No matter how many years have passed since they first hit American airwaves, or how many of its members have died, or how aged its surviving members have become, the Beatles will always be, in our minds, forever young.

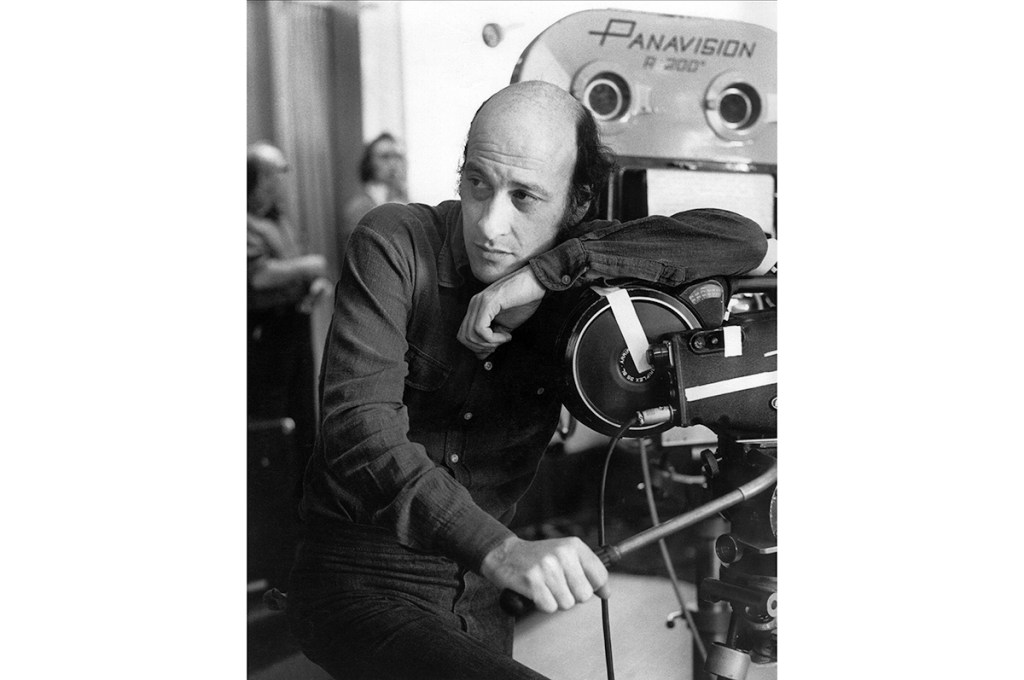

To a large extent, the public perception of John, Paul, George and Ringo as personifications of youth, zest and zeal was a byproduct of their classic faux-documentary musical comedy, A Hard Day’s Night, released in the summer of 1964, just months after their appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. It comes, then, as something of a shock to note the ninetieth birthday this month of the film’s prodigious and gifted director, Richard Lester. The maker of the Beatles movies (he also directed 1965’s Help!) a nonagenarian? It can’t be!

But so it is. Born in Philadelphia in January 1932, eight years before Ringo Starr, Lester settled in England as a young man. His earlier films — The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film (1959), It’s Trad, Dad! (1962) and The Mouse on the Moon (1963) — were lively, hip affairs, and he lent A Hard Day’s Night the same spirit of untamed frivolity. All those shots of the young gents in trim dark suits racing around, goofing off and talking back have the joyous spontaneity of the film’s New Wave antecedents, Godard’s Breathless (1960) and Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1962).

Yet the idea that Lester at ninety is an aging hippie — a kind of Peter, Paul or Mary of cinema, clinging to his thinned-out sideburns and blanched-out love beads — is belied by his subsequent films, which, surprisingly, show him to have been a man older than his years. In fact, since at least the mid-1960s, Lester seemed to regard the freedom and nonconformity of the Beatles as, at best, an unfulfilled promise and, at worst, something of a bill of goods. The first film he made on the heels of A Hard Day’s Night — 1965’s black comedy The Knack… and How to Get It, starring Michael Crawford as a naive fellow who wishes to emulate the ways of a cad — takes a far more somber view of Swinging London.

By the time of Petulia (1968), Lester had sloughed off any lingering sentimentality for the hippie generation. This sharp-edged study of late-Sixties San Francisco places on a collision course two types of the period: a straitlaced, middle-aged physician (George C. Scott) and a feral flower child (Julie Christie). But instead of the latter predictably schooling the former, both end up damaged, discontent, despondent. No less morose were How I Won the War (1967), a send-up of World War Two, and The Bed Sitting Room (1969), a satire of an imagined World War Three.

