In late March, roughly a month into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, an unnamed NATO official told NBC News that the conflict was turning into a meat grinder for both sides. “If we’re not in a stalemate, we are rapidly approaching one,” the NATO official said at the time. “The reality is that neither side has a superiority over the other.”

Sure enough, a month and a half later, the Pentagon’s top intelligence official testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that “stalemate” is exactly what is occurring. “The Russians aren’t winning, and the Ukrainians aren’t winning, and we’re at a bit of a stalemate here,” Lieutenant General Scott Berrier, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, said on May 10.

That assessment continues to hold two weeks later, as the battlefield in Ukraine’s Donbas region comes to resemble a bloody seesaw. The Russians spend a day acquiring one kilometer of ground, only for the Ukrainians to counterattack shortly thereafter. Maps dividing which party controls what territory often look identical by the week — if there are changes, it takes a microscope to spot them.

Now in its fourth month, the war is a slog on both sides. According to a recent British Defense Ministry intelligence assessment, the Russians have lost as many soldiers in Ukraine over the last three months as the Soviet Union lost in Afghanistan in nine years — about 15,000 personnel.

While we don’t know how many soldiers Ukraine has lost in the fighting, we can say with certainty that Russia’s bombardment has left the country in ruins. Mariupol, once a city of nearly half a million people, is a pile of debris and ash. In Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest metropolis, around 25 percent of the buildings have been destroyed. The Ukrainian government is calculating an astounding $600 billion in infrastructure damage so far. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky says as many as 100 Ukrainian troops could be dying in combat every day. At the time of writing, Ukrainian forces holed up in Severodonetsk, a mid-sized Donbas city of 100,000, are vastly outgunned by Russian artillery lobbing explosives at an unlimited list of targets.

Ideally, a painful stalemate like this can, over time, pressure the combatants into exploring peace talks. But the key phrase there is “over time.” The three months of war have taken an unquestionable toll on Ukraine’s civilian population (as many as 20,000 civilians may have died in Russia’s siege of Mariupol), but there remains a euphoric feeling among the Ukrainian people that military victory over the Russian occupiers is still a possibility.

There is now deep resentment, if not hatred, across Ukraine’s eastern regions (even amidst Russian-speaking Ukrainians) of Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin. This resentment adds fuel to the Ukrainian political elite’s more uncompromising position about what is and isn’t acceptable vis-a-vis a peace settlement.

While Zelensky recognizes that the war will only end “through diplomacy,” he is on record opposing any territorial concessions to Moscow in order to end it. Indeed, hours after Zelensky made a reference to diplomacy, his chief negotiator rejected the notion that ceding territory was an option and even questioned whether handing over the Donbas to Putin would be enough of an incentive for the Russian president to call his troops back. There is a strong feeling within the Ukrainian government that territorial concessions will simply whet Putin’s appetite for land. It’s a hypothesis that pundits in the West, the Atlantic’s Anne Applebaum especially, have used to support their argument that nothing short of a full victory for Kyiv is appropriate.

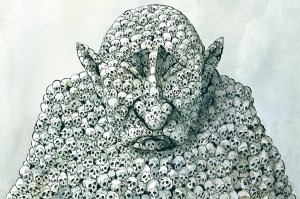

That argument is popular inside the Washington Beltway, feeding the narrative of a morality play, where the good and righteous David slays the evil and bloodthirsty Goliath. In the context of Ukraine’s war, however, Goliath still has a lot of firepower at his disposal, is willing to use that firepower recklessly, and is as convinced of its ability to succeed as Ukraine is convinced of its ability to resist.

Putin could have used his Victory Day speech earlier this month to throw out a diplomatic olive branch. The fact that he didn’t do so speaks volumes, not only about his stubbornness and the insularity of his inner-circle, but also about his mindset — losing, or even the appearance of losing, is unacceptable and won’t be tolerated. By making the invasion the cornerstone of his two-decade legacy as Russia’s leader, Putin has cornered himself like a crazed cat, where clawing his way out is the only thing standing in the way of being caught. And the more insistent Kyiv is about a military victory, the more desperate Putin will be to fight as hard as he can to avoid a defeat.

Wars end in one of two ways: one side overpowers the other, or the battlefield becomes so fruitless and costly that the combatants decide to sit down and end it through a negotiation. Alternatively, you could have a frozen conflict, where the parties learn to live with the facts on the ground even as they stonewall each other (think Transnistria, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and Nagorno-Karabakh and the Donbas between 2014 and February 2022).

Ukraine’s story is still unwritten. But as the war settles into a familiar pattern and both sides continue to treat diplomacy as a chore best left to some later date, the frozen conflict route is looking like the best of bad options.