“Why are the Wisest ever the most easy and content to die, and the Weak and Foolish the utmost unwilling? Is it not, think you, because the most Knowing perceive, they are going to change for a happier State, of which the more Stupid and Ignorant are uncapable of being sensible?”

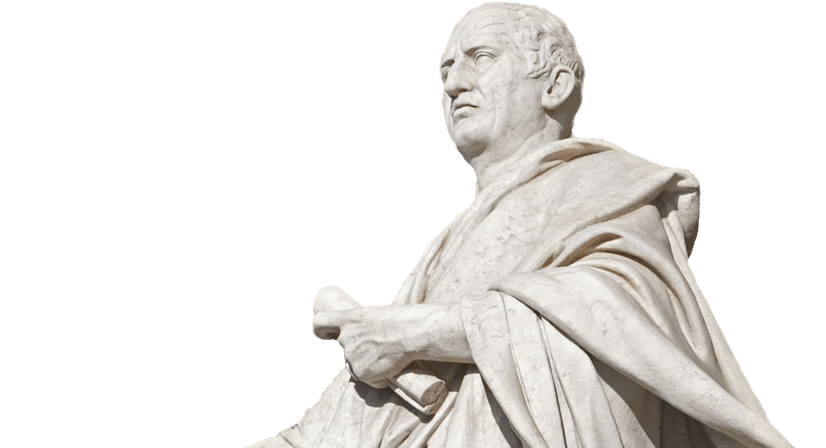

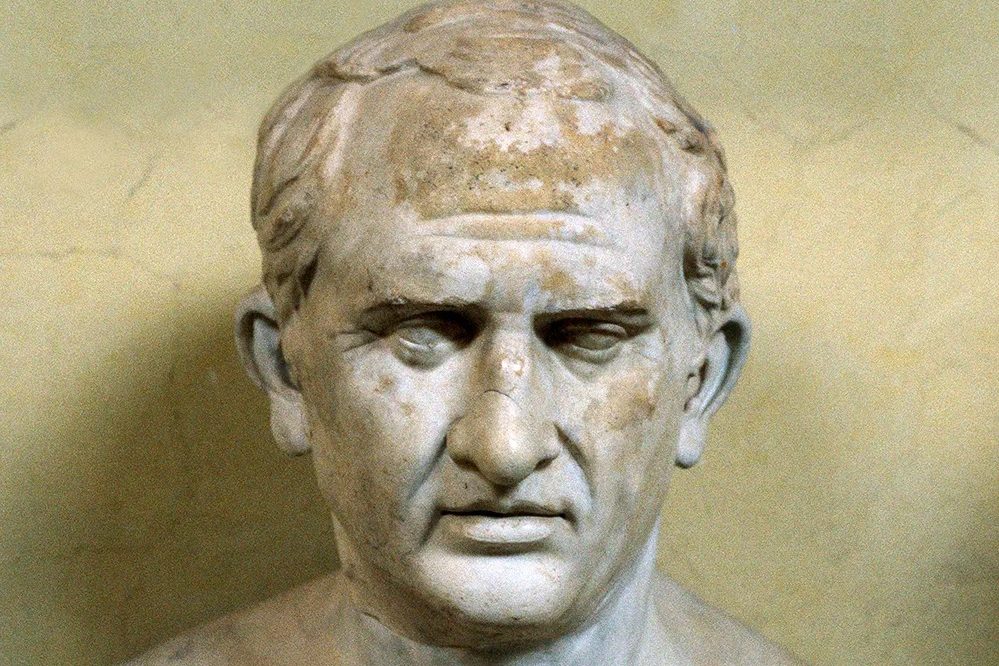

Thus wrote Cicero in On a Life Well Spent, a 2,000-year-old essay. The English version I possess was published by Benjamin Franklin in 1744, and it was beloved by the Founders, one of the most remarkable generations to have graced the North American continent.

Well, so people used to think. Recent reappraisals of history — a la the 1619 Project, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s “Teaching Hard History” curriculum, and even the Broadway show Hamilton — have thrown a wrench into the long-held mythos of the American founding. Rather than a brilliant crew of patriots who sought to create a new country around principles of freedom and civic virtue, the Framers were, according to this new narrative, a cabal of racist, greedy oppressors who aimed to perpetuate a patriarchal society reliant on slave labor. Thus are the teachings of those “old white men” now also held suspect.

