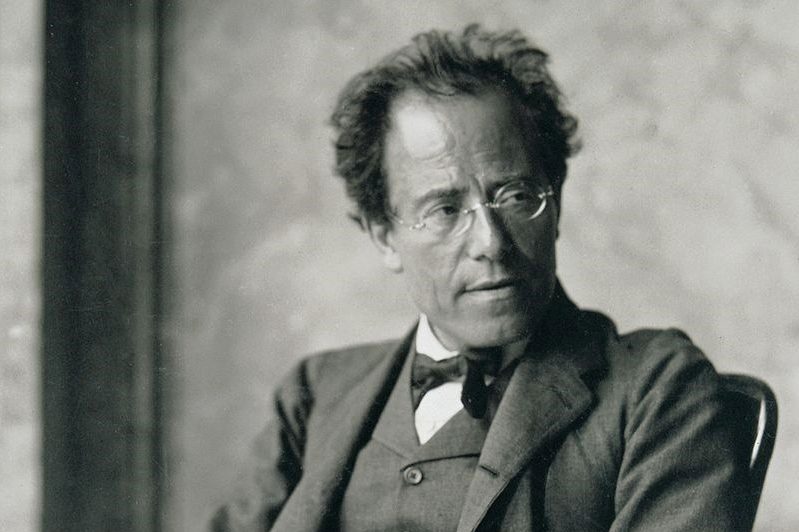

On February 23, 1897 a slight Austrian eccentric walked into the parish church of St. Ansgar and St. Bernhard in Hamburg, affirmed his belief in the Holy Trinity, the one, holy, Catholic, and apostolic church, and received the sacrament of baptism. Some months later, Gustav Mahler was named principal director of the Viennese court opera — a post that would have been denied to him had he not converted from Judaism. One hundred and twenty-five years after his baptism, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts honored Mahler by performing his Second Symphony with legendary guest conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. The “Resurrection Symphony,” as it is called, is beloved by brass players for its marathon fortissimos and, after the audience is lulled to peace by the strings, a pay-off of live thunder written into the fifth movement.

“He was the last great composer of symphonies. The first time I heard Mahler Two I said to myself, ‘this is what I want to do with my life,’” says Tom Cupples, the National Symphony Orchestra’s second trumpet. He should be in his tails under the lights, but he is sitting in the nosebleeds, acting as Virgil for an uncultured scribe whose notebook crinkles as he scribbles nonsense like “fortissimo(?)” and “pay-off of live thunder” while asking what movement we are on.

Navigating a symphony with a noisy journalist who has been drinking rye is frustrating enough, but that is the least of Cupples’s concerns. He has been suspended without pay since November 30 for refusing a Covid-19 vaccine after the Kennedy Center rejected his religious exemption request. The orchestra insists that Cupples and three other suspended musicians pose a mortal threat to the ninety-two musicians onstage who are apparently inoculated against the disease. Many have contracted the coronavirus in Cupples’s absence, but that has not shaken management’s confidence about the true source of the threat.

Unlike Mahler’s, nobody can doubt the sincerity of Cupples’s conversion to Catholicism. In the weeks leading up to his reception into the church on Easter 2019, he wouldn’t shut up about it. A few years later, management feigned surprise when he proactively asked for a religious exemption from forthcoming mandates. HR grilled him over the sincerity of his faith. It dismissed a supportive letter written by Cupples’s parish priest, asking pointed questions that cited other church officials who have supported the vaccine. Ultimately, management dropped the question of faith altogether and denied the request on October 25, 2021, saying Cupples “would impair workplace safety.” In December the center abandoned previous testing regimens that had allowed Cupples and his colleagues to perform during the NSO’s abbreviated return to work.

“They say they are following the science, but they have routinely moved the goalposts. We’ve blown past the 80 percent threshold of vaxxed performers that was previously the target. There are only four of us — how could we be a danger to all of these vaccinated people?” Cupples says. “It is just plain discrimination.”

Religious exemptions have come under the microscope across society since policymakers turned to mandates in an effort to coerce those hesitant to take mRNA vaccines. The armed forces have famously denied every conscience-based exemption request and are in the process of discharging thousands of believers who take issue with vaccine mandates. The Supreme Court has rejected religious challenges to state vaccine mandates for healthcare workers in Maine and New York, though it did strike down the Biden administration’s attempt to force large employers to implement such requirements. Cupples turned to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for relief, hoping to avoid a costly and lengthy federal lawsuit. His complaint of religious discrimination is being investigated by the agency, which does not comment on pending cases. Cupples says the EEOC ruling will not only give him grounds to recover his lost wages but send a message to employers that disregard conscience rights for their workers.

