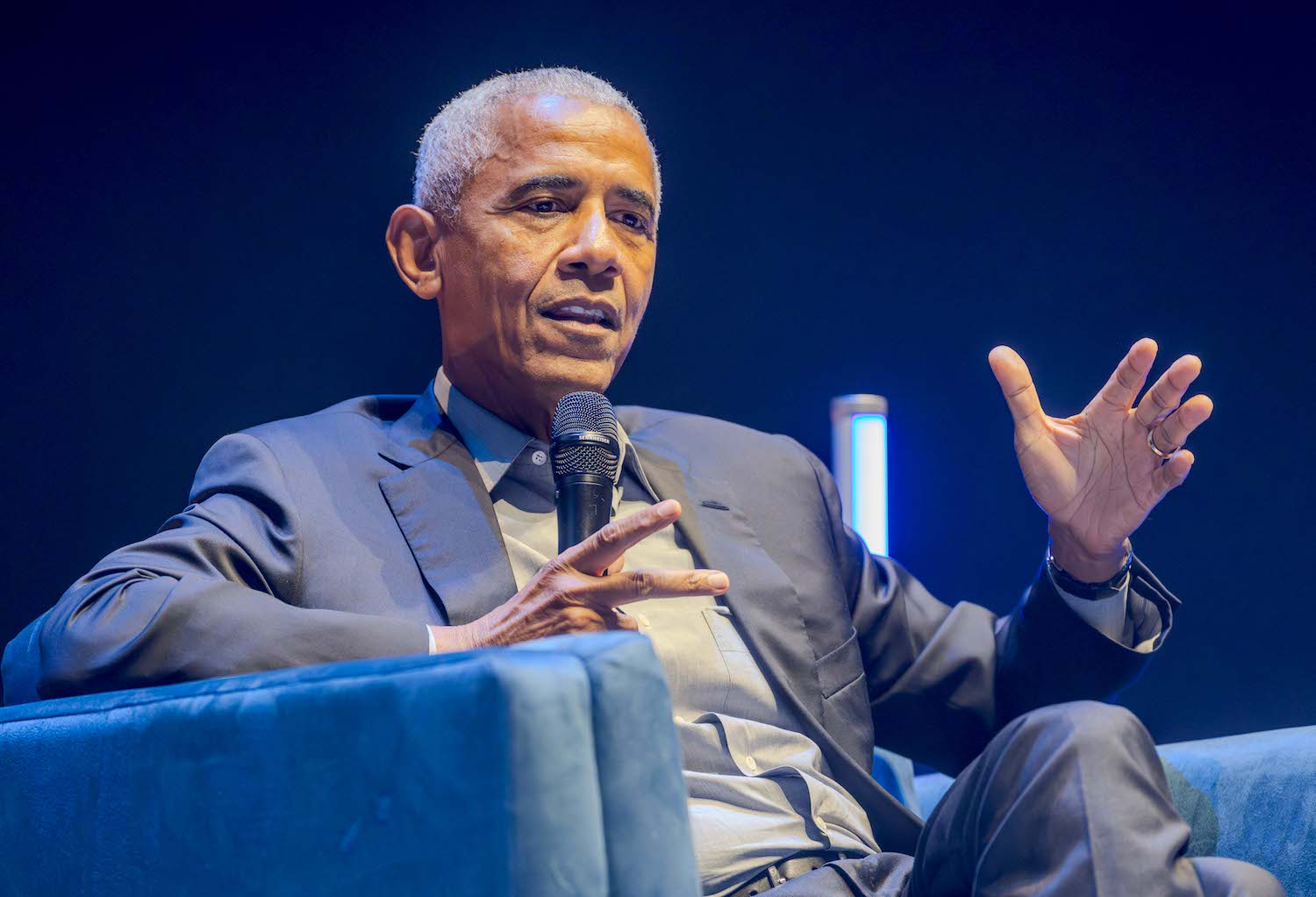

Barack Obama exited the presidency far blacker than he entered it. That’s a central theme of historian Claude A. Clegg III’s splendid and wide-ranging “interpretive history” of how Obama’s White House years “were witnessed, experienced, and interpreted by African-Americans.”

