This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.

The American experiment is fragile. It has always been fragile and always will be fragile because it is so extremely unnatural. ‘Unnatural’ in this context means in conflict with human nature. Jonah Goldberg has described the fragility of the American system by comparing it to a garden hacked out of a tropical jungle. A garden surrounded by jungle is unnatural. The gardeners must tend it with unremitting care lest the jungle return.

Treating our fellow human beings as individuals instead of treating them as members of groups is unnatural. Our brains evolved to think of people as members of groups; to trust and care for people who are like us and to be suspicious of people who are unlike us. Those traits had great survival value for human beings throughout millions of years of evolution. People who were trusting of outsiders were less likely to pass on their genes than people who were suspicious of them. People who were loyal to their tribe were more likely to pass on their genes than people who stood apart.

The invention of agriculture and the consequent rise of complex societies exposed another aspect of human nature that had enjoyed less scope for expression in hunter-gatherer bands: acquisitiveness, whether of money, status or power. Whatever its evolutionary roots may be, the empirical consistency of human acquisitiveness over the eons is impressive. The open-ended desire for more money, status or power has been natural; to voluntarily limit one’s wealth, status or power has been unnatural.

The combination of acquisitiveness and loyalty to the interests of one’s own group (be it defined by ethnicity or class) shaped human governments for the subsequent 10,000 years. The natural form of government was hierarchical, run by a dominant group that arranged affairs to its benefit and oppressed outsiders to a lesser or greater degree, usually greater. The rare attempts to try any other form of government were unstable and short-lived. The American founders’ idealism lay in their belief that an alternative was possible. Their genius was to design a system with multiple safeguards against the forces that had made previous attempts self-destruct.

America proved that a durable alternative to the natural form of government was possible — a constitutional republic combined with carefully circumscribed democracy. The idea behind that alternative eventually spread around the world, but neither the United States nor any other country that has made it work has ever been out of danger. If we decide that our system for tending the garden needs to be replaced, and if the replacement should prove to be even slightly less devoted to keeping nature at bay, the garden will be reclaimed by jungle within a few decades.

The introduction of identity politics into that carefully crafted constitutional system does not simply distract us from warding off the jungle. It is the jungle, the primitive sense of ‘us against them’ pressing in upon the garden. It not only permits but insists that the power of the state be used to reward favored groups at the expense of everyone else. That view of power is the defining characteristic of the natural form of government that humankind endured until the miracle at Philadelphia in 1787.

Many of you were taught about the fragility of democracy in your first high-school civics course and don’t have difficulty accepting the analogy of the garden. But I am sure that many of you also have come to this page unconvinced that the facts of group differences are as important as I have claimed. I suggest that a reason for such a reaction is grounded in another aspect of human nature: the impulse to generalize from our own experience even when we know intellectually that our experience is not representative.

Suppose that your personal experience has consisted of life as a white in an upper-middle-class American suburb. Your black, Latino and Asian neighbors have been as smart, engaging and helpful as your white neighbors. The bell curve of your personal experience does not involve mean differences in cognitive ability or crime rates. It is natural to think your experience invalidates the data about group differences in means.

The mind insists on generalizing. But when mean differences between groups are real, it is absolutely essential to resist generalization; it is essential to accept the reality of documented group differences but to insist on thinking of and treating every person as an individual.

Why? After all, even if you’re technically ‘making a mistake’ with your generalization, it’s on the side of generosity and optimism. How could that be bad? The answer is that if it’s OK for you to do it, it’s OK for everyone else to do it. That way lies unrestrained racism.

Suppose that instead of living in an upper-middle-class suburb you are a white living in a multiracial working-class or middle-class neighborhood in a megalopolis. The great majority of crimes are committed by minorities. Most of the children in the bottom of the class in your child’s school are minorities. These observations are not the products of a racist imagination. They are the facts of your lived experience. There are exceptions, to be sure — your daughter’s super-smart minority classmate, the minority couple down the street who provide loving care for foster children, the minority cop you watched deftly defuse an escalating confrontation. But your lived experience tells you that these are not typical. Is it OK for you to generalize that minorities are criminal and dumb? Obviously not. The obviously correct answer is that a difference in means exists, but that we must insist on treating people as individuals.

