There is a joke in Taipei that if China invades Taiwan the best place to shelter is in microchip factories, the only places the People’s Liberation Army can’t afford to destroy. The country that controls advanced chips controls the future of technology — and Taiwan’s chip fabrication foundries (“fabs”) are the finest in the world. Successful reunification between the mainland and its renegade province would give China a virtual monopoly over the most advanced fabs. Given that Xi Jinping has made clear his intention to take control of Taiwan by 2032, it is no wonder that the American government is worried about the concentration of cutting-edge semiconductor technology on the island.

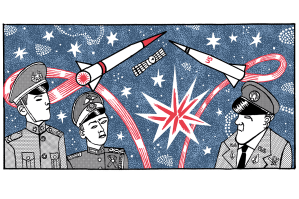

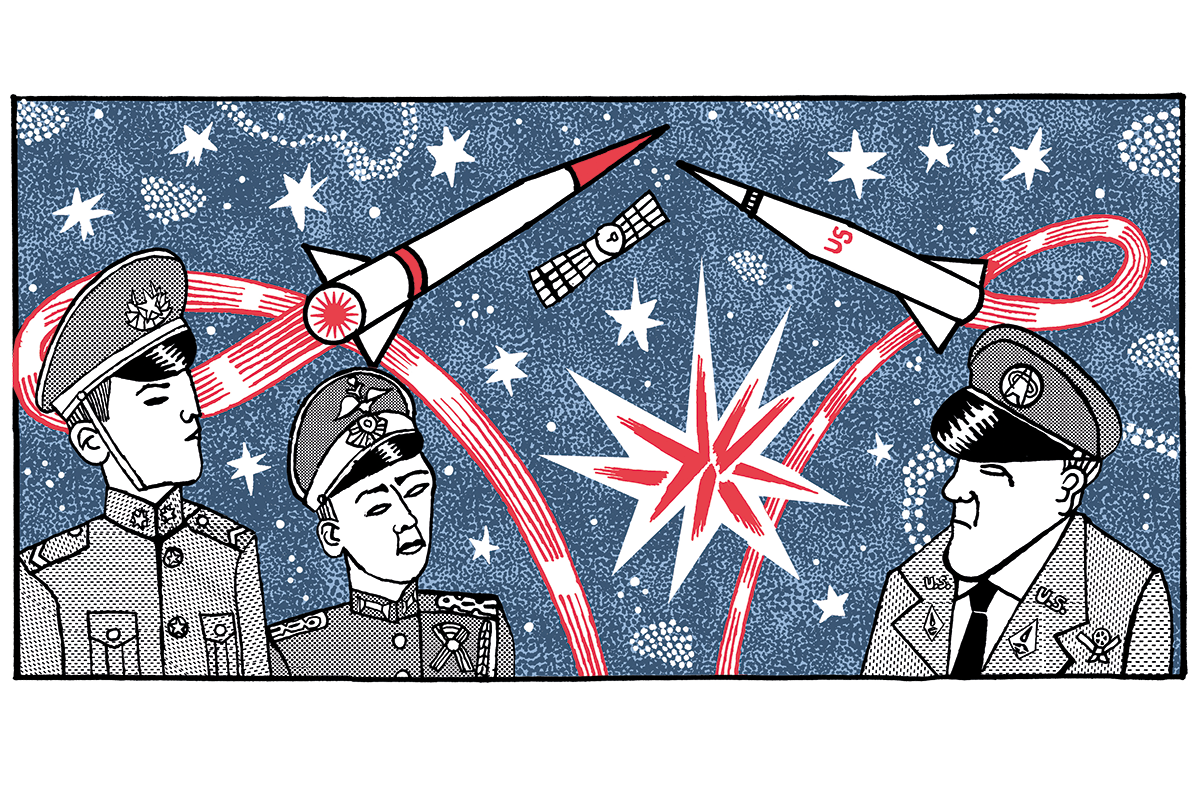

For this reason, in recent months the United States has taken various steps to limit China’s access to advanced semiconductors. These chips are the electronic-commodity equivalent of oil and gas, and the embargo is an act every bit as aggressive as the US ban on oil sales to Japan in 1941, at a time when 80 percent of Japan’s oil came from Standard Oil of California. That led directly to Emperor Hirohito’s assault on Pearl Harbor. One wonders where the current embargo of chip technology will lead.

The US attack on China’s bid to dominate future technology is twofold. The first part of the strategy is to rebuild America’s share of the semiconductor fab market, which fell from a peak of 37 percent in 1990 to just 12 percent in 2020. In August, Joe Biden signed a $100 billion Innovation and Competition Act to help finance technological research and the building of fabs in the United States.

It’s an attempt by the administration, supported by Republicans, to reverse the hollowing out of US manufacturing — a policy first identified and pursued by President Donald Trump. With bipartisan support, the new act specifically aims to punish US companies that invest in China.

