Many years ago, when I mistakenly thought that I stood a chance of embarking on a career in publishing, I went for an interview at an independent publisher to be editorial assistant and all-around dogsbody. I remember the interview well, because it was the shortest I ever had. The first question was, “How do you like to be managed?” I replied, “sternly, with a large whip.” The second was “What would your ideal role in publishing be?” and I answered, “running Jonathan Cape in the Eighties.” It became clear that our paths were not to join, and I left the room with thanks and smiles. I don’t believe that I was ever actually rejected for the job.

Circus of Dreams, the critic and journalist John Walsh’s rambunctious and hugely entertaining history of the British literary scene in the 1980s, summons up something of the excitement, and the absurdity, of the period. Walsh, who was literary editor of the Sunday Times of London under Spectator chairman Andrew Neil for some of the period described, had, in his words, “a ringside seat” to watch the evolution of publishing during that decade.

At the Eighties’ beginning, literature in Britain was in a moribund state. Although there were some excellent writers, not least Kingsley and Martin Amis, as well as their friends Philip Larkin and Anthony Burgess — women had less of a foothold — the sense remained that writers were a detached, unaccountable bunch, members of an exclusive (usually Oxford- or Cambridge-educated) club who did nothing so vulgar as publicly discuss or inscribe their work. But sales were declining; one mournful 1983 profile in the Sunday Times noted how various up-and-coming writers were forced to sell their houses and live off their partners to survive. As Walsh notes, “when it came to lucrative ways of making a living, [the article] made novel-writing sound barely a step up from taking in washing.”

Walsh juxtaposes the rise of such internationally successful, genre-bending (and blending) authors as Salman Rushdie, Julian Barnes and William Boyd with his own story. In less certain hands, this might make for smugness or arrogance, but Walsh brings near-heroic (or delusional) levels of self-deprecation to his tale. After a distinguished academic career at Oxford and University College Dublin, where he studied the late prose of Samuel Beckett, he changed industries and became a junior jack-of-all-trades at the publishing house Gollancz, where he was swiftly taken to task for his inappropriate nonchalance around the office.

His superior remonstrated with him for excessive informality — “only yesterday, downstairs, you said to me ‘How’s it going, old bean’” — and Walsh soon moved on to a business-focused magazine, the Director, which would have been an excellent position were it not for the fact that, by his own admission, Walsh knew absolutely nothing about the workings of the business world. (“I made elementary moves to familiarize myself… [but] I began to wonder if I had made a grotesque blunder.”)

