Back in February, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz gave one of the most important speeches in his country’s post-Cold War history.

In it, Scholz announced that the Russian invasion of Ukraine had produced a zeitenwende, or turning point, and that German policy must adapt. No longer could his nation live on the so-called peace dividend that the West has enjoyed for nearly three decades, and no longer could Germany be dependent on cheap Russian gas. Within three days of Putin’s invasion, Berlin had done a 180, promising to give Ukraine lethal aid, to spend a one-time $110 billion on the Bundeswehr (the German military), and to spend 2 percent of GDP on defense. The failed policies of Scholz’s predecessors that brought Germany so close to Moscow were utterly rejected. The country had learned its lesson.

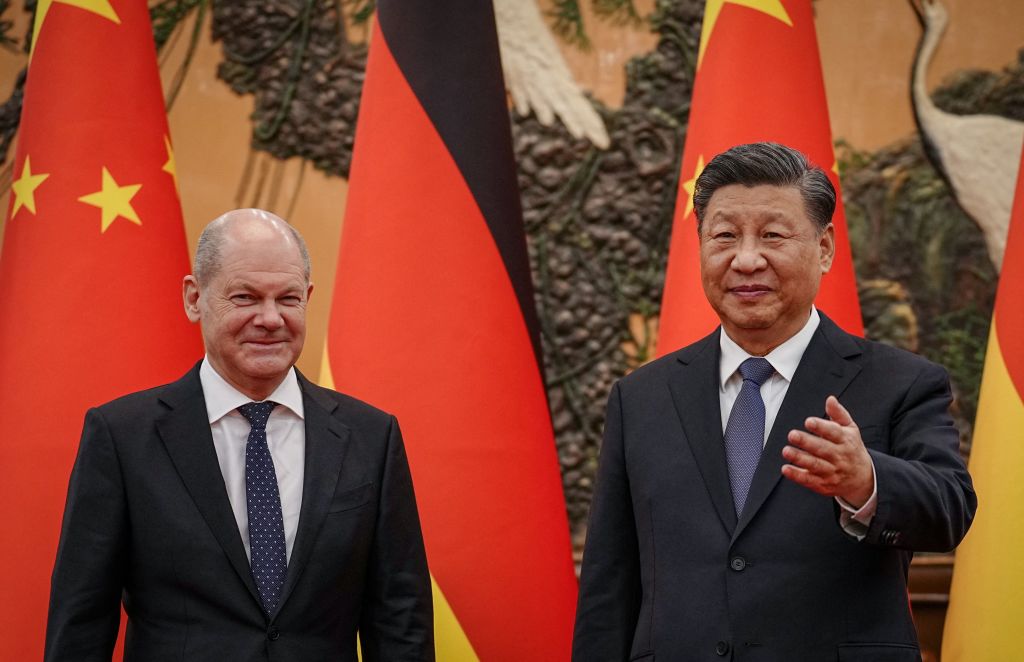

Well, at least so it seemed. While Scholz has stuck to almost all of the promises he made that day, German foreign policy towards the other major threat to world peace — China — has not fared so well. The chancellor is scheduled to meet Chinese president Xi Jinping on November 4, a trip that is not viewed fondly by Germany’s allies.

On Thursday, likely with an eye towards explaining why he was going to visit the communist leader, Scholz wrote a lengthy op-ed in Politico. In it, he recognized that the China of Xi’s third term is nothing like it was in his first, asserting that, in relation to the recently ended 20th Communist Party Congress, “avowals of Marxism-Leninism now take up a much broader space.” He declared that Germany will reduce its dependencies on critical goods and materials from China, recognizing that it does not want a repeat of Nord Stream. He also wrote that Berlin needs to be frank with China, willing to confront it on its extensive human rights abuses.

While this might sound good, upon further inspection, the comments reveal a troubling stubbornness. Scholz refuses to recognize that there is, in fact, a new cold war, and just as Germany did not have the luxury of sitting on the sidelines as Russia menaced Europe, so too will it not be able to avoid this conflict. Such denialism is exactly what enabled Putin’s invasion in the first place.

While it’s good that Scholz wants to break certain dependencies on China, he is missing the most fundamental dependency of all: the broad reliance that the German economy has on China. As of 2021, China was Germany’s largest trading partner, conducting over $246 billion in trade. Companies like Volkswagen are also highly dependent on China, with sales to that country constituting more than double their second largest market, Western Europe. Not surprisingly, the German Automobile Association is quite happy with Scholz’s visit. This kind of reliance on Chinese cash is as (if not more) potent as reliance on Russian gas. (The US is just as guilty, but at least in its case, China is equally dependent, and Washington is actually willing to stand up to China and project power abroad in defense of freedom.)

What about human rights abuses? Even here Scholz does not say anything revolutionary. He writes that Germany and China “will not avoid difficult issues in discussions with one another.” This is the classic modern European response, all words and no action. It is easy to have frank talks; it is hard to take concrete actions, like implementing sanctions. Germany has not even taken the simple and symbolic step of declaring the mass persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang to be a genocide, something many other countries have already done.

Now to the issue that has generated so much criticism: Chinese investment in the port of Hamburg. On October 26, Scholz officially allowed the Chinese state-owned enterprise COSCO to buy a 25 percent stake in the port. The move has rankled allies both foreign and domestic, likely prompting his November 3 op-ed. He claimed the “yardstick” that Germany used was whether the investment “creates, or exacerbates, risky dependencies” on China.

While a 25 percent stake may not be a “dependency,” it does give China another foothold in a critical European port and helps advance Beijing’s strategic interests. The fact is that China does not need another port investment — it is already heavily invested in ports all over Europe — it wants another port investment. More ports mean more influence and a greater ability to project power abroad. Approving the investment in Hamburg’s port is yet another illustration of what results from a myopic conception of the Chinese threat.

Germany has made a lot of unexpected changes in 2022, so one can hold out hope that its China policy will be next. But if Scholz’s rhetoric is any indication, it doesn’t seem like a policy rethink is anywhere on the horizon. It is frustrating to watch as Germany is taught the same lesson over and over again.