If you agree that it’s wrong for whites living in a multiracial working-class or middle-class neighborhood to generalize from their experience but think that it’s still OK for whites in an affluent neighborhood to do so, then I ask that you take two other considerations on board:

- Advocating double standards for people on top and everyone else is a bad idea

- A lot more whites live in working-class and middle-class neighborhoods than in affluent ones

These two considerations are politically pragmatic. The elites who run the country would arouse much less hostility if they kept both at the front of their minds.

The truly grave danger of refusing to confront race differences in means is that it leads in a straight line to thinking that the only legitimate evidence of a non-racist society is equal outcomes. It appears that the Biden administration already accepts that logic. If that’s what the people in power truly believe, and if those equal outcomes continue to elude them, the logical conclusion is that the state must force equal outcomes by whatever means necessary. Once the state is granted the power to engineer equal outcomes by dispensing opportunities preferentially and freedoms selectively, it will be one group versus another, ‘us’ against ‘them’. The garden will give way to jungle.

***

This essay is adapted from Charles Murray’s Facing Reality: Two Truths About Race in America (Encounter, $26).

***

People on the left understand the danger to the nation posed by those on the far right who applaud violence and racism. People on the right understand the danger to the nation posed by those on the far left who insist that whites are irredeemably racist. But we need everyone to understand that what keeps us all safe is the state’s impartiality. The nation’s commitment to impartiality has been eroding for decades. The most threatening development of all is that whites increasingly seem to agree that identity politics is the way to go.

In retrospect, President Obama’s eight years in office look like a prolonged inflection point for race relations. In 2001, Gallup’s pollsters began asking the question, ‘Would you say relations between whites and blacks are very good, somewhat good, somewhat bad, or very bad.’ Seventy percent of whites and 62 percent of blacks answered that they were either ‘very good’ or ‘somewhat good’. When Barack Obama was elected in 2008, those numbers were almost the same: 70 percent and 61 percent respectively. During his first term, they improved slightly, standing at 72 percent and 66 percent in 2013.

When Gallup next asked the question about race relations just two years later, the number for whites who thought that relations were ‘very good’ or ‘somewhat good’ had fallen off a cliff, from 71 to 45 percent. The black number had dropped from 66 to 51 percent. During the Trump years, the white number stabilized — it was 46 percent in 2020 — but the black number fell to 36 percent. In just seven years, Americans’ perceptions of race relationships had gone from solidly optimistic to solidly pessimistic.

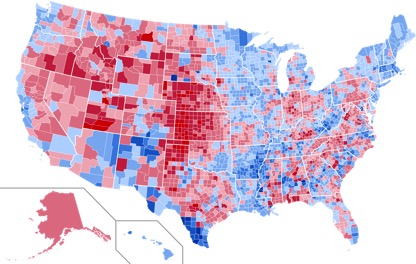

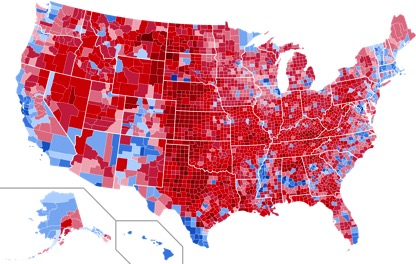

During that time, race also become more closely tied to the nation’s political divisions. You have probably seen electoral maps similar to the pair below, but it’s worth your time to contemplate them in light of the material I’ve presented. They are the 1996 and 2016 presidential electoral maps. The units in the maps are counties. The darker the color, the bigger the margin for the Democratic or Republican candidate (blue and red respectively).