Lester was aware of his shift in attitude. “One has to look at films made in the early Sixties with the eye of someone from the Sixties,” he recalled in a 1998 documentary. “We were in a very exuberant time. Things were good. Things were being tried. We all felt that there was a fresh wind blowing.” But hangovers and Hanoi quickly dampened the mood: “You then have to look at the films made in the late Sixties — not only mine but everybody else’s — with that sense of disappointment.”

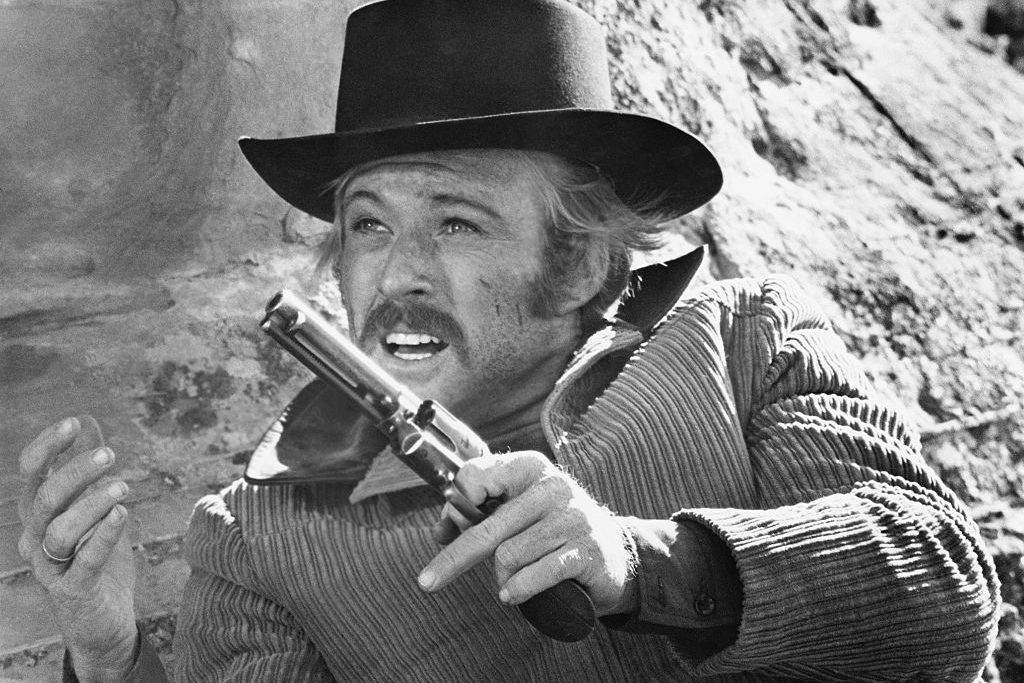

Bit by bit, Lester became estranged from contemporary culture. The filmmaker once so plugged into the zeitgeist contented himself with elaborate period-piece recreations of the past: The Three Musketeers (1973), The Four Musketeers (1974) and Royal Flash (1975). Most intriguing was his 1976 Robin and Marian, a film that gives us Robin Hood (Sean Connery) and Maid Marian (Audrey Hepburn) at middle age, replacing youthful adventure with regret-tinged romance.

That same tone informed Lester’s contributions to the Christopher Reeve Superman series, including the masterly Superman II (1980). Here, the intense but mutually selfish love affair between Clark Kent and Lois Lane ultimately proves incompatible with Clark’s day job as the Man of Steel, a comic setup that Lester renders solemn. The ending, when Clark kisses Lois to wipe away her knowledge that he’s Superman and thereby permit him to continue saving the planet, is among the great farewells in film. This is a director attuned to disappointment and disillusionment.

As the years went on, Lester’s gifts never ebbed. In the fleet, funny, ocean liner-set disaster flick Juggernaut (1974), he spiced up the action with incidental gags, such as passengers playing ping pong on choppy waters. By his retirement in 1991, few could equal Lester’s eye for framing or ear for timing.

We may be conditioned to regard the Beatles as eternal post-adolescents, but let us honor Richard Lester, in the ninetieth year since his birth, for honing a fully mature craft — one that continued to develop and deepen, long after the lads from Liverpool quit singing.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.