Over the past six decades Homo sapiens occidens has grown progressively more informal in matters of clothes, language, speech, manners and social behavior to the point where, having lost any form whatever, it has devolved into Homo slobus, and democracy into slobocracy. This departure from formality has occurred across every class of society and every occupational and social category — politics, corporate business and finance largely excepted — including what remains of high society, private schools and clubs, and the churches. The lockdowns that followed from the pandemic contributed immeasurably to an already precipitous momentum. The popular majority, its male half especially, views the process as yet another form of personal liberation from outmoded social constraints and a triumph for self-expression.

Here personal convenience and innate sloth have conveniently converged with the ideologically driven, highly self-conscious and largely superficial democratization of Western society being promoted today by a meritocratic elite that hopes to forestall the envy of the mob below it by pretending to believe in, while honoring rhetorically, the ideal of democratic equality. Aristocracies of the past have always emphasized the importance of formality not only for themselves but for the inferior classes as well. What aristocratical form, institutional order, the churches and social constraints the hierarchical state provides, democratic society must impose on itself.

In the absence of formal society and social forms, democracies depend upon three agencies to hold them intact and give them direction and momentum. One is an honest and efficient political system; the second a coherent body of law whose spirit, as Montesquieu said, is the also the historical spirit of the nation; the third organized or established religion. Politics take their character from society and religion, and the law reflects all three. Hence a society lacking the particular form that can only be acquired by embracing and adhering to certain formalities is condemned to formlessness in its political, legal, and social systems — in other words, to the formlessness and inarticulation that is tyranny. Under tyranny, the government and the government alone has shape, form and active articulated parts; society itself remains a single unified and paralyzed mass.

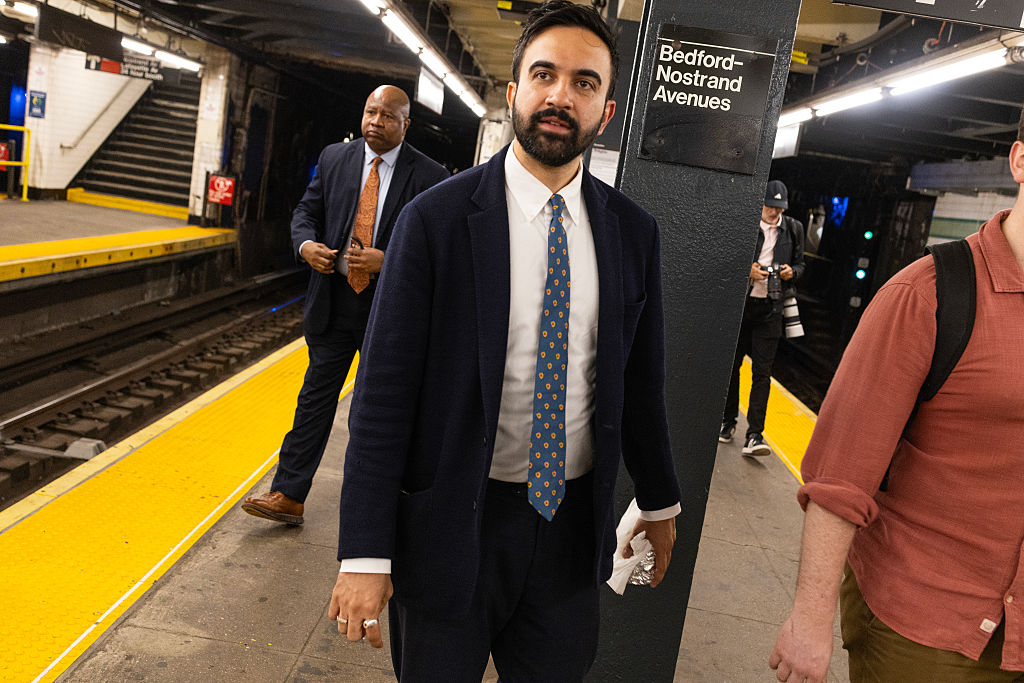

As I say, the exaggerated and humanly unnatural informality of Western society today is due in part to natural human laziness combined with the demotic indifference to the normal demands of personal pride that postmodern democracy encourages, and to the pretense by politicians and the ruling class that we are living in a classless system, even as society becomes, year by year, more stratified according to levels of education, wealth, and political power — a too-obvious reality that the social regularization of informality and the lax acceptance of swinishness are meant to obscure.