When Bill Clinton won a second term in 1996, the electoral map of counties was a mix of red and blue shades, mostly pale on both sides. The deep red counties were confined largely to Bob Dole’s home state, Kansas, and its neighbors. The blue counties showed no obvious correspondence with racial composition — some of them were in counties with large minority populations, but even more of them were in counties where whites constituted more than 80 percent of the population.

***

Subscribe to The Spectator’s World edition here

***

Just four years later, the county map of the 2000 election already showed the basic shape of the coming polarization — blue on the coasts, red in between, but less starkly divided and with mostly pale shades of red and blue. By 2016, the interior of the country was overwhelmingly red. The remaining blue counties in the Mountain West were those with large populations of Amerindians. The blue counties in the South were ones with large black populations. The blue counties in the Southwest were ones with large Latino populations. Outside big-city America, white America had become landslide-red Republican.

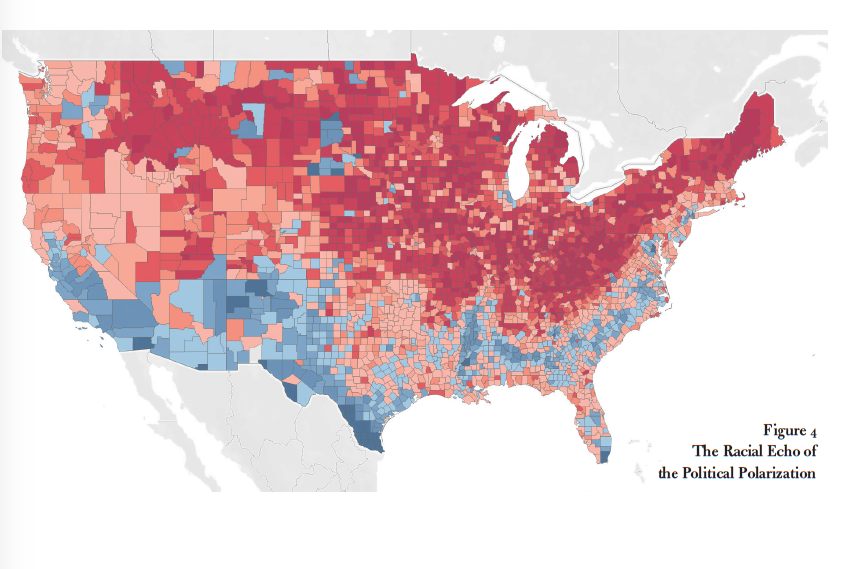

Much of that change had nothing to do with race relations or identity politics, but with the alienation of middle-class and working-class whites from the coastal elites. I have written about that alienation at length. But if identity politics did not start the change, it had become part of it. Compare the two electoral maps above with the one below. It is also based on counties. Red counties are ones in which at least 50 percent of the population is white. The darker the red, the higher the percentage. Blue counties are ones in which whites are not a majority. The darker the blue, the higher the percentage of minorities.

This map looks strikingly similar to the map of the 2016 presidential election. The main difference is that light pink counties in this race-based map are often dark red counties in the election map. The polarization continued during the Trump years. The 2020 map is almost indistinguishable from the 2016 map despite the different electoral outcome.

Perhaps the deepening polarization would have continued just because of the alienation between elites on the coasts and the people who live between them. But it is also plausible that the alienation between blacks and whites played a role. Purely on grounds of expediency, the rhetoric about white privilege and systemic racism coming from black opinion leaders has always seemed borderline suicidal. Blacks, constituting 13 percent of the population, are telling whites, 60 percent of the population, that they are racist, bad people, the cause of blacks’ problems, and they had better change their ways or else. Right or wrong, that rhetoric has been guaranteed to produce backlash by some portion of the 60 percent against the 13 percent. So far, this effect has been masked because the strategy has worked so well with white elites. Ordinarily, you can’t insult people into agreeing with you, but white guilt is a real thing. In the summer of 2020, many white college students and young adults agreed that they had sinned, even though they hadn’t realized it until now, and joined in Black Lives Matter marches. The New York Times, the Washington Post, NPR, PBS, CBS, NBC, ABC, CNN and MSNBC gave sympathetic coverage to the protests and, to varying degrees, downplayed the riots and looting.

