Elliot, 28: “My greatest achievements in life are: drinking a bottle of Listerine in 10 seconds, beating my laptop at chess on easy difficult and surviving till the age of 28.”

Frank, 40: “Professional career, into extreme sports and stay fit, yet also enjoy the finer things in life like diner [sic] and a glass of champagne.”

These were the first two Tinder profiles I saw when I opened the app after watching Netflix’s The Tinder Swindler. They capture the fairly gormless but harmless nature of most male Tinder profiles, with fairly gormless but harmless men attached. Well, not just gormless: I’ve been on enough Tinder dates to know that there are plenty of unreliable, sometimes cruel, often inconsiderate and flakey (or angry) men on there. And Tinder certainly has its share of bad apples — reports of romance fraud went up by 40 percent in the year up to April 2021. But you’d have to be very unlucky to encounter anyone in remotely in the same league as Israeli fraudster Shimon Hayut, whose gobsmacking deceptions are the subject of the documentary.

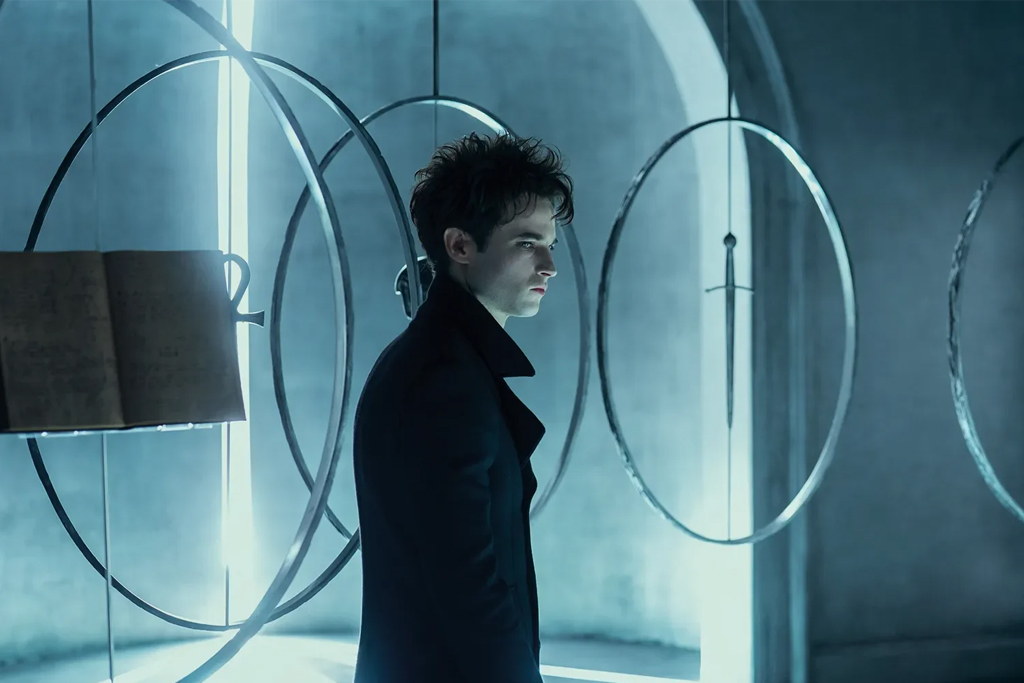

Hayut went by, among others, the name of Simon Leviev, pretending to be the scion of the Israeli Leviev diamond dynasty. He defrauded his pretty, loving female dupes of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The son of a rabbi father and hunchback mother (whom we briefly glimpse in front of her flat when journalists go in search of clues to his whereabouts), Hayut is from B’nei Brak, a poor, ultra-Orthodox city near Tel Aviv — a far cry from the life of private jets and Champagne he disappeared in search of. He lured women with sophisticated forms of emotional manipulation and then, pretending to be in mortal danger from ruthless enemies that required him to get rid of all his credit cards lest he be traceable, he got them to take out cards in their names. The extravagant loans from the cards he then used to wow and build trust with his next victim.

What hits home about the story isn’t the existence of bad apples — there have always been those, even if Tinder has enabled them in new ways. Rather, it’s that Hayut’s particular way of reeling in his victims eerily reflects, and could only function within, the slippery cadences of intimacy in app-land. In other words, it’s the communication culture spawned by Tinder itself that is the biggest menace: it is fundamentally untrustworthy, a cascade of shifting sands, behind which lie a range of unsettling but characteristic behaviors. There is “ghosting” (suddenly cutting contact), “benching” (keeping several options going at once to offset uncertainty about your main squeeze), “breadcrumbing” (sending out flirtatious, non-committal signals), “cushioning” (checking out other options while in a relationship), “half-night stands” (leaving straight after sex) and so on — almost all ways of treating people like low-value, fungible commodities worth keeping at screen’s end only for their minor ego-boosting services.

These behaviors keep dating incredibly suspenseful. It’s a suspense that unfolds in the nuances, often the micro-nuances of instant messaging and social media, while you wait to find out what you’re really dealing with, and whether it matches what, in rare cases, you so desperately hope it is. The Tinder Swindler excellently and stressfully captures the visual and aural experience of this: the notification, always pulsingly alive, that someone is online, the mystery about whether they really are staring at their screen and if so, what it means if a message is not sent, especially after it looks like they’ve begun writing. The terrible wait while it says “typing” on WhatsApp or as that ripple of dots unfurls on iMessage. What is coming? Will it light your world up with the effervescence of a heart or kiss emoji, fall flat with a deadening full-stop or unanswerable piece of whimsy, or ask for something not quite right, as Hayut did, again and again, more and more pressingly?

The documentary captures the building pressure on the victims as the tsunami of notifications accelerates: the frantic messages on text and WhatsApp, the voice calls, the Facebook messages and Messenger calls, hearts and kisses and desperate pleas — and finally, anger and threats. It is all smoke and mirrors, of course, an effect made possible at blistering speed and intensity by the technology to hand. Within this communicational sphere, Hayut’s relationship-building style is eerily familiar too: there’s the rapid acceleration from almost nothing to “I miss you,” the use of “baby,” the excessive use of heart emojis, the “good morning” messages.

I still hear from a youngster I met on Tinder in Italy a few years ago, who talks to me like we’re the oldest, closest of lovers, suggesting saucy weekend breaks in Paris or Milan. But we met only twice and had an unremarkable bond; after the second meeting, he went silent for months. Then there are the ones who leave repeated voice notes asking about your life, demanding minute-by-minute updates of what you’re up to, as if every detail is suddenly of the utmost importance — all this before you’ve even met. With these ones, the lines tend to go abruptly dead after the meeting — if you even manage to get to that stage. Forms of emotional fraud from the subtle to the heartbreaking are Tinder’s currency; frauds like Hayut’s are merely a starkly materialized version of it.

Audiences mocked the swindled women for having got their just desserts for being “gold-diggers,” which is apparently what you are if you delight in being offered a ride on a private jet by a handsome, dashing date. Such accusations should be rejected as simple misogyny, and the victims’ initial delight in Hayut’s luxurious offerings seen rather in terms of yet another weird Tinder dynamic: that of open possibility, that in meeting anyone, anything could happen, wonderful or terrible; the tenacity of the hope that perhaps a Prince Charming really will come to wipe away the bad taste left by all the frogs and make it all worth it. These women were not greedy: they were just unlucky enough to come up against a nightmare masquerading as a fantasy.

This article was originally published on Spectator Life.