Among the many Russians who have protested against the war in Ukraine was twenty-six-year-old Muscovite Aleksandra Kaluzhskikh, who was arrested earlier this month. She managed to record her interrogation while she was being beaten and sexually humiliated by police shouting expletives. “Look at the schmuck,” one of her interrogators said, as Kaluzhskikh sighed and sobbed. “A marginal. What, you think they’ll do something to us for this [beating her]? Putin told us: kill them… That’s it! Putin is on our side. You are enemies of Russia. You are enemies of the people. I can kill you, and that’s it. And that’ll do it. They’ll give us a bonus for it.”

As I listened to this appalling eleven-minute recording, I thought of precedents. We have seen this before: these brutal interrogations, this cynical arrogance of power, this impunity. The rhetoric — “enemies of the people” — is a throwback to the 1930s under Joseph Stalin. Putin’s Russia is not Stalin’s USSR but there is an uncanny resemblance that makes you wonder whether the past has really crept back in, that it is merely waiting to reassert itself with renewed ferocity.

Nearly 700,000 people were executed in the USSR in 1937-38 during Stalin’s Great Purge. This was neither the beginning nor the end of violence. The Soviet system was built on repression, which was merely dialed up or down to suit the Kremlin’s purposes. Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD, resorted to torture to force confessions. Those who were spared death were sentenced to long prison terms in accordance with the infamous Article 58 of the Soviet criminal law, and then sent to the sprawling slave labor camp — the Gulag — where more than a million perished from hunger, disease and overwork. In the 1950s, Stalin’s successors launched a half-hearted effort to rehabilitate the victims of unjust prosecution. Survivors returned from the wilderness and tried to forget. There was a collective amnesia — and no reckoning, then or ever.

Archives of repression are still largely closed in Russia. But they were opened up in Ukraine, giving researchers an opportunity to take a look at the internal workings of Stalin’s hideous “meat grinder.” Consider the testimony of one Ignatenko, an NKVD executioner from Zhytomyr (just west of Kyiv). “You stand in blood and filth up to your knees all night,” he recalled some years later. “I nearly declared a strike, asking for rest.”

Ignatenko recounted how the detainees would be murdered one by one in the prison basement. Young women were stripped naked first. Sometimes raped. Then shot. And buried in unmarked graves. Those with any valuables would see them looted by the NKVD guards. Even golden teeth were stolen, knocked out with the revolver handles. Ignatenko’s account was one man’s experience, but it was repeated countless times across the Soviet Union. Very few of these murderers were brought to justice. Stalin was on their side. They were in the business of killing “the enemies of the people.”

How long does it take to turn a man into a beast? This rhetorical question acquired practical significance for me on one day in August 2019. I was in Moscow, taking part in large-scale protests against electoral fraud. These were ghastly affairs. The authorities mobilized the riot police. The policemen, dressed in black uniforms and wearing reinforced helmets with visors — for this reason, they were unflatteringly called “cosmonauts” — descended on protesters with batons, beating and kicking them, dragging them to police vans to cries of “shame!” A man in front of me, waving the Russian flag, was pulled to the ground. The tricolor was yanked from his hands and thrown into the dirt. He was beaten before being led away.

At thirty-nine, I was really an old man there. These were youngsters on both sides: those protesting peacefully, and those violently beating them. How did we get here? I took an easy way out, slipping away into a side street. Many did not even dare to join the protests. There were a few thousand people on the streets that day. The vast majority stayed at home, thinking perhaps that none of this concerned them personally.

In retrospect, 2019 was a good year. There was a whiff of repression in the air in Russia but there was still scope for protest. Leaders of the Russian opposition were incessantly harassed; some were already being arrested. But it seemed like there was still at least the potential for turning back, for halting Russia’s backsliding to authoritarianism. Hopes, such as there still were, were dashed in 2020, when Putin pushed through a constitutional referendum that would allow him to be re-elected to the presidency. Putin was here to stay, and things were about to get much worse. We soon discovered just how much worse when Alexei Navalny was poisoned with Novichok in August that year.