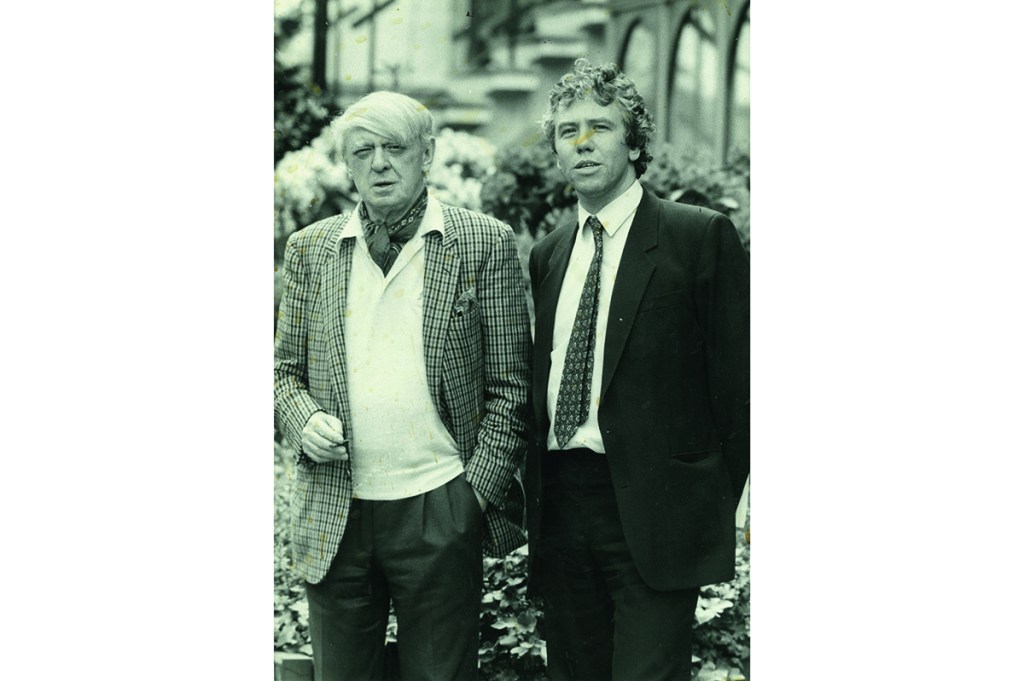

Our narrator, however, is not to be cowed. Instead, by the end of the third chapter, Walsh has announced that his grand ambition is to become literary editor of the Times by the age of thirty-five, which gets a big laugh. Up to this point, the would-be man of letters has presented himself as somewhere between unworldly and hopeless, grandly informing an incredulous Martin Amis that he is too busy to reread his 1981 novel Other People in order to make sense of the ending and smirking in delight while conducting his first interview — with the humorous writer Professor C. Northcote Parkinson — only to be upbraided for what his subject sees as excessive levity. It is unsurprising that when he repeats his world-conquering plans to the novelist William Trevor and his wife Jane, he is not greeted with the chorus of approval that he expects. Trevor murmurs “noncommittally” and Jane brightly says, “That’s the spirit. I’m sure you will.” Walsh notes, “Had she not been across the table from me, I’m sure she’d have patted my hand.”

Even allowing for exaggeration from this talented Anglo-Irishman, it seems extraordinary that he could storm the citadel of literary journalism in the way that he did: first as books editor of the London Evening Standard, and then as literary editor of one of Britain’s most prestigious newspapers. After all, he hadn’t been to the right school (read: old and fee-paying) and he refused to be modest about his abilities. Perhaps interestingly, the British reviews of his memoir have been less warm than might have been anticipated; there has been the sense of some residual grudges being settled.

Walsh was not just helped by his obvious intelligence and charm, but also by the sea change taking place in contemporary publishing. Younger, more experimental writers were taking over from the ancien régime, and editors and publishers were becoming similarly daring. Once-conservative publishing houses were now run by men and women who were seen drinking and, on occasion, fornicating with their colleagues and authors in members’ clubs. British fiction moved away from realism into new areas of philosophical, fantastical and social territory. A new chain of bookshops, Waterstones, opened, which did away with the formal and old-fashioned tenets of bookselling and were youthful and fashionable in their approach. Literary festivals began, most notably in Hay-on-Wye in Wales, and authors were encouraged (sometimes to their chagrin) to appear in public, to sign copies of their work and to discuss their writing.

This is a book focused on British, rather than American, publishing — which had undergone its own sea change decades before, with the emergence of Roth, Updike, Heller and the like — but there are many amusing anecdotes about writers from the United States. Walsh describes how Noam Chomsky, Gore Vidal and Edward Said visited Waterstones to sign books, “like gods descending from Olympus,” with a mixture of curiosity and excitement, and there is the treasurable anecdote of how, as Sunday Times literary editor, Walsh attempted to sign up Norman Mailer to review Salman Rushdie’s first post-Satanic Verses novel, Haroun and the Sea of Stories.

When Neil asked Walsh how much Mailer would be charging, Walsh blithely replied, “His agent says they’ll want ten thousand dollars.” As Neil “faintly” repeats, “Ten grand for a children’s book review,” Walsh attempts to argue for its inclusion, but is firmly put in his place. “I was going to upbraid Andrew for stifling a valuable contribution to the Rushdie debate when I suddenly remembered I had an urgent lunch appointment in the canteen.”

This is an enjoyably good-natured book, largely without point-scoring at the expense of writers living or dead. It skillfully gives the impression of candor and insider knowledge without saying anything devastating, although an explicit anecdote about the author Frank Delaney seducing Princess Margaret includes some eyebrow-raising details that I was surprised made it into the final draft. But Walsh eventually left the Sunday Times to go and work on the Independent newspaper, which is itself no more, and the book’s “Afterwords” has the air of an epitaph for a bygone age of publishing. Walsh rouses himself to attack Sally Rooney and her type (“Normal People is a blandly written, linguistically unadventurous Young Adult novel of schoolgirl romance, with more sex than is common in the genre”) as well as contemporary publishing in general.

Although his remarks about how “modern novels need to have ‘relevance,’ ‘relatability’ and even basic ‘acceptability’ to succeed” and how “in the 2020s, male writers are told that nobody wants to hear their stories, and commissioning editors in modern publishers are advised not to take on books that won’t sell until they’re part of an acceptable demographic” specifically refer to British publishing, they are no less true of the American literary industry. Walsh refers to the contemporary landscape of books now seeming like “a very bleak place,” which few would argue with.

It is this sudden, although understandable, shift from lighthearted and often very funny reminiscence to mournful consideration of how hopeless the not-so-brave new world of books has become that gives Circus of Dreams its center of gravity. Perhaps some readers will remain optimistic that we might emerge out of the darkness and into a similarly enlightened 2030s. But we cannot count on it, alas.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2022 World edition.