It’s becoming spooky season, by which I mean not Halloween but elections — at least in Virginia and New Jersey, which have gubernatorial races. They are, incidentally, two of the three states I’ve lived in (I’m in Virginia now; the other one was Maryland).

National elections have ceased to be fun for some time now, and I’m not sure my own state’s gubernatorial race is going to be much better. I’m supposed to choose between a washed-up former governor and a businessman-turned-political-neophyte who enthusiastically hawks his endorsement by the businessman-turned-political-neophyte who last occupied the White House. I’m not excited, although I’m happy enough to see out our current governor, a doctor whose coronavirus policies mostly consisted of aping Maryland’s and Washington DC’s.

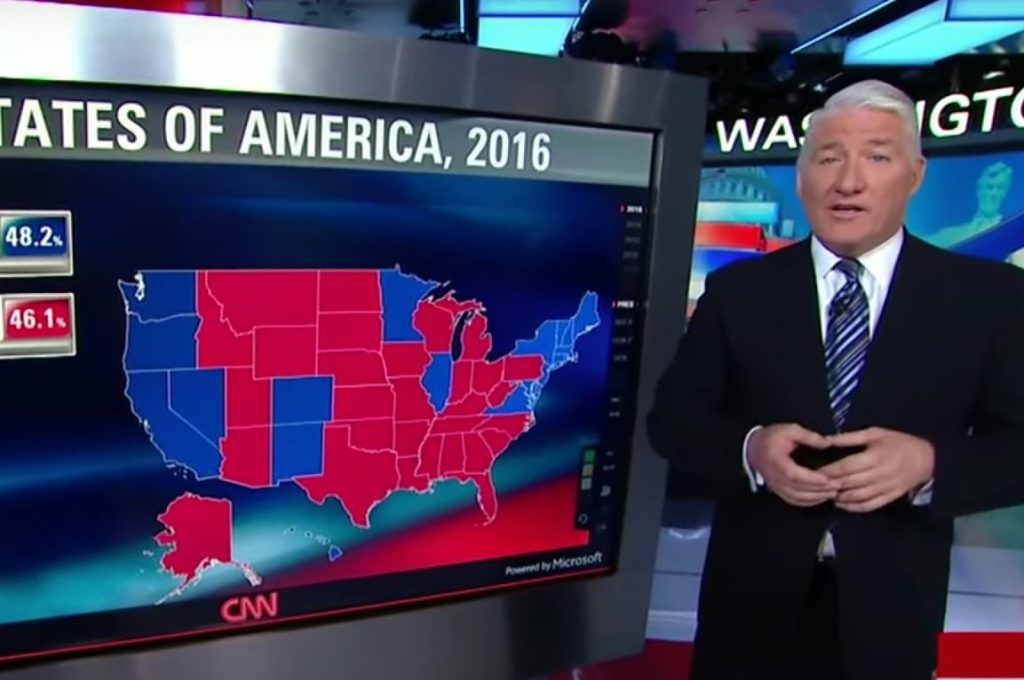

But I’ll still probably watch the results come in on November 2. Because there’s one thing about election night that transcends all the silliness and nastiness, that transcends petty politics and points to something nobler and higher. It’s CNN’s — yes, CNN’s — ‘Magic Wall’, usually operated by chief national correspondent John King. It shows the electoral map, the vote tallies at state and county levels, the county lines, voters by demographic, urban-rural political dynamics, and much more.

Most fascinating to me is the almost ritualistic invocation of various bellwether and swing counties, as well as many more obscure ones. Ashtabula. Macomb. Kent. DeKalb. Nash. Luzerne. Many of them in the sparsely populated rural areas of states that I only know as names on a map. It’s almost mesmerizing. Election nights are about the only time the American public sees, and is really made to grasp, the whole United States in both its massiveness and its granularity.

These segments always inspire a certain kind of patriotism. Not the shallow, emotional, flag-waving and flyover variety, but a genuine, literal patriotism: a deep appreciation for this land. This, importantly, is not nativism or nationalism either. ‘Blood and soil’ is itself an ideological abstraction; the land under my feet is not. And it belongs not to any one demographic, but to everyone represented by that map, in every nook and cranny of the country.

Those endless counties, and the strangeness with which electoral wins and losses play out, can be frustrating, but they don’t have to represent or foment division; quite the opposite. This is one of those quirky, distinctive, sometimes infuriating aspects of American democracy. Isn’t it kind of amazing that our elections often turn on a handful of not particularly distinguished places that most Americans will never visit and that many have never heard of? Isn’t it so American, in every good and bad and complicated way, that such ordinary people and places are bestowed with this kind of power? Isn’t that something to safeguard and cherish?

It’s true that America’s elites and experts leave something to be desired, from the long disaster of the ‘war on terror’ to the bipartisan bungling of the pandemic. Income inequality is an issue. Our built environment, housing markets, and land use need plenty of work. Toxic partisanship rises and political violence looms. Our country has problems, some very serious.

But as long as Detroit and North Dakota and rural Kansas and suburban Philadelphia matter, and as long as they have their place in the sun every four years, our democracy is healthier, stronger, and more decent than it might look otherwise.

Addison Del Mastro writes on urbanism and cultural history. Find him on Substack (The Deleted Scenes).