Godine at Fifty: A Retrospective of Five Decades in the Life of an Independent Publisher, by David R. Godine, David R. Godine, 2021

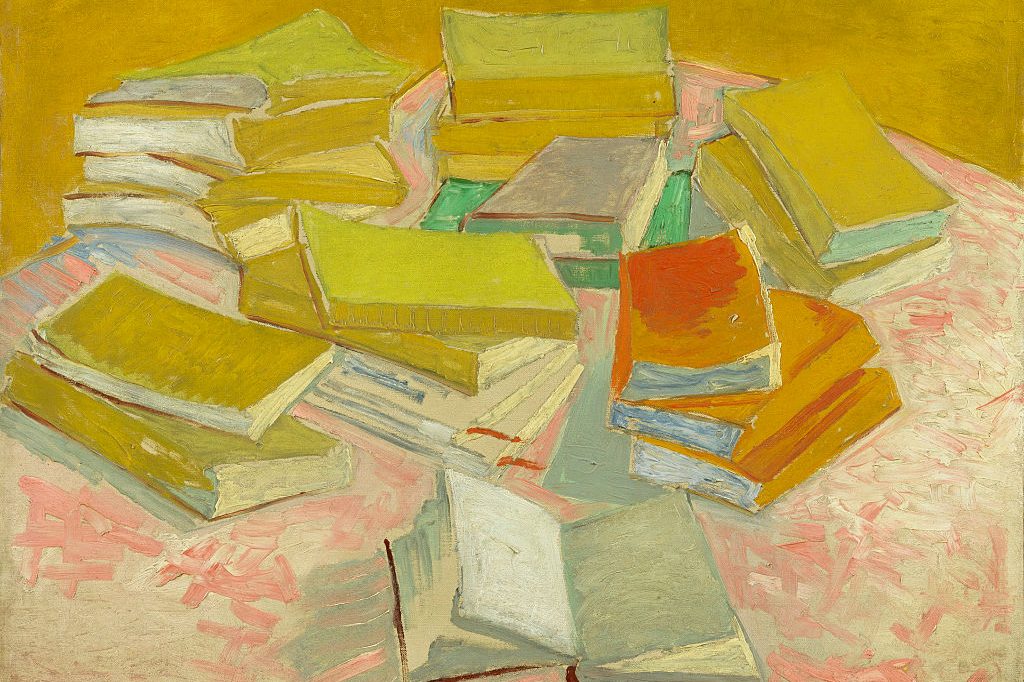

In The Truth about Publishing, Sir Stanley Unwin writes: “It is easy to become a publisher, but difficult to remain one.” David R. Godine has accomplished the difficult task of remaining one for fifty years, and in the beautifully designed and set Godine at Fifty — would we expect any less from a Godine book? — he tells the story of the company’s beginning and survival and of each book he has published over the years, chock-full of reproductions of the company’s covers, woodcuts, and illustrations. This is a book about books for book lovers.

Raised in Boston, David R. Godine got his start in printing at Dartmouth, where he met the head of Dartmouth Publications, “a scholar of the history of graphic art, a fine teacher and a devoted mentor.” Godine worked with him for three years in his shop before spending a term at Oxford’s Bodleian, two weeks at France’s Bibliothèque nationale, and a week in Greece.

His first job after graduation was at Gehenna Press in Northampton, where he learned “how to insert paper into the jaws of the Thomason laureate without losing a finger, how to create the make readies for Leonard’s detailed and exquisite engravings that required endless fussing with thin strips of India paper, and how to run the big Kelly Two 38” cylinder press.” A few years later, Godine rented an abandoned barn (at the price of one book a month) from a local farmer in Brookline, Massachusetts to start his own letterpress company. Before too long, he began producing his own books and shifts from letterpress to publishing.

The company benefited early on from the amount of money the federal government, afraid of “being left behind by the Soviet Union,” was giving to libraries. This meant, Godine writes, that a review in Publishers Weekly or Library Journal, “even a bad review, would guarantee a minimum sale of a thousand copies.” Still things were tight:

The company was consistently undercapitalized, always starved for cash. The unsung heroes were certainly the string of business managers . . . who had to put off and humor creditors with one side of their mouth while trying to collect money with the other. There was never any reserve for paying royalties, and when those days of reckoning came twice a year, it often took a full two months of dedicated work to manually tabulate sales, apply them to the terms of each contract, and find the cash to pay them, or at least some of them.

But the real reason for the company’s success has been its carefully chosen and eclectic list of books, all exquisitely designed and set. It was the personal interests and good taste of Godine and his staff, not market analysis, that drove the company’s acquisitions. “Since we started as printers and hand ink under our fingernails for the first decade,” Godine writes, “the long and broad history of printing . . . held particular interest. I sail wooden boats, fish with flies, and weed gardens, so these activities are represented.” The company is also known for its history and biography lists, books on language, and children’s books. Because “every self-respecting publisher has a moral obligation to support” poetry, Godine published full-length works by Wesley McNair and Donald Hall, and chapbooks by X. J. Kennedy, John Hollander, Mary Baron, and others.

As an industry, publishing is one of the least suited to algorithms and modern market research — at least this is my irrational hope for which I have no evidence whatsoever. Readers like to be surprised, and good publishers do, too. Godine remarks that one of those pleasures of publishing is that you never knew what each day or each book would hold until it was done.

It is, perhaps, Godine’s background in setting type and producing woodcuts that has made him so gifted at producing beautiful books that feel just right. You see this attention to detail in his account of every book — yes, every book — he has published. Take The Autobiography of Michel de Montaigne, for example, translated and edited by Marvin Lowenthal and published in 1998. “The typesetting of this book,” Godine writes, “demonstrates how important typography and choice of type can be to a book’s attractiveness and readability,” and so “Scott Kosofsky created an entirely new font” for the book.

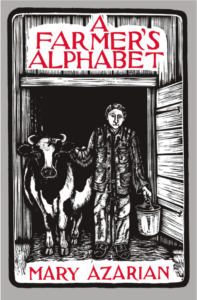

A Farmer’s Alphabet was acquired by Godine after his neighbor showed him flashcards she had been using in her elementary school classroom, which had been designed by a woman in Vermont. Godine drove up to visit her. When he arrived, she was “cutting pine furiously in a small shed adjoining her house while her then-husband was out plowing the fields with oxen.” The book was shortlisted for the Caldecott Medal and has remained in print since it was first published in 1981.

A pleasure to read and hold, Godine at Fifty is no self-serving promotional work. It is a tactile example of the company’s policy to produce beautiful, worthwhile books at a fair price. It is also a piece of history and a guide to some of the best books published in the last half-century.