Beyond its fundamental and essential importance to democratic society, formality has further advantages and benefits that are being rediscovered as the pandemic retreats and the world of work and the daily routine returns to replace it. After having allowed those members of their staffs whose jobs made it feasible to work from home in slippers and pajamas for the past eighteen months, business executives are reassessing the importance of formality in dress as the prospect of previously remote employees returning to the office nears. Self-employed people such as writers, composers, artists and architects who have spent their lives working chez eux have always understood the importance of maintaining a proper office there, of dressing neatly each morning and adhering strictly to a self-imposed daily schedule. In the less informal past, many of them actually did dress in coats and ties or dresses at the desk, piano or drafting board, as if for the office. Formality is a mental discipline as well as a social, business and professional convention that encourages a sense that one is engaged in dignified and important work. An office setting promotes the same confidence in one’s colleagues, while discouraging the intellectual and emotional laxness that promotes an overly social and relaxed atmosphere. Above all, formality at each level of society and in every social venue, in business and in government is an indispensable source and preserver of morale, in all societies without exception but in democratic ones especially.

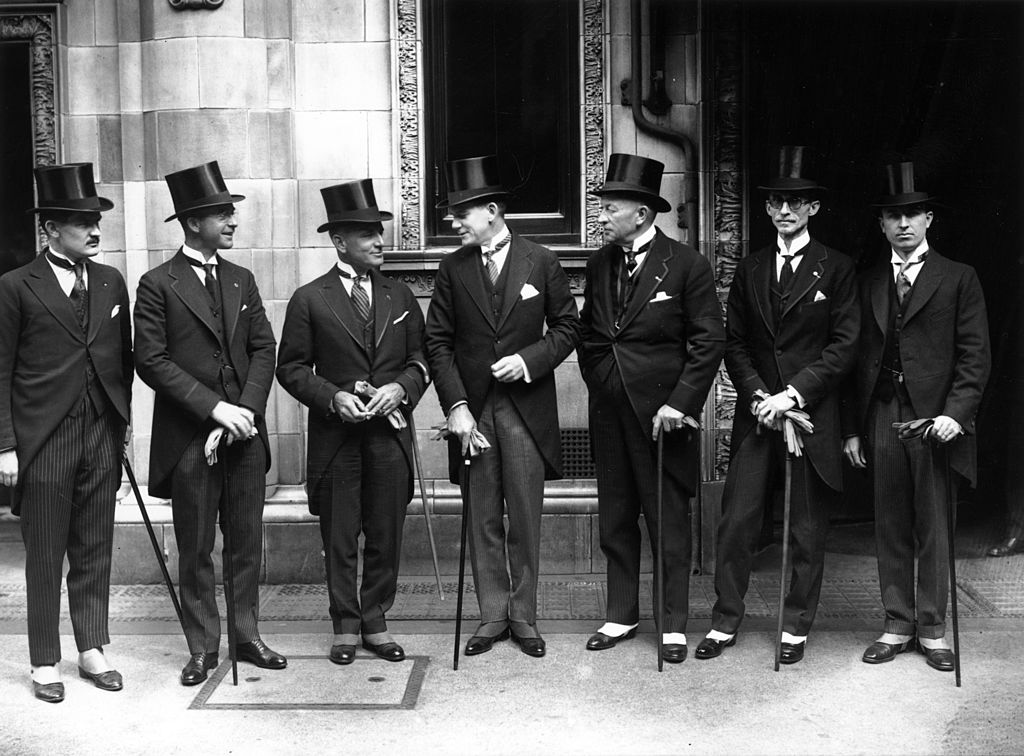

Nor should the pleasures of formality, in dress especially but also in manners, be overlooked. Women appreciate these things and take enjoyment from them, while until the day before yesterday men of every culture and class, from African warriors to Sicilian peasants and aficionados of the corrida to box holders at Covent Garden and the Metropolitan Opera, used to do. Not so many years ago, the stands at Yankee Stadium were crowded by men in business suits, neckties and fedoras. (In my youth, my classmates and I vied with one another in adding personalized adornments to the school uniform — French and Italian ties, elegant lapel pins — and competed in jack-cleaning week for the most elegant sport coat.) Western democratic people — including, alas, many women — must be the first human beings in the history of the world to dress to look their worst rather than their best on important occasions as well as ordinary ones. For the past couple of decades the waiters at the most expensive restaurants in the world have been worse dressed by far than their wealthy patrons, who appear insensible of the pleasure and satisfaction of eating a fine meal in an elegant room and in elegant dress, while seeing and being seen by one’s fellow diners similarly attired. As for religion, arguments about ritualistic standards and practices are pointless when congregations appear in church for divine service — including funerals — in shorts, T-shirts and sneakers.

Perhaps the time is not far off when the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace and Trooping the Colour will be enacted by soldiers in Levis, tank tops and ball caps. If so, it will mean an end to the British Monarchy, the United Kingdom, and with them the awe and delight taken by the spectators — plain democratic citizens most of them — crowded against the Palace Gates and assembled in ranks along Constitution Hill.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2021 World edition.