New York’s Upper East Side — 1018 Madison Avenue, to be exact — currently hosts another world at the Gray Gallery. It’s a universe with a near-scientific attention to detail. Plant stems are bisected and, in turn, bisect paintings like winding snakes; petals and branches are painted in such microscopic detail that they appear like the surface of some far-flung planet; and canvases are awash with such bright, clean lines they seem almost like subway maps of a particularly topsy-turvy city.

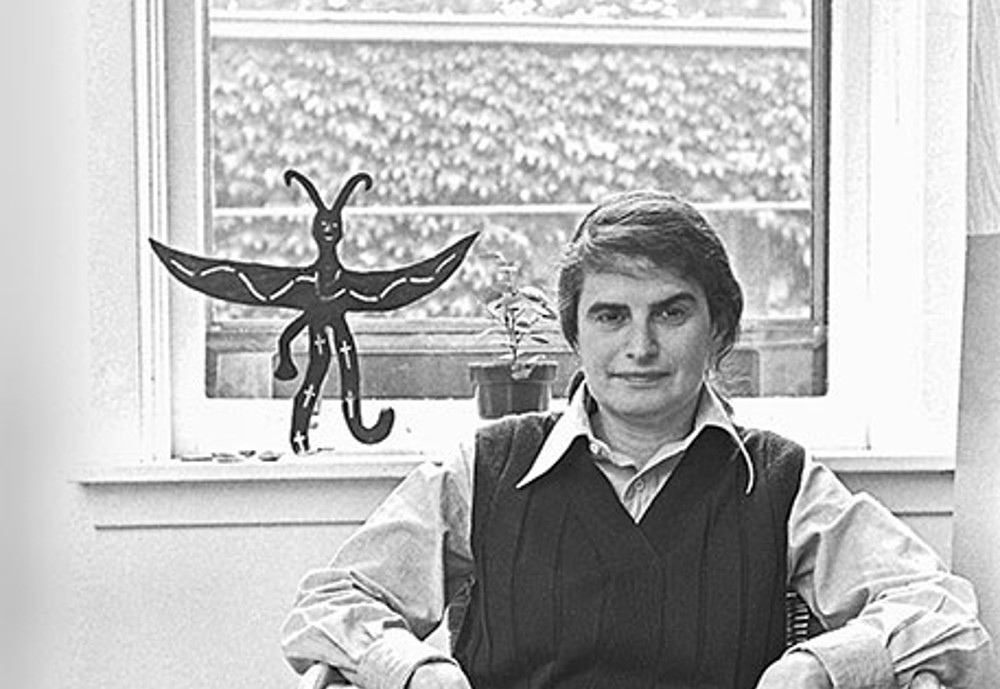

The works — pastels, oil on canvas, and oil on linen — are those of Evelyn Statsinger (1927 – 2016), the deeply underappreciated artist who lived in New York, Chicago, and Michigan. The works in this exhibition at Gray New York, curated by Dan Nadel, are from the 1980s and ’90s, when Statsinger was living in an old schoolhouse in Allegan, rural Michigan.

After a stint at the famous School of the Art Institute (she graduated in 1949 and had her first solo show just a few years later), Statsinger was momentarily aligned with the Chicago “Monster Roster” movement. This was itself a response, in kind, to the abstract expressionism of New York in the mid-twentieth century. Leading figures of the movement, such as Leon Golub, painted what became known in art criticism as the “Chicago Idiom” — drenched in dark, brooding, post-war anguish.

Statsinger wielded her paint in the opposite direction. If her early works were imbued with dark, quiet intensity, the art in this show is the near-opposite. There is still intense feeling, and perhaps quiet — they demand their viewers’ whole, unchattering focus — but dark they most certainly are not.

Statsinger takes the forms and symbols of the natural world around her — from branches in Sassacricket High (1987) to the botanical forms of stamens and petals in Shore Line Drive (1998) — and enlarges them until they almost, but not wholly, lose sight of their initial referents. In his essay for the exhibition, curator Nadel remarks that Statsinger found her images by “arraying her vocabulary of marks and forms — tonal clouds, buttercups, threads, stems, fossils, shells, husks, ripples — but never in a way that any of these things become individually identifiable.”

