Moscow

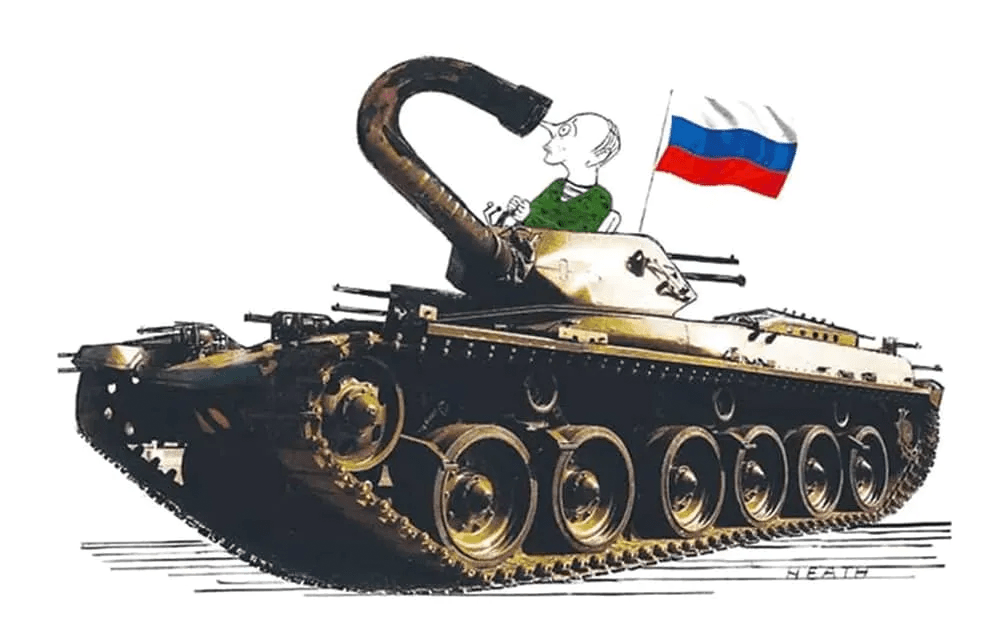

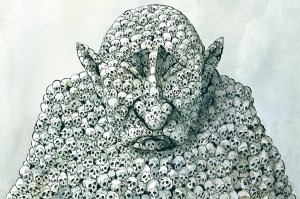

A week of somewhat mixed messages from the Kremlin. One day Vladimir Putin opened Europe’s largest Ferris wheel and presided over citywide celebrations of Moscow’s 875th anniversary, full of calm and good cheer and mentioning the war only in passing. A few days later he appeared on national TV telling the world that he was “not bluffing” about using nuclear weapons and announcing a partial mobilization. Putin has never fought a contested election in his life, so he’s never been a great one for the common touch. But in his latest address he looked as pale and dead-eyed as Nosferatu.

Russians know better than most that the more strenuously something is officially denied, the more likely it is to happen. Defense minister Sergei Shoigu appeared after Putin to explain that the call-up would apply only to 300,000 military reservists with combat experience. In practice the povestki — summonses to report at recruitment centers — rained down apparently randomly. The whole of one recently graduated class of young Moscow architects were called up on the grounds that they had completed some compulsory military training as part of their course. The fifty-five-year-old father of a schoolfriend of one of my neighbors received papers despite never having served. He went to the recruiting office to explain the mistake. Two hours later he was on a bus to a training camp.

In Russia, every crisis is also a business opportunity. Within a day of Putin’s mobilization call, reports a businesswoman friend, a network of consultants specializing in bronirovanie – literally, to “armor-plate” something — had sprung up. Because vaguely defined “specialists” are exempt from the draft, managers scramble to furnish employees with papers proving they are indispensable. Average cost: $130 per person, most of which gets kicked back to the draft offices issuing the exemptions. A widely accepted tariff for crossing the border without draft papers has also emerged: $330, in cash to border guards.

Pranksters posing as draft officers call Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov’s son, ordering him to report for a medical exam. “Obviously not!” thirty-two-year-old Nikolay Peskov replied. “You must understand it is not right for me to be there. I have to resolve this on a different level.” Key word: “Obviously.” The idea that the children of Russia’s elite would serve their country is, to them, a self-evident absurdity.

Signs of the times: “Will swap a Toyota Corolla for a one-way ticket to Istanbul,” write the parents of a desperate potential draftee on social media. In Moscow’s bus stops, the advertising gap left by the withdrawal of 1,200 foreign companies has been filled with patriotic posters. Some include Soviet-style caricatures of a top-hatted, malevolent Uncle Sam holding marionettes of Pippi Longstocking and a Moomintroll dressed in the colors of the Swedish and Finnish flag. “Don’t become puppets in strangers’ hands!” is the caption. It takes me a moment to register that the retro-style poster is not intended to be ironic.

On a recent visit to Kyiv I found the war all-pervasive, from the number of young men in uniform — even in hipster cafés — to the regular air-raid sirens. But to most Muscovites the war had been all but invisible before Putin’s mobilization announcement. Or at least, its consequences were no more than a mild irritation: no Apple Pay or Zoom, no software updates or international banking, McDonald’s and Starbucks replaced with lookalike local clones. But bars, restaurants and theaters were packed. Moscow supermarkets were stocked with every kind of foodstuff — including plenty of goods from sanctioned Europe. After this week’s mobilization, though, the war suddenly moved from being a distant and ignorable unpleasantness to something that was, to tens of millions of Russians with military-age male relatives, very up close and personal.

News breaks of three apparent explosions that ruptured Gazprom’s Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines, causing boiling half-mile-wide areas of turbulence as the 300 million cubic meters of gas in each pipeline — at £2 ($2.20) a cubic meter — bubbled uselessly to the surface. Swedish and Danish officials have been cautious about attributing blame. My Moscow acquaintances, less so. “Putin’s blowing everything up before he goes down,” one energy trader friend — once a passionate patriot, now a scared draft-dodger — asserted. In saner times, the Nord Stream pipelines were a way for the Kremlin to assert power over Europe. Putin’s cut-off of supplies through Nord Stream 1 in July to pressure the Europeans into dropping their support for Kyiv was the diplomatic equivalent of strapping on a suicide vest. But to his surprise and disappointment, Europe proved quick to move to liquefied gas alternatives. Was blowing up the Nord Stream pipelines the modern equivalent of Cortez burning his boats on the beach?

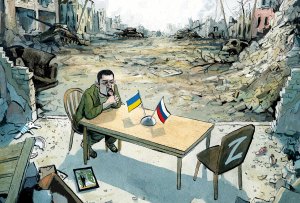

Moscow taxi drivers are in rare agreement. They’ll fight if Russia is attacked, but not “to take someone else’s house.” A week ago, Putin could have declared victory, proposed a peace plan and split Ukraine’s supporters. But with mobilization sparking protests in hitherto loyal places such as Dagestan, he’s made regime change a real possibility. I wrote in these pages a few weeks ago that the alternatives to Putin are unlikely to be better. As poet and critic Dmitry Bykov says, Putin is not Hitler, he’s Kaiser Wilhelm II. After military defeat in Ukraine comes a new version of Versailles, Weimar and then the real disaster. “I’m not afraid of a corrupt Russia,” Bykov says. “I’m afraid of a truly fascist Russia.”

The Ferris wheel that Putin opened broke down after two days, leaving its passengers stranded, trapped high and helpless in the thrill-machine they’d so trustingly boarded.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.