Shukria Abdul Wahid has nine children, two boys and seven girls. All they had to eat yesterday, she says, were two small pieces of stale flatbread — for the whole family. She and her husband went without. They couldn’t even have tea to quieten their own hunger pangs. The gas bottle used to boil water ran out long ago and there is no money for another one. She tells me it is unbearable having to say “no” to her children all day when she doesn’t have a scrap of food to give them. “They are very little. They do not understand the situation, they do not know what’s happening in Afghanistan,” she says. “So they just keep begging — ‘Give us something to eat. We are hungry’ — and they won’t stop crying.”

An aid worker for an Islamic charity found Shukria for me in the Afghan capital, Kabul. He translated as she spoke into his phone and he sent me photographs. She is dressed in a blue burka and sits on a small rectangle of carpet on a bare concrete floor. Her children squeeze on to the carpet around her and look up at the camera, wide-eyed. The room is tiny — perhaps once a storeroom — and there’s no glass in the windows to keep out the bitter cold of a Kabul winter. They don’t have so much as a blanket for the children, she says. That’s because they had to flee their home in the province of Baghlan when the Taliban swept in. Her husband was a soldier and they were afraid he would be killed. The family could not find food in Baghlan and hunger drove them into Kabul. But Kabul is the same. Her husband goes to the bazaar every day to find work. Most days, he comes home empty-handed and they don’t eat.

The UN, aid agencies and human rights groups are warning that Afghanistan is on the brink of famine. Millions of Afghans are already in what the UN calls a “food emergency.” They are not starving yet, but a few more missed meals may bring them close to that. For people like Shukria, this means making awful choices to survive. She is terrified of losing a child to hunger (or cold) this winter and so she tells me that only the day before, with nothing left in the house, she came to a decision. “We hope from Allah that our lives will be better in the future. But everything is so difficult. It just seems impossible. I told my husband we had to do something. I said we had to sell one of our daughters — to get food for the other children, to stop their hunger, to save everyone.”

She was talking about selling her daughter into an early arranged marriage. There have been many reports about Afghan families being forced to do this, their daughters given away to whoever can pay. I asked an Afghan journalist in Herat, in the far west of the country, if this was widespread, or just a few stories in the international media. He drove out to a village named Shahrak-e-Sabz, which is known, even in Afghanistan, for its poverty. The place is a collection of mud-brick homes in the midst of a stony desert, a mountain looming in the background. As soon as he arrived — smartly dressed, driving a car, having come from the city — he was surrounded by a crowd who thought he had come to buy a child. Men and women called out to him to come with them so they could sell him one of their daughters. It didn’t take him long before he found a couple who had already done this terrible thing.

Jan Muhammad and his wife Shareen Gull are both in their early twenties. The journalist from Herat sends me a picture of them sitting against the mud wall of their house. He gives them my questions and translates their answers.

As the exchanges takes place, they proudly show off a chubby-faced little girl of seven months named Rahilla. She is their first child, yet they have sold her. They try to explain why. Jan Muhammad works as a laborer and if he’s lucky, and someone takes him on, he gets between fifty and 100 Afghanis a day, between fifty cents and $1. But those days are rare and he usually ends up scavenging for dry bits of bread in Herat. He brings these home and Shareen Gull adds water to make a paste for them to eat. “If he finds work, he brings some soft bread [from the bakery],” she says, “but we haven’t had that in months.”

They could have gone on living like this for a long time, but in August there was a disaster. Jan Muhammed’s brother was arrested and taken to the central jail in Kabul. The family had to pay a bribe to get him out: 70,000 Afghanis, about $750. The timing was terrible. These were the last days of the Afghan government. If only they had waited a few more weeks, they tell me bitterly — the Taliban freed all the prisoners anyway. But they went deep into debt to pay the bribe and there was no money left over for food. Shareen Gull says: “I didn’t eat for a week because of that. We were in despair.”

