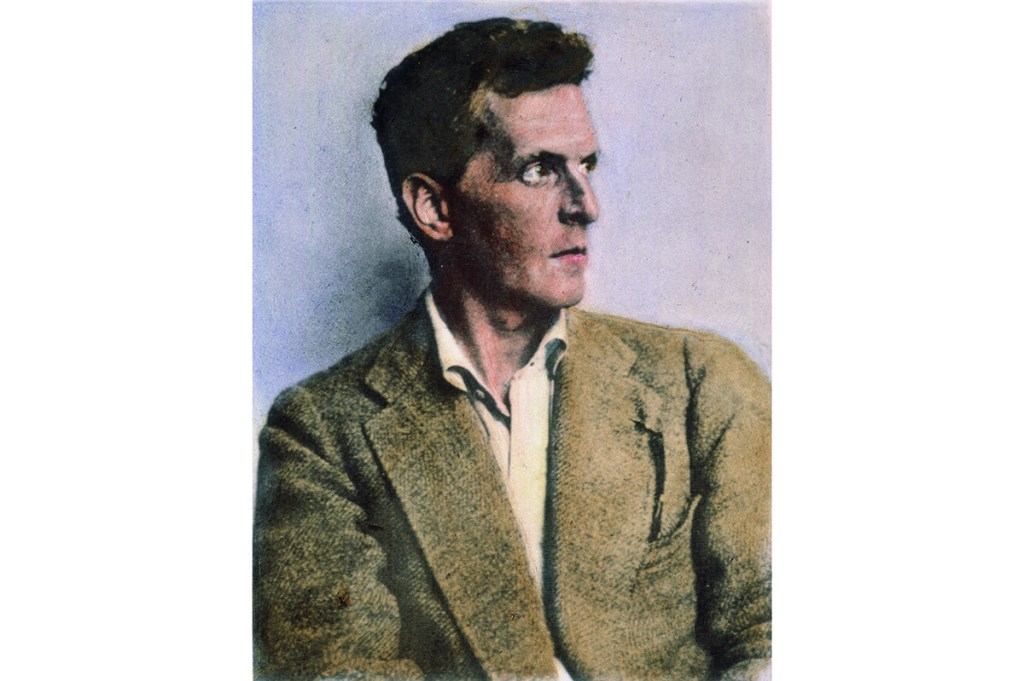

When Ludwig Wittgenstein died in 1951, he had only published one book — the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which was first translated into English in 1922 (with an introduction by Wittgenstein’s former professor and mentor Bertrand Russell, to which Wittgenstein strongly objected). Philosophical Investigations, which Wittgenstein was working on at the time of his death, was published in 1953. His wartime notebooks, which he kept between 1914 and 1916, appeared in 1961.

These are important. The Tractatus is famously dense, being composed of a series of statements on the relationship between words and objects and the nature of knowledge. The notebooks provide a clearer sense of the problem Wittgenstein was trying to solve and the progression of his thought. But they were not published in full. There were two sets of notes — one, in German, on the right-hand pages of the notebook, which were the ones published in 1961, and one, in code, on the left-hand pages.

The code is not difficult. It was one Wittgenstein used in childhood with his siblings and consisted of inverting letters of the alphabet — a is z, b is y and so on. But his literary executors felt that the notes were too personal (Wittgenstein keeps track of the number of times he masturbates, for example) and that it would be poor form to publish them, especially given how closely Wittgenstein guarded his privacy when he was alive.

These recently decoded notes, called Private Notebooks: 1914-1916, have now been published in German and English, translated by the Austrian-born literary critic Marjorie Perloff. Perloff argues in her introduction that the notes are important as a means of unpicking Wittgenstein, whose big idea was that communication is context. She’s right.

They begin with Wittgenstein’s first year of fighting in the war and end the year before he was captured in Italy; regrettably, three sets of notebooks have gone missing. Wittgenstein surprised his Cambridge friends when he enlisted in the Austrian army a day after the Austro-Hungarian Empire had declared war on Russia. He had a medical deferment because of a hernia but enlisted nonetheless — not as an officer, which would have been expected given his standing as a member of one of the wealthiest families of Vienna, but as an infantryman. He served first on a patrol ship on the Vistula River, then in an artillery workshop and finally on the front lines.

Wittgenstein didn’t join the war out of patriotism. In fact, he thought England — Austria-Hungary’s staunchest enemy during the conflict — the better country. Instead, he hoped the war would give him a new lease on life (he had been frequently depressed and had previously contemplated suicide) and help him make progress on his “work” — the Tractatus.

He is in good spirits in his first entry, praising the “unbelievably friendly” military officials, whom he finds “enormously encouraging.” This sunny view of his fellow servicemen didn’t last long. While Wittgenstein almost never complained about the war effort or the decisions of the officers, he regularly groused about how he was treated by fellow soldiers, calling them “a bunch of swine” and a “pack of rogues.” “No enthusiasm for anything, unbelievable crudity, stupidity & malice,” is how he describes them in one of many unflattering entries.

He worries that he will display cowardice when the fighting starts but earns the Silver Medal for Valor, Second Class, for manning an observation tower under heavy fire. He also records his progress — or lack thereof — on his “work.” Surprisingly, he is most productive during bombardments and almost incapable of progress when it is quiet and he has nothing but time at hand. Imminent death apparently provided him with a sense of both urgency and clarity.

The other thing he does in his journal — other than recount moments of “erotic feelings” — is pray. A lot. This isn’t just a figure of speech for Wittgenstein, Perloff argues in her introduction, but an earnest address to God. “Perhaps the proximity to death,” he writes in one entry, “will bring me the light of life! May God enlighten me! I am a worm but through God I can become a man. May God stand by me. Amen!” The notebooks are full of such heartfelt prayers.

Wittgenstein’s father was Jewish, but Ludwig was raised in the Catholic Church. He went through a period of searching, but his time in the war seems to have rekindled a faith in some sort of divine being. He read and was deeply moved by Tolstoy’s The Gospel in Brief, which became a kind of Bible to him. “Over and over again,” he writes, “I say to myself the words of Tolstoy, ‘Man is helpless in the flesh but free in the spirit.’” He adds: “May the spirit be within me!”

In the final private notebook, Wittgenstein is calmer, less angry, but still asks God to help him live in the spirit. On one of the adjacent pages of this notebook, he writes: “Life is the world… The meaning of life, i.e., the meaning of the world, we can call God.” In the Tractatus, we have “The world and life are one.”

Wittgenstein said the war saved him. These private notes confirm this.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.