Let’s say you have a diagnosis of autism, depression or anxiety. You sleep too much or too little. You masturbate too often. You play computer games and don’t open the curtains. You have no money and you are often profoundly lonely and frequently bored. From this unedifying starting point, can you, let’s say, weightlift your way out of misery? Can you trick yourself into being sociable? Can you ultimately get beyond your fantasy that a woman will save you (she won’t) and learn to live with everyday misery?

Alex Lee Moyer’s documentary TFW NO GF, internet-speak for ‘that feel(ing) when no girlfriend’, is the first attempt to make cinema out of incel subculture (and perhaps thereby also signaling its end). Is it even possible to translate the fast-moving, often-undecidable tone of the internet into the much slower medium of film? Moyer does a great job, flashing up anonymous forum posts and tweets, explaining who various meme characters are, such as ‘Wojak’, a worried-looking man with a bald head, who forms the basis for hundreds of thousands of increasingly outlandish permutations. In this world, originality is encouraged, and on anonymous forums, you are only as good as your last post — there is no hierarchy, only glorious and bloody anarchy (the film is dedicated to ‘Anon’, which seems only just).

Moyer mixes online clips with voice-overs and interviews with several young men who tweet sentences such as ‘Everything feels wrong’ and who describe their futureless, dissociated lives, talking about ‘the normal really weird depressed shit you find yourself doing and don’t really know why’. The internet becomes their home, where connection is generated through the wires, rather than in real-life communities.

Does the internet therefore encourage or create incels (short for ‘involuntary celibate’), or does it rather permit a perennial type to meet and relate, to ‘flirt with their despair’, as one interviewee, Sean, puts it? There is no doubting the ‘edginess’ of incel culture — slurs, insults, pictures of guns and exhortations to suicide are all common. The interviewees mention the gore and hardcore pornography they’ve been looking at since they were children. ‘I’m not a misogynist i just hate women’ tweets one. At one point, one of the interviewees, Charels, tweets ‘one ticket for joker please’ posing with a couple of guns and is arrested, and his guns confiscated. His case is later dismissed on the basis that satire is protected under the First Amendment. His firearms are returned. He later gets a girlfriend.

In a short video from 2017 included in Moyer’s film entitled ‘Take the Black Pill’, Egg White, a pasty-looking man in a check shirt with dark circles under his eyes, sitting in his car and smoking (there is a lot of jittery smoking in this film), tells his audience: ‘You’ve already lost, you’ve already failed.’ He is ‘blackpilling’ his audience, telling them the horrible, nihilistic truth. Well, you have to admit, depression is one way of looking at the world, and it’s not necessarily wrong.

Kyle in El Paso, an energy-drinking Stetson-wearing lonesome cowboy for the internet age, tweets in a broken way: ‘There’s a lot of songs about divorce and breaking up but where’s the songs about not having anyone in the first place.’ Several of his friends have overdosed or, lately, driven their car into a wall. ‘That was like my last friend,’ he says. ‘I’ve always felt lonely, but now I’m really alone.’ Later we see him slightly happier: ‘As long as you’re out of your house, you feel like you’re doing something.’ The lockdown might perhaps make us understand the plight of the incel all too well.

It is impossible not to feel affection for these men. This, indeed, is Moyer’s point. The mainstream response to the film has, however, demonstrated its discomfort with Moyer’s humanizing and de-anonymizing of people the media would prefer to demonize at a distance. Rolling Stone patronizingly chastises Moyer for the sympathy she feels for her subjects and for not using talking heads to discuss ‘incel culture’. But Moyer’s refusal to do so — and why should she — in fact is the point: you don’t need some academic ‘expert’ to tell you about alienated young men when they can do it a hundred times better themselves. As Sean puts it: ‘If you look at the graffiti in Pompeii there’s people TFW No GF posting.’

