You may think you have experienced buyer’s remorse. But until you’ve splashed out $5,000 on a Jpeg, you have not. That’s where I found myself the other day, after an adrenaline-fueled afternoon bidding on a digital collectible ‘card’ depicting the Mona Lisa sitting on an easel.

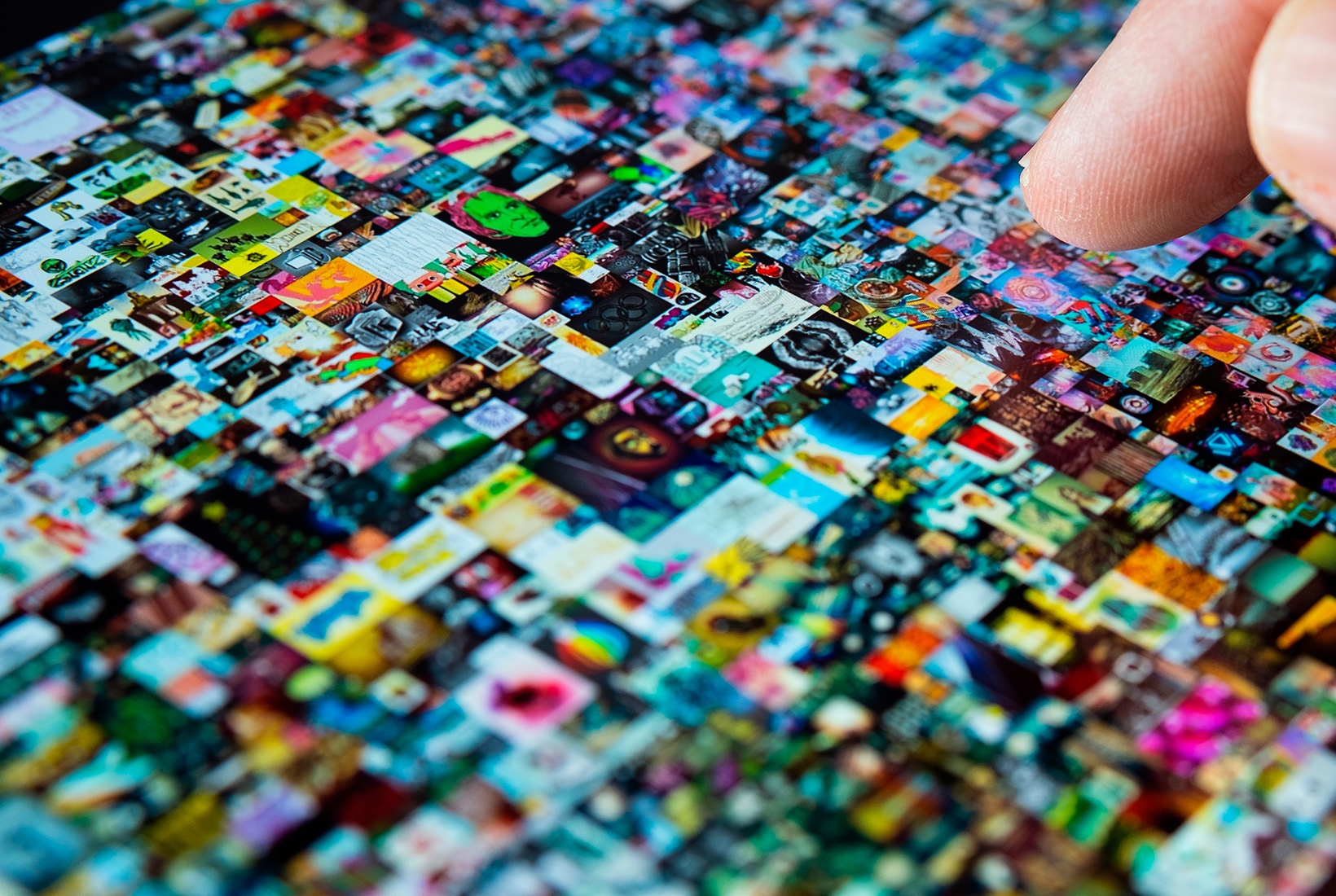

The item in question is a Curio Card, one of the earliest examples of a non-fungible token (NFT), a new technology used to buy and sell digital art. NFTs are the latest frontier for crypto-currency maniacs, the online gold rushers who keep financial watchdogs awake at night. Bored by a quiet summer for stock markets, memes and bitcoin speculation, the maniacs are piling into the fledgling digital-art market.