But then other families told them how to arrange the sale of a daughter and, at four months old, Rahilla was bought by a wealthy goat trader, a man in his fifties. This man promised that the little girl would eventually marry one of his sons, not him, but if he’s lying about that, there is really nothing her parents can do. The goat trader will take her away as soon as she can walk and she will work in his house as a servant until marriage. The down payment for Rahilla has cleared Jan Muhammed’s and Shareen Gull’s debts and they will get another 10,000 Afghanis — a little more than $100 — when the man comes to collect her. Her mother tells me: “If he pays us the rest of the money, we can survive. If he doesn’t come back for her, we will have nothing to live on.” Both parents dream of somehow getting enough money to buy their daughter back one day. “We want to free our small girl,” says Jan Muhammed. There seems no real chance of that.

The selling of daughters used to be rare in Afghanistan, but it is happening much more because of the country’s desperate situation. The UN calls it the worst humanitarian disaster in the world today. Food is short because of a drought over the summer — the most extreme in twenty years — and because fighting stopped the harvest in many places. What’s more important is the fact that three-quarters of all government spending and 43 percent of the country’s income overall used to come from foreign aid. That’s all gone now with the Taliban in charge. It didn’t help that the American-backed government appears to have fled with much of the money in the country’s central bank. The Taliban are broke.

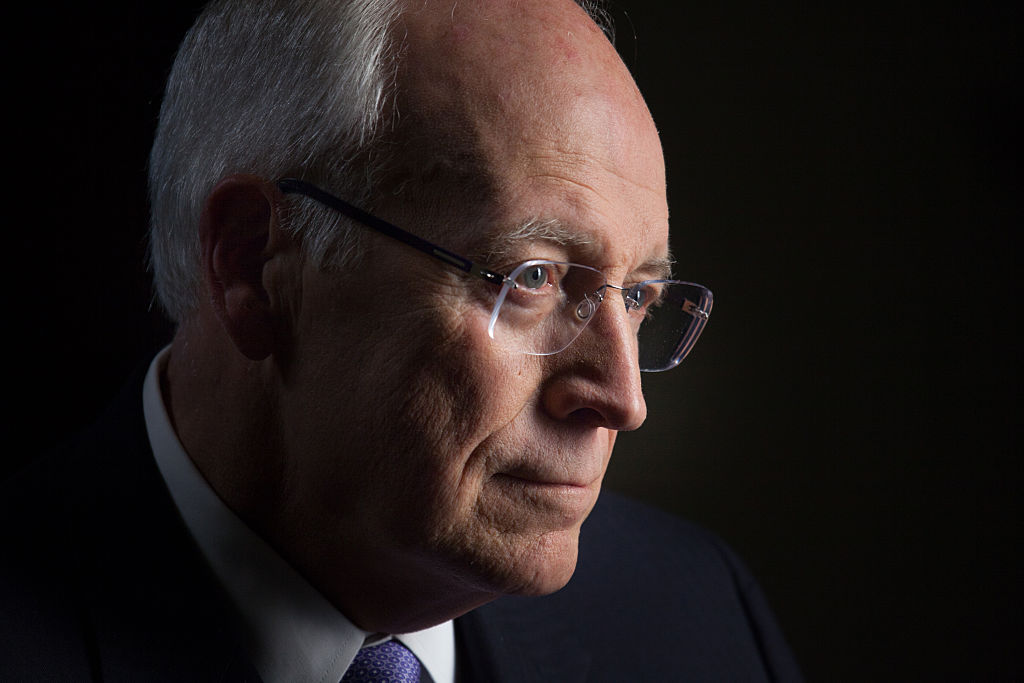

Afghanistan’s new leaders want the billions of dollars that belonged to the old government, which sit frozen in American banks. It seems unlikely that the Biden administration will give it to them. Only last month, a senior US official warned that al-Qaeda were once again thriving under the Taliban. They had the “intention” to attack the American homeland and would soon have the “capability” as well, he said. An Afghan friend tells me it would be a mistake to give this money direct to the Taliban because “they will only steal it.” He is now a refugee in Pakistan and shares with me WhatsApp messages from people who haven’t been able to escape. There are stories of killings and kidnapping, arrests and beatings — and all this while the Taliban are trying to impress the world that they have changed. “If the world helps them out now, they will regret it,” he says. But this is exactly the dilemma facing the international community: whether to trust that the Taliban have changed or watch as millions of people go hungry.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.