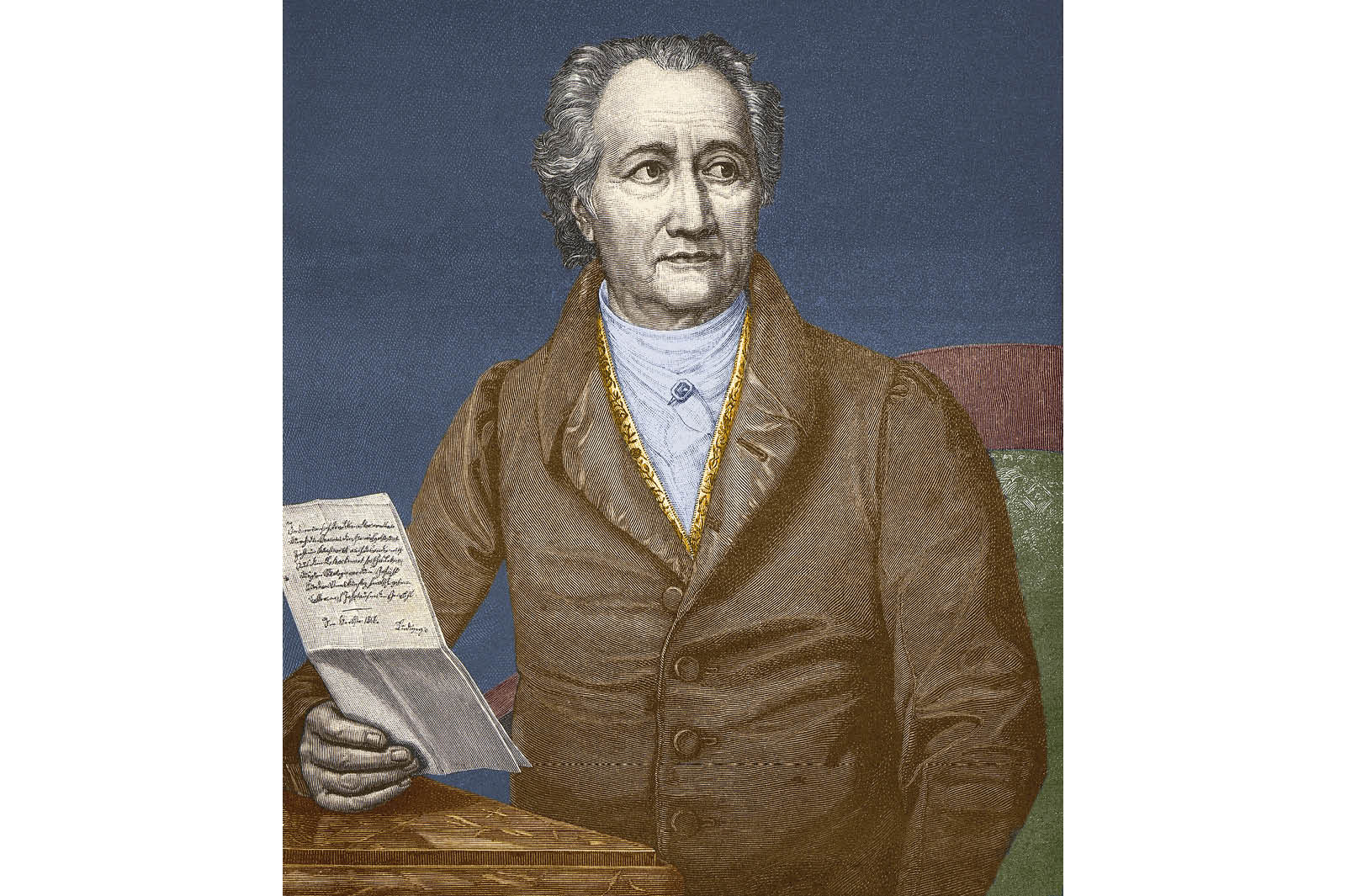

The depressed young man has always been a problem, not least for himself. In 1774, still in his mid-twenties, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published The Sorrows of Young Werther, a loosely self-referential epistolary novel that recounts an unrequited love affair that culminates in poor Werther’s suicide. Painfully in love with the already engaged Charlotte, Werther imagines that she alone could fulfill him: ‘Alas! the void the fearful void, which I feel in my bosom! Sometimes I think, if I could only once but once, press her to my heart, this dreadful void would be filled.’

Where Werther has nature (‘Every tree, every bush, is full of flowers’), the incel has internet forums, memes and Twitter. Just as Goethe was blamed for the cult that formed around Werther, which induced young men to dress like the character, and even occasionally to commit suicide in his name, the young, alienated, depressed men of today are similarly demonized and feared, held responsible for everything from Trump’s election to mass murder, hateful memes to misogyny.

But these men, in their late teens and twenties, exist, and nobody (as yet) loves them. Desire, and life, we must admit, are unfair — the guy does not get the girl, other people are more successful and better-looking than you. But what if your job, if you even have one, is a dead-end, you live in a one-bedroom apartment with your mother, and you have no friends.

[special_offer]

Like every great subculture, identifying with the worst aspects of your life and banding together with others who feel similarly creates extraordinary things. The anonymous internet forums that produce magnificent memes — truly the artform of our times — thrive on transgression, laughter, cruelty, but often, at the same time, a deep sense of empathic suffering: what is it like to have no girlfriend, to have no obvious way of getting one, and to live nowhere-pretending-to-be-somewhere with only your computer for company? The internet is not opposed to ‘real life’, which in any case, if it exists, is probably not going to serve you particularly well. ‘[The internet] is real life,’ says one interviewee, Viddy. ‘You can’t really decouple the two any more.’

There is a deep seam of autodidacticism at work online, beyond, and opposed to, the insanely expensive and increasingly censorious universities. The world that Moyer depicts has its own philosopher, in the shape of Kantbot, a man internet-famous for suggesting in a news interview in New York on US election day 2016 that, among other things, Trump would complete the system of German Idealism, a frankly incredible piece of real-life trolling that is very much worth watching. The roly-poly, glasses-wearing man behind the Twitter-handle is, in all seriousness, perhaps the greatest literary critic of the internet age, and a deeply compassionate man, currently residing in New York, and a master of irony. He reads Friedrich Schlegel on aphorisms. He listens to the young men who write to him in their misery, and sends them reading lists. He writes beautifully: ‘Tweets are shattered remnants of yourself strewn across the plain, the wreck resulting from the collision of the self with existence.’

The taste for fragments, such as anonymous forum posts or tweets, is, to return to our Eternal Incel, much older than the internet. Defending epic poetry in 1813 against jaunty newcomers such as Byron, Francis Jeffrey, editor of the Edinburgh Review wrote: ‘The Taste for Fragments, we suspect, has become very general, and the greater part of polite readers would no more think of sitting down to a whole epic than to a whole Ox.’ The romantic, ironic or experimental fragment lives on in the tweets of disaffected young men, who, despite claims to the contrary, do not seem to want to blame others for their distress, but only to want to create anarchic community out of the wreckage.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.