It is a testament to Washington’s imperviousness to taste that its cultural epicenter is housed in the ugliest building in the city. The Kennedy Center looms over the Potomac with all the charm of a container ship. On our April visit, Cupples approaches the entrance with the confidence of a Somali pirate and is immediately approached by a security guard. Rather than chastising our affront to the Center’s Covid policies, the guard flashes a wide grin and says, “It’s been too long.” He and Cupples are still hamming it up when two women in black appear and greet the rogue musician with hugs. One of the women, an NSO harpist, excuses herself to go backstage.

We submit our negative tests and proceed to the bar, then to the back patio overlooking the river; even here, many of the attendees remain masked. There we marvel at the John F. Kennedy quote etched in marble, the one that says a “fascinating challenge” of our day is “to further the appreciation of culture among all the people, to increase respect for the creative individual, to widen participation by all the processes and fulfillments of art.” An unmasked man with a cardigan and a cane eavesdrops as Cupples explains to me what Mahler means to a brass player. The man explains that he is something of a cornet player himself and is looking for a knowledgeable musician to teach his grandson. His eyes light up when Cupples reveals his pedigree and describes his predicament.

“I’m a retired physician, and it is nonsense!” the man says. His masked date interrupts what was shaping up to be a lively monologue. They must get inside; their daughter is playing the harp tonight.

The old man may not be the only unmasked person wandering the grounds of the Kennedy Center. Thomas, the guest conductor, has also shirked a mask during what will surely be his last run with the NSO — he’s been given a brain cancer diagnosis so Covid probably doesn’t seem especially scary. Days before the Mahler performance, management informed musicians that HR had waived masking protocols especially for Thomas. No reason was provided — and Thomas did not respond to request for comment.

A Kennedy Center spokeswoman declined to address the conductor’s exemptions or the EEOC suit, citing confidentiality. “We look at every individual situation and apply the same standards for considering accommodations,” she says.

Cupples can’t help but laugh at the situation. It is just the sort of double standard that prompted Brooklyn Nets star Kyrie Irving to buy courtside seats to a game he was legally barred from playing in thanks to New York City’s vaccine mandate for workers. The city lifted the rule for basketball players within weeks of the publicity stunt/protest.

Cupples dismisses the comparison. He has too much riding on the EEOC complaint to afford spectacle. He put his suburban Virginia house on the market in April out of his distrust that his employer or policymakers would do anything to protect religious freedom. He does not want to jeopardize the investigation, nor does he want to undermine his union’s effort to bring him and his colleagues back to work. He insists his presence at the symphony is purely out of love of Mahler.

“Mahler wrote for God, not for the faculty lounge. It is pure beauty,” Cupples says as the lights dim. The chorus sits peering ominously down on the stage. They are masked, stone-faced and silent, which will make it all the more jarring when they come in an hour into the performance. Their hands are folded just-so in their laps, unlike Tom, who is flipping his back and forth, serving as the guest conductor of the balcony.

Cupples’s dedication to his craft and his innocuous-seeming rhetoric immediately trigger my journalistic instincts, wired to sniff out when someone is putting on a show with a reporter present. The trumpet player is a self-described Jersey-born redneck built like an offensive lineman. I begin peppering my notebook with big block letters insulting Tom and all he holds dear and hold it in his line of vision. He is too rapt to notice. This giant man appears to have tears in his eyes by the fourth movement, when the brass section really shines through. “Here comes God,” he murmurs, and I don’t think it was directed to me.

There is a minutes-long ovation, curtain down, and we are off to the Watergate where musicians and classical music groupies flock after shows. Cupples is greeted like a beloved uncle, rather than the unpopular gadfly he has always been among his colleagues. The Kennedy Center says these players risk bodily harm if they stand too close to this giant unvaxxed menace on stage, but the musicians can’t keep their mitts off him. He is the toast of the party, even hailed as a peacemaker for stopping a no-name journalist — who brought that guy? — from getting into a fistfight with the NSO tubist over the hazards of second-hand smoke outdoors.

“I didn’t pay for a drink all night. I’m shocked they were all so welcoming, but it goes to show that an orchestra is like one big dysfunctional family,” Cupples says.

Days after Mahler’s “Resurrection” wraps, Cupples gets a note from the union. The Kennedy Center’s forthcoming protocols will allow the unvaccinated to return to work by April 11. The proposal — which the spokeswoman declined to comment on — made no mention of back pay, and it will rely on community case levels as a benchmark moving forward.

In some of his letters, Mahler mentioned the nineteenth-century Jewish-born German poet Heinrich Heine as an influence. Heine (who became a Lutheran in his twenties) is remembered in cultural circles for declaring the “certificate of baptism… the ticket of admission to modern culture.” Cupples — who is convinced of Mahler’s genuine conversion — says he is fighting against the same coercive cultural forces today. “I’m going forward with the EEOC complaint regardless. It’s been a gut-wrenching eight months,” he says.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.