In my mother’s final days we had a long conversation about World War Two. I asked if she’d ever thought we might lose. “No,” she snapped. “I knew we were too clever for them.”

The chief of the imperial general staff, Sir Alan Brooke, had been less sanguine. On March 31, 1942 he confided to his diary: ‘During the last fortnight I have had, for the first time since the war started, a growing conviction that we are going to lose.” His concern, besides the army not fighting very well — witness Hong Kong and Singapore — was that Britain’s new allies, the Soviet Union and the United States, were for different reasons clamoring for a second front. The Russians believed the war would be decided that year, and wanted the western Allies to ease pressure on the Red Army. The Americans hoped to end the war in Europe as fast as possible by the direct route to Berlin, with no stratagems of evasion in the Mediterranean, especially not ones tied to British imperial interests.

“This universal cry to start a western front is going to be hard to compete with,” wrote Brooke. “And yet what can we do with some ten divisions against the German masses?” He was referring to the landing being planned in the Pas de Calais — with perhaps the least appropriate code name in the whole war, “Sledgehammer” — to draw off German troops and aircraft from the eastern front.

The idea of diversionary landings wasn’t new. Pitt the Elder had been inordinately fond of them in the mid-18th century, rather than committing to action in decisive strength. But they could never divert enough French troops to make the inevitable losses worthwhile. Opponents at the time described Pitt’s tip-and-run tactics as “breaking windows with guineas.” And as Patrick Bishop observes in Operation Jubilee, physically and psychologically Britain was in no condition to withstand another setback.

Brooke and Churchill were dead set against any invasion, certain that it would end in failure. So perhaps something smaller might serve as a token of earnest, a raid designed more to draw in the Luftwaffe, making use of Fighter Command’s growing strength and reach across the Channel.

Enter Combined Operations Headquarters and Lord Louis Mountbatten. COH had been set up at Churchill’s behest after Dunkirk, a combined (land, sea and air) enterprise to plan, train for and mount offensive amphibious operations independently of the single services whose preoccupations in 1940 were necessarily defensive. Its first director was Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, an officer in the Nelson tradition, the hero of the Zeebrugge raid in 1918, but who, at 68, and impatient with the chiefs of staff committee, was not the success he might have been. In October 1941 Churchill replaced him with Mountbatten, advancing the 41-year-old commodore and distant cousin of the King two ranks to vice-admiral.

Bishop gives a fair assessment of the sudden new member of the chiefs of staff committee, concluding that his “active service record exposed him as a poor battle commander.” Also, and worse perhaps, that his self-regard “colored all his thoughts and actions, private and public” and that “in a position of great authority, which gathered the lives of thousands of men in his hands, the consequences could be fatal.”

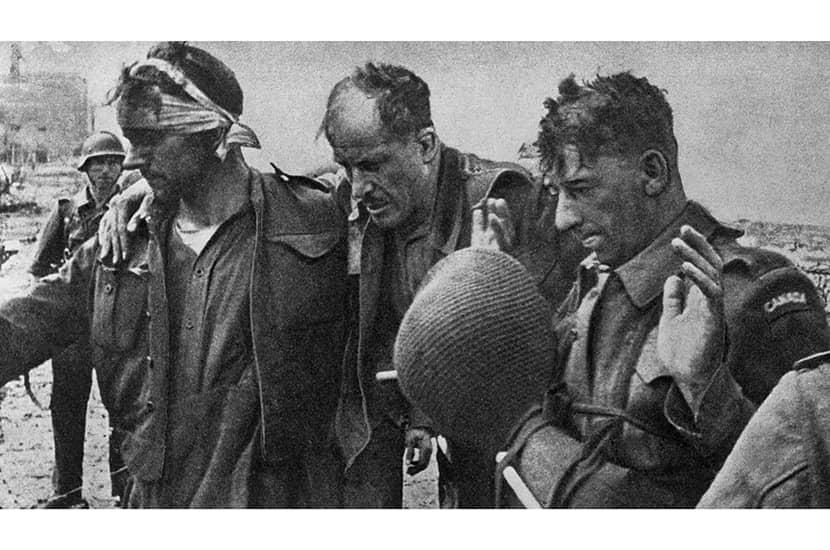

Operation Jubilee in August 1942 was one of the consequences, though others too contributed to the dog’s breakfast. Some 6,000 troops, mainly Canadian, stormed the beaches at Dieppe, supposedly to test the feasibility of a landing and to gather intelligence. Ten hours later, few having penetrated the town, more than half of them had been killed, wounded or captured. The RAF lost 106 aircraft, the navy 33 landing craft and a destroyer.

Bishop’s account of the operation is the best I’ve read. He understands war, he understands battle, and he understands men. He marshals the material well; and there’s plenty of it, for failure generates much paper. The recriminations and attempts at damage control aren’t a happy read. “Dear CIGS, I was absolutely dumbfounded at dinner last Saturday at Chequers, when you made your very outspoken criticism of the manner in which the Dieppe raid was planned,” wrote Mountbatten ten days afterwards, adding that if Brooke didn’t feel able to withdraw his criticism he would have to ask for “a full and impartial inquiry.” Evidently he believed that an inquiry would exonerate him, or else, more probably, that Brooke wouldn’t want an unedifying post-mortem at such a time. Suffice to say, in August the following year, Churchill appointed Mountbatten Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia Command, with promotion to acting (full) admiral. But COH would not be involved with high-level planning for D-Day. A new organization, COSSAC (Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander), was set up.

The enduring question is whether Dieppe was an essential precursor to D-Day; that without the lessons learned, many more lives would have been lost, and even that Overlord might have failed altogether. Bishop argues that because in his heart Mountbatten knew he was responsible not just for the plan but also for the decision to implement it, he played the lessons-learned card disingenuously, telling audiences long afterwards that, comparing the casualty rates of August 19, 1942 with those of June 6, 1944, the lives of 12 times as many men were saved in the latter as a result of the former. Bishop is rightly skeptical, as were many military officers at the time and historians since. Yet I myself am not convinced that without the shock of Dieppe — what Bishop calls the “sobering evidence of the difficulties involved in cross-channel operations” — Overlord would have been a success. That evidence certainly helped check US aspirations for invasion in 1943, yet Brooke continued to harbor doubts right up to D-Day itself. We’ll never know.

But my mother was right. We were too clever for them. We recognized difficulties, if painfully, and were prepared to deal with them. The Germans lost because they could never face the facts.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.