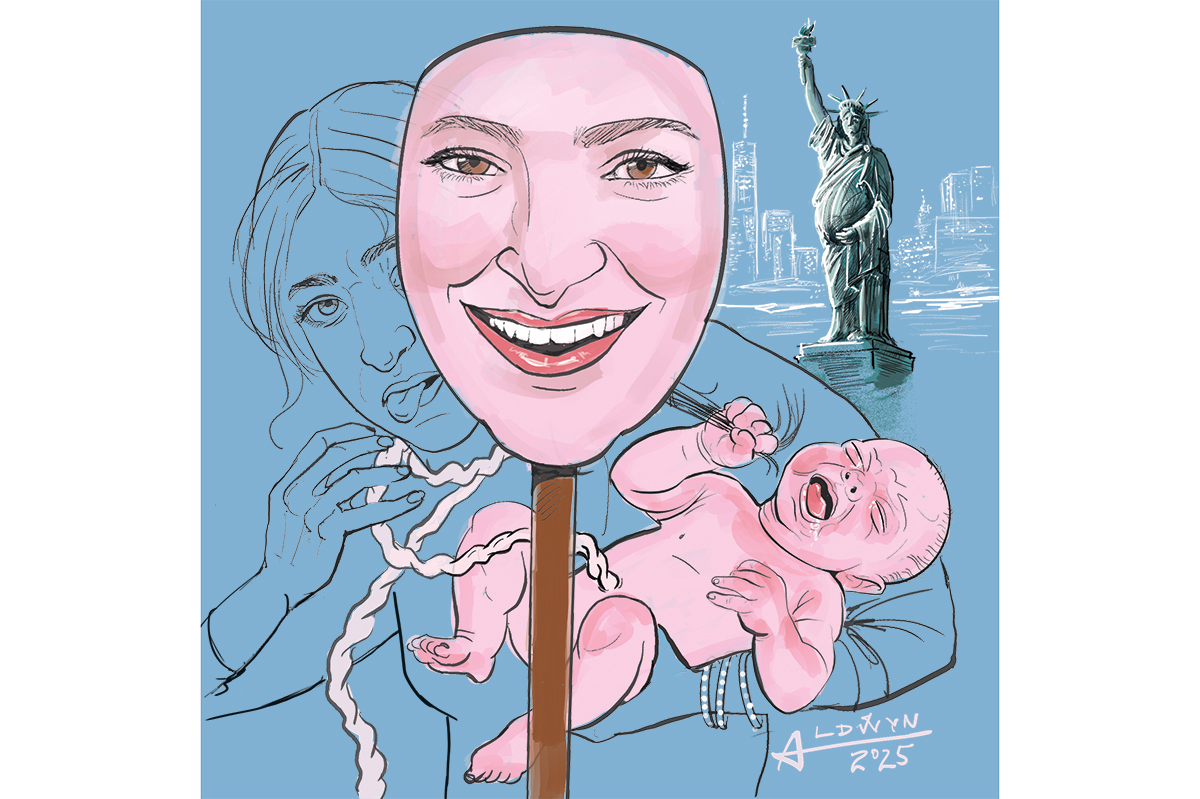

Statsinger is not a particularly well-known figure in the art world: she is not tied to one movement, nor is it easy to place her within one school. As Nadel notes, she could not have avoided a brush with Surrealism: “Chicago was practically suffused with it, after all.” But she was not surrealist in the way that, say, the imagists like Barbara Rossi were. Nor are her works as wholly abstract as the work of her contemporary, the Japanese American artist Miyoko Ito.

There is something akin to Georgia O’Keefe’s flower and shell paintings in Statsinger’s repeated attention to natural forms — and even a hint of O’Keefe’s Texas landscapes, too. The repeated dot and line motifs that make up so many of the paintings and pastels are also reminiscent of some Aboriginal art. The longer I stare at Statsinger’s kaleidoscopic patterns of dots and lines, the more I wonder if the artist had known Australian Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s large “dots within dots” canvases.

Katy Hessel, host of The Great Women Artist’s podcast and author of the forthcoming book The Story of Art Without Men, notes the illusive and allusive qualities of Statsinger’s work. Hessel finds Statsinger’s paintings “utterly transfixing” and sees them as belonging to an “interesting dialogue with women artists working in the twentieth century, such as Gertrude Abercrombie, Belkis Ayón, and Agnes Pelton, whose works — dealing with contemporary subjects of surrealism, ecology, and spiritualism — are only just coming to mainstream attention and acclaim.”

This link to Gertrude Abercrombie is particularly fascinating. Abercrombie’s paintings are different from Statsinger’s: they exist on a far smaller, spookier scale of Surrealist landscapes, women in billowing dresses, and ever-menacing cats. But Abercrombie’s life was very different from Statsinger’s: she was the doyenne of the bohemian Chicago jazz scene whilst Statsinger was just a student. But not only were both Chicago artists working with an artistic language delicately balanced between representation and abstraction, both have — since their deaths — been curated in exhibitions by Dan Nadel.

Nadel held an exhibition of Abercrombie’s work in 2018, the first in New York since 1952. The exhibition — and accompanying essay by Robert Storr — brought Abercrombie’s works (which Storr so evocatively describes as “a dreamland of gnawing disquiet in a region of unchanging plainness and austerity) out of the half-light of her “grisaille twilight palette.” If not a household name, she is now, deservedly, a better-known one.

Statsinger did not lack for fame or prestige during her lifetime. She exhibited with the Art Institute of Chicago in 1957, the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1954, and many other galleries in the Midwest and across the US. She had a connection to the Chicago-based women’s art collective Artemisia and was even profiled in Time. The journalist, sadly, couldn’t avoid the clichés about female artists: she was, apparently, “pretty, proud and painfully shy.”

Statsinger died in 2016. Just the year previously, the Gray Gallery had held an exhibition of her work spanning sixty years. This current collection and catalogue, despite — or perhaps, because of — its narrower focus, is no less impressive. Voyage to the Upper East Side, bask in Statsinger’s extraterrestrial worlds, and be prepared to tell the world about them on your return.