death and the extraordinary controversy that has occurred ever since.

Still, there’s a laugh to be had at the end, as the back cover of the dustjacket solemnly describes Harry as “husband, father, humanitarian, military veteran, mental wellness advocate and environmentalist.” Some will finish this obviously heartfelt and never less than interesting book and think that the missing word is “author.” Other, less partisan, readers may think that “provocateur” should be supplied. If you loathed him before coming to this book, this is unlikely to engender sympathy, and if you’re Team Harry, then this will be a stirring rallying cry.

For the rest of us — if there is anyone in between — the next step will be to await his wife’s inevitable memoir. My money’s on it being called Care. Will readers? I wouldn’t bet against it, if her husband’s book sells the millions that it undoubtedly shall.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.