The much-delayed 25th James Bond film, No Time To Die, is finally limping onto the big screen. There are gadget-packed car chases, scarred supervillains and revelations as to the loyalties of supposedly sympathetic characters, but there are also new, socially-conscious elements. Lashana Lynch plays a PoC 00-agent who is very much Bond’s equal at spycraft. Fleabag’s Phoebe Waller-Bridge has been parachuted in as a script doctor, to notify us that this is a post-#MeToo Bond.

Without a simultaneous release on a streaming service, Daniel Craig’s swan song as Bond will stand or fall on its theatrical performance. For all the jokes about ‘keeping the British end up’, a COVID-induced flop could lead the series producers, the Broccoli family, to wonder whether Bond actually has a future at the movies. Do people really want to pay to watch the imperialist and often sexist adventures of a cis white heterosexual man? Or do they prefer the superheroes and gods of Marvel?

If No Time To Die expires at the box office, there remains one last option: the ejector seat. That is, a return to the original Ian Fleming novels and offer a series of faithful adaptations, whether set in the Fifties and Sixties or updated to the present day. This has only been tried once in recent years, with Casino Royale in 2006, at the beginning of Craig’s tenure.

When Craig’s appointment was announced, the press ridiculed him as ‘a blond Bond’, insufficiently handsome and too short. Yet his Casino Royale recovers the steel and nastiness of Fleming’s agent, as well as his sybaritic side. Many of the film’s best scenes involved Bond seducing, or being seduced, by Eva Green’s brittle, witty Vesper Lynd, usually over a bottle of fine Bordeaux or one of the Vesper martinis that Fleming invented in the 1953 novel. A decade and a half on, such moments may seem inappropriate and sexist. And that’s nothing to say of the famous final line, ‘The bitch is dead now.’

As Casino Royale approaches its 70th anniversary, Bond’s original incarnation seems strikingly distant. Fleming named the character after an American ornithologist (on the grounds that ‘James Bond’ was the ‘brief, unromantic and yet very masculine name’ that he needed). The MI6 hitman was a thug in a Savile Row suit: a blunt instrument used by the British government in extremis. He was, nonetheless, charming and irresistible. Vesper calls him ‘very good looking’ and compares him to the songwriter and singer Hoagy Carmichael even as she remarks on his coldness and ruthlessness. The first description of him in the novel remains iconic:

‘His grey-blue eyes looked calmly back with a hint of ironical inquiry and the short lock of black hair that would never stay in place slowly subsided to form a thick comma above his right eyebrow. With the vertical scar down his right cheek the general effect was faintly piratical. Not much of Hoagy Carmichael there, thought Bond, as he filled a flat, light gunmetal box with fifty of the Morland cigarettes with the triple gold band.’

Ian Fleming’s Bond hints at dandyism, an eventful younger life, wit and intelligence, and a love of expensive and intoxicating pleasures. Over the course of the 13 novels and short story collections, Fleming both refined Bond’s character and kept him substantially the same. Bond is a cultured man but also a labels snob: a kind of Patrick Bateman avant la lettre who takes a fetishistic delight in his tailor, cigarettes and Champagne all being ‘the right sort’. Although Bond explicitly states in the final Fleming novel The Man with the Golden Gun that ‘I am a Scottish peasant and will always feel at home being a Scottish peasant’, he is a Scottish peasant who attended Eton, drinks Bollinger and lives in the Christopher Wren-designed Royal Avenue in Chelsea. These are significant social steps up and away from ‘the wee croft’ that his forebears may have inhabited.

Judi Dench’s M might have told Bond that he was a ‘sexist, misogynistic dinosaur’ as far back as 1995’s Goldeneye, but that was with affection. Now, Mr Bond has faced his deadliest and most implacable foe yet: cancel culture. Long called a sadist, a sexist and a snob, 007 now faces a 21st-century enemy more dangerous than SMERSH: Bond is called racist.

The titling of a chapter ‘Nigger Heaven’ in the second Bond novel, Live And Let Die, as well as assorted slighting remarks about ‘negroes’ and ‘negresses’, would lead most readers, woke or unwoke, to similar conclusions. None other than William Boyd, who continued Bond’s adventures in the excellent 2013 novel Solo, described Fleming as ‘an unreflecting racist, probably an unreflecting anti-Semite, right-wing, sexist and homophobe’. Although Boyd immediately qualified his description by saying of Fleming ‘accuse him of being a racist and he’d have been outraged’, his remarks do not seem hyperbolic.

Fleming died at the age of 56 after an eventful life of espionage, flagellation and boozing. As befitted an Old Etonian naval intelligence officer — like his creation — he remained courteous to the end. His last words to the ambulance drivers who were rushing him to hospital were ‘I am sorry to trouble you chaps. I don’t know how you get along so fast with the traffic on the roads these days.’ Lines best delivered in the manner of Roger Moore.

Fleming’s death in 1964 left a gap. The first three Bond films had stuck relatively closely to the novels and had all been successful: clearly a market existed for further adaptations. Glidrose Productions, the vehicle for the Fleming estate, was also keen to keep the character within copyright, so he had to keep appearing in new stories. But Fleming’s death would be fatal for Bond – unless the Bond baton could be handed on to other writers.