It is booming. In August, punters spent a total of $2 billion on NFTs. Some of the sales are truly farcical, like the clip-art image of a rock which went for $1.3 million. Last week a woman called Natasha Che bought a diamond for $5,000, destroyed it, then flogged a photo of it for $18,000. There’s been a slight lull in NFT mania in recent days, as crypto-currencies dipped. But the overall trend is up and up.

If you’re still wondering what the hell I’m talking about, let me try to explain. An NFT is an ownership record of something unique, like a digital painting. If you buy it, you are the sole owner of the artwork. Of course, on the internet, you can just right click and save the file. But you would own a reproduction, not the original. To put it in terms of physical art collecting: anyone can have a Van Gogh print; only one person can own the original.

Not that we’re talking Van Gogh here. Most NFT art looks like something a 14-year-old would draw on their pencil case while high on Monster energy drinks. Among the most valuable collections you’ll find cartoons of apes, aliens and mutants.

The punters seem to appreciate this comic-book aesthetic. It’s high art for the geek universe. Still, most are in the game for more mercenary reasons. As in crypto speculation, almost all the chatter from the ‘community’ is blind get-rich-quick evangelism.

It’s all a suitably absurd craze, very in keeping with the past two years, which have seen so many ludicrous financial fads that it is now a cliché to say we are in a bubble.

The boom certainly won’t last, and my involvement in it is closer to gambling than the sober business of tending to a portfolio. This week, while attempting to buy a new ‘Sneaky Vampire’, I was struck by the similarities between NFTs and slot machines: long odds of success, a nervous wait and the familiar bout of self-loathing, then in the end a cartoon vampire tells you if you’ve won a cash prize.

Despite all the above, I’m still a believer in NFTs. Increasingly we live in the digital world. In the next 30 years, we will spend more time in shared virtual spaces, the so-called metaverse. We will buy stuff for that world.

It’s early days, but people are already spending money on virtual goods and experiences. The wildly popular game Fortnite hosted a temporary Martin Luther King experience the other week. An adult friend recently confessed to paying £100 for a beret and some leather pants for his character in the action video game Call of Duty. He had to throw out the pants after his teammates complained they squeaked when he walked, giving away his position.

In this brave new world, the rich will decorate their virtual homes with attractive art and status symbols. That’s what’s driving the huge prices for NFTs at the moment: they’re the perfect signal that you were an early adopter. Meanwhile, back in the real world, the technology will become so good for hanging digital art on your walls that an NFT painting will look and even feel like a painted canvas. For the moment, though, we’re stuck with hideous cartoons you can’t hang anywhere except your Twitter profile.

That hasn’t stopped some big names piling in. Visa sparked a late-summer market surge after it bought a CryptoPunk (one of the first ever NFTs) for $150,000. Christie’s and Sotheby’s smelled the cash early and are holding another series of auctions this month which are likely to drive up prices.

Damien Hirst, never one to miss out on a bit of cash, has his own grift, appropriately called The Currency. He produced 10,000 almost identical but just about unique dot paintings, selling them for $2,000 each. The twist: buyers have a year to decide whether to keep the physical painting or the NFT, and Hirst burns the one they don’t choose.

The Damiens were my gateway drug to NFTs — I bought one assuming I would take the physical painting, but then watched the price of the digital versions soar to $60,000. They have since fallen to half that peak, but I’d seen enough to drink the Kool-Aid, and I look forward to the sweet scent of burning canvas in July 2022.

Soon I was scouring for more opportunities. I eventually settled on the Mona Lisa Curio Card (whose official title is ‘Painting’). I persuaded a friend to go halves with me. Not only is it one of the first ever NFTs, we told ourselves, it is the first depicting a woman. A full set of Curios is going on auction at Christie’s on October 1, including our Mona as the poster girl for the exhibition.

We piled in, then I flicked open a new tab to browse which Notting Hill town houses I might snap up with my inevitable winnings. One hour later the price was up; we’d made a grand. Then it tanked. Turns out we bought at the top of the market, and my pal and I are currently nursing a loss of 50 percent. We could face a decade of holding on until our valuable piece of internet history gets the recognition it deserves. Either that or it will prove utterly worthless.

That’s the problem with NFTs. As with the dotcom bubble, there are probably a few winners lurking among a steaming pile of overvalued turds. The challenge is telling them apart. In the meantime, I am open to offers for the NFT of this article.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.