Which is fitting, in a way. Cicero was an old white male. So was most of the founding generation, even if Thomas Jefferson was thirty-three at the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and James Madison was thirty-six at the Constitutional Convention. Either way, it’s not a stretch to imagine that woke scholars and their acolytes believe the Founders’ love of the ancients was itself a weapon to sustain patriarchal, autocratic norms. As if Washington, Franklin and the rest conspired in smoke-filled rooms to persuade future generations that Plato and Seneca are worthy of reverence because they served to buttress their own systemically oppressive regime.

It’s not just America’s “first” generation that is taking a beating from the “chronological snobs,” as CS Lewis called those who stand in arrogant judgment over all earlier ages. Even the “Greatest Generation,” which lived through the Great Depression, sacrificed during the Second World War, and brought the Soviet Union to its knees, is increasingly viewed as guilty of the same alleged bigotry as their eighteenth-century predecessors. Many were taught to view the post-war era as a time of unprecedented prosperity (concurrent with high levels of civic participation and religious observance), but activist scholars note that black Americans continued to endure injustices like redlining, white flight, a systemically racist justice system, and even white theft of their cultural heritage, as one 1619 Project author argued (shame on you, Elvis).

Such appraisals have been on my mind of late, especially since the decline and recent passing of my grandmother, who died in mid-December in Hampton Roads, Virginia, at the age of 99. She was perhaps the epitome of every glowing caricature of the Greatest Generation: born in Kansas in 1922 to poor Irish Catholics, she lived through the Dust Bowl, worked in a powder plant during World War II, raised a family of five while her husband ran a small business, and was deeply invested in community service and religious activities. When one of her adult daughters unexpectedly died leaving two small children, she and my grandfather adopted them.

My grandmother personified stability, sacrifice, and selflessness. She never wavered from her Catholic faith, and shares responsibility for my own return to Catholicism in my 20s. She asked little, if anything, from anyone, and relentlessly gave of herself to family and friends. One of my favorite stories involves her famous chocolate chip cookies, which she carefully mailed to my cousin (one of the ones she raised) while he was deployed in Iraq more than ten years ago. Al-Qaeda in Iraq blew up that shipment before it could reach him. “Then it was personal,” my cousin jokes.

My grandmother’s qualities are the very ones that Cicero lauds. He praises the elderly man who “had no Reason to complain of Life, nor did he feel any real Inconveniency from Age: An Answer truly noble, and worthy of a great and learned Soul.” He exhorts readers to orient their lives to transcendent ends and blessing future generations: “I do it, he will say, for the Immortal Gods, who, as they bestow’d these Grounds on me, require at my Hands that I should transmit them improved to Posterity, who are to succeed me in the Possession of them.” And he urges us to accept each new stage of life with simple gratitude: “While you have strength, use it; when it leaves you, no more repine for the want of it, than you did when Lads, that your Childhood was past: or at the Years of Manhood, that you were no longer Boys. The Stages of Life are fixed.”

When I saw my grandmother for the last time, looking a bit more tired and despondent than usual, she made it clear she was ready and willing to accept what God had in store for her. Says Cicero: “We ought all to be content with the Time and Portion assigned us. No Man expects of any one Actor on the Theatre, that he should perform all the Parts of the Piece himself: One Role only is committed to him, and whatever that be, if he acts it well, he is applauded.”

That well describes not only my grandmother, but millions of other members of the Greatest Generation, who made do through each new national and personal crisis. They kept themselves, in Cicero’s words, “constantly employed,” perhaps a consequence of having lived through one crisis after another. Their legacy is one of the most powerful and most noble societies in human history, defined by “a well spent Life preceding it; a Life employed in the Pursuit of useful Knowledge, in honourable Actions and the Practice of Virtue.” For all their failures, how can we credit to them any lesser praise, given not only the defeat of fascism and communism, but a good-faith attempt to rectify centuries-old historical racial injustices?

It is hard not to feel a sense of shame when comparing myself both to the generation of my grandmother and that of America’s founding. What have I done with the cultural, economic, and political inheritance bequeathed to me by those who have come before? Have I sufficiently accepted the mantle of responsibility and sacrifice that millions of Americans before me gladly betook? Can my sacrifices in any way compare to those who have preceded me?

I fear few in my generation are even pondering such questions. They are too busy casting aspersions on those who created the comfortable world they now inhabit. Yet if America — and the West — have any chance at survival, we must approach our past with humility and charity. It is what the Founders did when they sought to build a nation based on eternal principles of justice and virtue. It is what our grandparents did in seeking to protect those principles for their own progeny.

If we, however imperfectly, can do the same, we too may be able at death’s door to declare what Cicero asserted with such remarkable confidence: “[Death] is to be valued, and to be desired and wished for, if it leads us into another State, in which we are to enjoy Eternity.”