Several authors have volunteered to don the dinner jacket and reinvent 007 for a new readership. Kingsley Amis, who adopted the pseudonym ‘Robert Markham’ for his 1968 novel Colonel Sun, portrayed Bond as a humorless vigilante intent on obtaining vengeance for the kidnapping of M, his beloved superior. Sebastian Faulks, who wrote Devil May Care (2008) as a pastiche of Fleming’s style (even taking the credit ‘Sebastian Faulks writing as Ian Fleming’), was almost protective towards his hero: ‘This Bond, this solitary hero with his soft shoes and single under-powered weapon, was a man in dreadful danger… He finds himself in terrible situations, and he’s all on his own — you just worry for his safety.’ Perhaps to offset this lonely, fearful 007, Faulks also insisted ‘My Bond is Fleming’s Bond… he smokes and drinks as much as ever.’

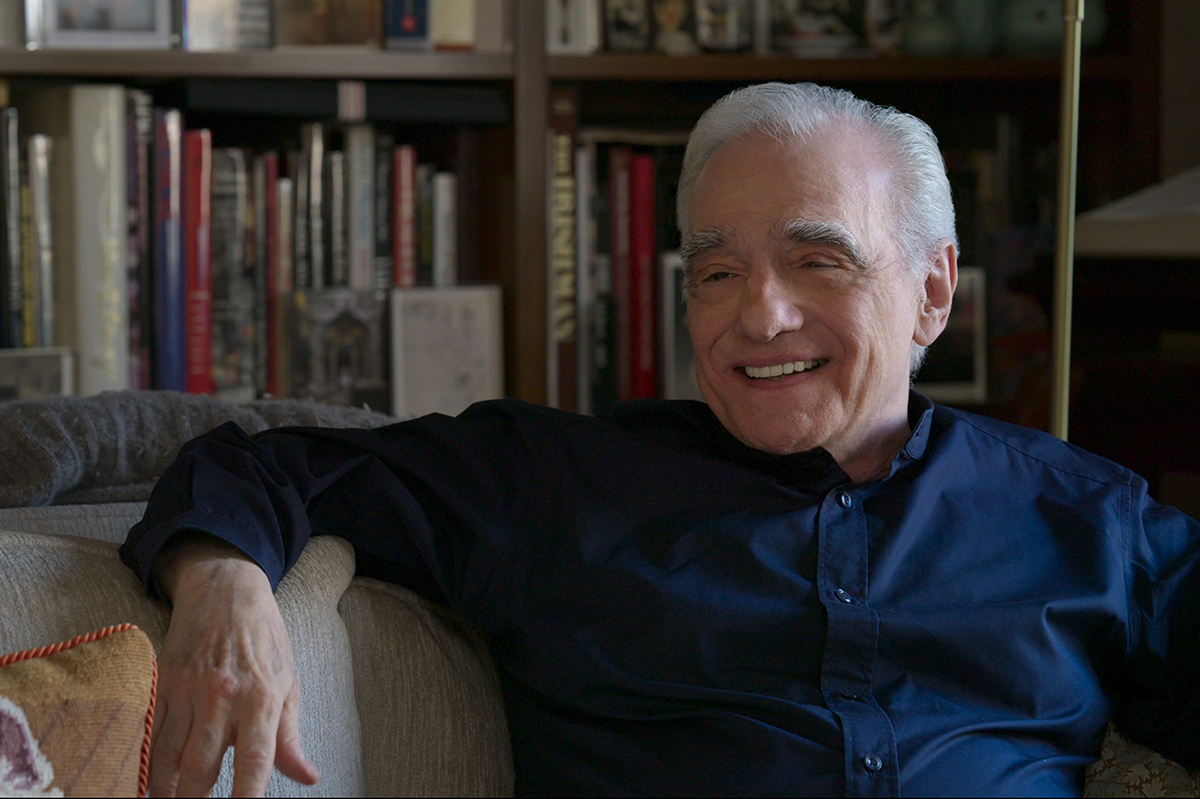

Boyd’s Bond was the most literary and most daring. As he told me:

‘I wrote Solo in my own authorial voice, which was quite different to my good friend Sebastian Faulks. Solo’s a real portrait of Bond as a 45-year-old man, a bit over the hill, an avid reader who quotes poetry, and not English: he’s half-Scottish, half-Swiss. All the stuff, in other words, that Fleming put in the canon piecemeal, and I was able to extract it and put it in the novel. He goes to Africa in mine, somewhere he barely visits in the Fleming books; I thought, “That’s a new continent, with no guns and no gadgets, just a man in the jungle.”’

Solo was well received, and Boyd remains proud: ‘It can sit on my shelf in its rightful place alongside any of my other novels.’ Its success, and the resurrections of Bond by such novelists as Anthony Horowitz, Jeffery Deaver and John Gardner, means that the notoriously conservative Fleming estate may yet take a chance on an even more adventurous interpretation of the character. It would be fascinating to see a bestselling female author take on a James Bond novel, exploring and even capitalizing on his flaws and failings, and producing a thoroughly 21st-century secret agent.

It is part of Bond’s continuing appeal that he behaves in ways most of us would never dream of emulating, but still observe enviously. Once this involved traveling the world and beating up nefarious strangers on night trains. Now, the vicarious thrill is watching a toff who smokes and drinks too much. If Ian Fleming could see what has happened to his world, one feels he would be turning in his well-upholstered grave. Let us hope that his creation is never forced into a similarly unbecoming corset of respectability. Bond wouldn’t be Bond if he went full woke. Sally Rooney, lower your weapon; you are not yet required on Her Majesty’s secret service.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2021 World edition.