Xi, clearly alarmed, has urged China to increase its technological self-reliance and to “accelerate the pace of legislation in the fields of digital economy, internet finance, artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing etc.” America’s aim of disrupting China’s technological advance is being strongly supported by a Western private sector that has become increasingly aware of the geopolitical risks of having such a high percentage of its chip capacity based in Taiwan.

Intel, the daddy of the semiconductor industry, which supplied Apple for fifteen years until 2020, is now in catch-up mode. In January, the company poached Apple’s director of Mac system architecture and announced plans to produce system chips to compete with Apple’s top-of-the-line M1 series. The intention is to regain Intel’s position as the world’s leading integrated design and fab company by 2025.

Intel’s battle is not just with Apple. It is also with the dominant fab business, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which has more than a 50 percent global share in the manufacture of advanced semiconductor chips and, even more importantly, a 92 percent share in the most advanced five-nanometer chips.

Under the leadership of its new CEO Pat Gelsinger, Intel is aiming to turn Intel Foundry Services into a $200 billion business aimed at building advanced computer chips. This is a market that the company left in the 1990s. As well as completing the building of a fab in Oregon, Intel is planning new ones in Arizona and Ohio. $80 billion is also earmarked for fabs in Europe with sites in Ireland, Germany and Italy being negotiated. It is a vast project, and some analysts doubt Intel’s ability to execute it.

But if the first part of the US scheme is to match or exceed China’s state-funded model for hi-tech industries, the second part is more nefarious. China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation is desperate to join the ranks of the advanced chip manufacturers: TSMC, Samsung and Intel. This ambition is supported and pushed by SMIC’s major shareholder, the Chinese government. America’s plan is to block China’s ability to import the machinery that enables the manufacture of advanced chips.

Key technologies for semiconductor manufacture include ultraclean rooms, deposition, coating, etching, ionization and packaging. But the ultimate determinant of advances is lithography — the fine printing of electronic circuits on to silicon wafers. The most advanced chips are currently printed at a gauge of just five nanometers: five thousandths of a micron or five billionths of a meter. (By way of comparison, the average human hair is seventy microns wide.)

At present there is only one company in the world that can make lithography machines that print wafers at the five-nanometer gauge. Based in a nondescript suburb of Eindhoven in the Netherlands, Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography is perhaps the world’s least well-known hi-tech business. Yet it ranks just behind Shell as the fourth-largest company in Europe.

ASML’s highest tech machines use a process called “extreme ultraviolet” lithogra- phy, which makes them the only systems that can do lithography below 13.5 nanometers. The company produces approximately fifty machines a year at $150 million a pop (plus service contract). As a result, it owns that rare commodity — a market monopoly.

In August, the United States successfully put pressure on the Dutch government to block the export of EUV machines to China. China is therefore stuck at 13.5-nanometer lithography. Furthermore, America is now applying pressure on ASML to stop the company exporting the previous generation of machines to China.

Will America succeed in its attempt to throttle China’s technological ambitions? At the moment there is no indication that any other company has the knowhow to duplicate ASML’s EUV machines. Not only do they require design expertise, their manufacture involves a complex web of hi-tech subcontractors worldwide; replicating that would be remarkably difficult. But perhaps the main barrier for competitors lies in the billions of lines of software code which seem to double every four years.

One assumes that Intel, which has a 15 percent stake in ASML, compared to TSMC’s 5 percent and Samsung’s 3 per cent, has a good idea of where lithography is headed as it contemplates an atomic-scale future. It has already placed a $300 million order for ASML’s next-generation angstrom-level machine for delivery in 2025.

As long as the Dutch play ball — and there is no reason to suppose they won’t — the United States is likely to defeat China in the “chip war,” at least in the short term. But there are caveats. For one thing, China has a window of opportunity to invade Taiwan and take control of TSMC’s chip foundries before the bulk of new fab foundries are transferred to America and Europe.

Second, China may develop lithography technologies of its own. Other technologies for atomic-scale lithography are being explored. China has already announced the development of a seven-nanometer chip using the last generation of lithography machines combined with various technological tricks, although experts doubt whether chips produced this way could be harvested at an economic level of yield.

America’s Semiconductor Industry Association has concluded that, for the time being, “more advanced technology is still out of [China’s] reach.” Nevertheless, China has demonstrable world-class scientific ability. Candidates to replace ASML’s EUV techniques include X-rays, electron beams, ion beams and nanoimprint lithography. China could get there first.

The possible unintended consequences of the chip war, and other technological wars, should be noted. If globalization has brought enormous economic benefits to the world since Deng Xiaoping’s deregulation of the Chinese economy in the 1980s, deglobalization, the retrenchment to national interest and autarky, is likely to bring the world slower growth, or worse. Both America and China will be losers in their chip war even if the end result is not a real global war.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.