Navalny’s return to Russia after his treatment in Germany struck many as a heroic, even a foolhardy, act. Then came his arrest, and more public protest. There was one particular episode in St. Petersburg that attracted much public attention: a riot policeman was seen kicking a woman, Margarita Yudina, in the stomach. She ended up in the hospital, where the “cosmonaut” later brought her flowers and apologized. These “cosmonauts” have mothers, too, I thought: could they bear to see their mothers kicked in the stomach? Surely each of them must struggle with his conscience at least a bit. Even the NKVD executioner Ignatenko from Zhytomyr was not completely deaf to pangs of conscience. “You walk down the street,” he recalled. “And then you start running. You feel like you are being chased by those you killed.”

But how great is the distance between kicking an elderly woman in the stomach and killing her in the basement? Perhaps not as great as it seems. “I can kill you, and that’s it,” the unknown policeman beating Aleksandra Kaluzhskikh said. “They’ll give us a bonus for it.”

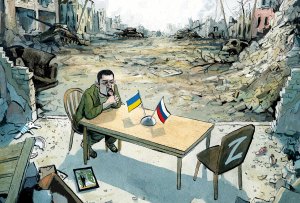

The war has given Putin a reason to clamp down even further on domestic dissent. Foreign journalists have been chased out of the country. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter have now been blocked. The Russian parliament has passed laws that make it punishable by fifteen years in prison to spread “fake” information about Russia’s war in Ukraine. Calls for sanctions against Russia are punishable by three years in prison. It is not even allowed to call it a “war.” This makes it all the more admirable that thousands of Russians have taken to the streets to protest the invasion of Ukraine since the war started, resulting in nearly 15,000 people being detained for ‘unsanctioned demonstrations’ in 112 cities across the country. The weekend of March 12 and 13 saw footage surface of officers using truncheons and stun guns to stamp out protesters. Meanwhile, in Nizhny Novgorod, a brave woman was arrested simply for holding up a completely blank sign. Then on the evening of March 14, Marina Ovsyannikova, an editor at Russia’s state-owned Channel One, interrupted a news broadcast by running into the studio with a poster that read: “Stop the war. Don’t believe in propaganda. They are lying to you.” She was immediately led away. The arbitrary nature of Russia’s legal system makes it unclear what will happen to Ovsyannikova, but if Russia’s new draconian laws are strictly applied, she could face years in prison. Indeed, these hastily adopted laws are strikingly similar to Article 58 of the Soviet criminal code, which saw so many murdered and enslaved. The reality of 1937-38 is not quite here yet but the legal basis for brutal repression is in place.

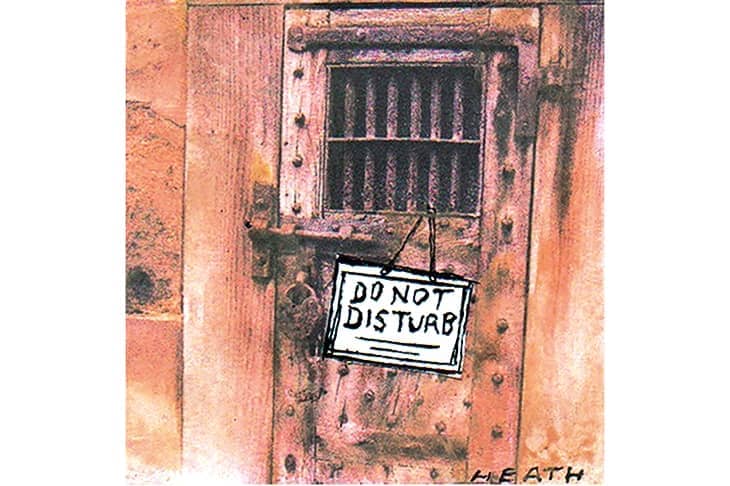

Kaluzhskikh, Ovsyannikova, and others like them knew what they would face when they voiced their opposition to the war. Many brave Russians — an unfortunately dwindling number — still have the guts to resist. And they do, despite being so brutally detained, beaten and humiliated. But the vast majority have been cowed into silence. A growing crowd of cheerleaders enthusiastically welcome the repression. It already feels like we are going down that murky stairway into the prison basement, brushing the dirty walls with bloodstains. There is something slippery and filthy underfoot. There is a cellar with a blinking lightbulb at the bottom of the stairs. And the NKVD’s Ignatenko is sitting there on a broken chair, revolver in hand, grinning. “Hi there. I knew you’d come back.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.