That framing reflects a book that is self-consciously aimed at black readers, but it also illuminates an important truth about Obama, one that this reviewer realized after spending more than eight hours talking with him during three “off-the-record” visits to the Oval Office during the last nine months of his presidency.

Clegg is too good a historian to be an uncritical fanboy like the many journalists who forfeited their professionalism during the Obama years. He grasps the hopeful ambivalence with which many black Americans responded to the “boundless ambition” of Obama’s self-created life-story, noting how the comedian Chris Rock called him “our zebra president. …We ignore the president’s whiteness, but it’s there.” Likewise, the distinguished actor Morgan Freeman bluntly observed that “He’s not America’s first black president, he’s America’s first mixed-race president.”

Clegg also grapples forthrightly with the reluctant yet widespread recognition that Obama’s presidency failed black Americans to a painfully surprising degree. Many African Americans “endured the greatest economic disaster in generations under the leadership of a Black president whose ability to redress their plight was more circumscribed than many had previously understood.” In one reflection of just how broad Clegg’s research ranges, he calls out Obama’s stark failure to issue more than a tiny handful of pardons and commutations (at least until the very last part of his presidency), declaring that this made him “the most merciless president in more than a century.”

The Black President is also unflinching in its acknowledgement that Obama was as far from a “woke” defund-the-police radical as any black Democrat could imaginably be. “Obama proved to be a stalwart ally of the law enforcement community,” Clegg writes, as was seen in August 2014 when widespread rioting followed the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Obama forcefully declared that “there is never an excuse for violence against police, or for those who would use this tragedy as a cover for vandalism or looting.” Such a forthright declaration is even more striking now, following the widespread criminal violence that has wracked the US, than it was seven years ago.

Even as a presidential candidate in 2007 and ’08, Obama never shied from addressing black America’s intramural shortcomings, and Clegg acknowledges how that remained the case during his eight years in the White House. “Obama’s advocacy of individual agency, communal responsibility, and the merits of hard work never changed, and he was as critical of what he believed to be deadbeat fathers and cultural pathologies in his second term as he had been during his first.”

What did change over the course of Obama’s presidency, and indeed within Obama himself, was a conscious appreciation of just how great a role his visible racial identity played in defining Americans’ reactions to him. In July 2009, after only eight months in office, Obama offhandedly commented on the unwarranted detention of his friend Henry Louis Gates by observing that the arresting officer had acted “stupidly.” His approval rating among white polling respondents dropped measurably and never again rose above 50 percent. That led to a pronounced presidential reluctance to address racial questions that endured until well after his 2012 reelection victory.

In late April 2015, following the death of Freddie Gray in a Baltimore police van, Obama exhibited his greatest “candor, earnestness, [and] exasperation” about racial injustice when he complained that “we just don’t pay attention when a young man gets shot or has his spine snapped.” To Clegg, this was “a newly revealed President Obama,” and one who eight months later, in a December 2015 interview with National Public Radio, went a good bit further in commenting that “the specific virulence of some of the opposition directed towards me…may be explained by the particulars of who I am.”

That was the Barack Obama to whom I listened on three occasions between April and December 2016 in the Oval Office and the more private President’s Dining Room just to its west. There was no doubt whatsoever that Obama had processed much of the vituperative hostility towards him through a racial lens, and one could easily walk out of the White House thinking that Obama had blamed much of the opposition that had limited if not shackled his presidency on an unexpected resurgence of American racism.

Claude Clegg’s thorough and thoughtful history points in exactly that same direction, highlighting Obama’s “growing tendency to more openly discuss race” during his presidency’s final months. The Black President reports how an October 2016 poll showed that 57 percent of African Americans and 40 percent of whites believed that US race relations had worsened during the Obama presidency, a development that stood in dire and painful contrast to the halcyon scenes that had marked Obama’s November 2008 election victory and January 2009 inauguration.

Speaking to Clegg in 2020, black Baltimore pastor Reverend Dr. Stanley Fuller voiced a profound and powerful coda: Barack Obama’s presidency “made more of a difference to Caucasians than it did to us. …Donald Trump is only president because Barack Hussein Obama was president.”

David J. Garrow’s books include Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama and Bearing the Cross, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Martin Luther King, Jr.