Meanwhile, many middle-class and working-class whites have not been insulted into agreement. They’re just insulted, and to their minds unfairly insulted. I’m not talking about white nationalists and white supremacists — their numbers are relatively small. My concern is the extremely large majority of middle-class and working-class whites who don’t think of themselves as racists and have not behaved as racists.

Tens of millions of these people live in towns that have no black residents or just a few, and racial issues haven’t impinged on their lives. They don’t understand why they are being accused of racism. Still other tens of millions live in large cities where racial problems have been real, but they see themselves as having treated black and Latino neighbors and coworkers with friendship and respect. They believe that everyone has a God-given right to be treated equally. Now all of them are being told that they are privileged and racist, and they are asking on what grounds. They are living ordinary lives, with average incomes, working hard to make ends meet. They can’t see what ‘white privilege’ they have ever enjoyed. Some are fed up and ready to push back.

How widespread might the backlash be? It is one of those topics that the elite media has been unable to investigate more than superficially. But it seems beyond dispute that a growing number of whites are disposed to adopt identity politics — to become a racial interest group in the same way that blacks and Latinos are racial interest groups.

The question asks itself: if a minority consisting of 13 percent of the population can generate as much political energy and solidarity as America’s blacks have, what happens when a large proportion of the 60 percent of the population that is white begins to use the same playbook? I could spin out a variety of scenarios, but I don’t have confidence in any of them. I am certain of only two things.

First, the white backlash is occurring in the context of long-term erosion in the federal government’s legitimacy. Since 1958, the Gallup polling organization has periodically asked Americans how much they trust the federal government to do what is right. In 1958, 73 percent said ‘always’ or ‘most of the time’. Trust hit its high point in 1964, when that figure stood at 77 percent. Then it began to fall. By 1980, only 27 percent trusted the government to do what is right. That percentage rebounded to the low forties during the Reagan years, then fell to a new low, 19 percent, in 1994. It rebounded again, hitting a short-lived high of 54 percent just after 9/11. Then it plunged again, hitting another new low, 15 percent, in 2011. It has been in the 15- to 20 percent range ever since. A government that is distrusted by more than 80 percent of the citizens has a bipartisan legitimacy problem.

When a government loses legitimacy, it loses some of the allegiance of its citizens. That weakened allegiance means, among other things, a greater willingness to ignore the law. The federal government has enacted thousands of laws and regulations. Many of them apply to every family and every business in the nation. They cannot possibly be enforced by the police or courts without almost universal voluntary compliance. When a government is seen as legitimate, most citizens voluntarily comply because it is part of being a citizen; they don’t agree with every law and regulation, but they believe it is their duty as citizens to respect them. When instead people see laws and regulations as products of the illegitimate use of power, the sense of obligation ends.

Events since the summer of 2020 make me think it is too late to talk about if whites adopt identity politics. Many already have. That’s the parsimonious way to interpret the red-blue divisions over wearing masks, the widespread belief in red states that the 2020 election was stolen, and the rage that resulted in the invasion of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. This is all evidence that the federal government has lost its legitimacy in the eyes of many whites. If that reaction spreads, the continued ability of the federal government to enforce its edicts in the reddest portions of the nation will be thrown into question. The prospect of legal secession may be remote, but the prospect of reduced governability from Washington is not.

The second thing of which I am certain is that Donald Trump’s election and the lessons of his term in office changed the parameters of what is politically possible in America. Someone can win the presidency without having been a governor, a senator, or a general. Someone can win it without any experience in public service at all and without any other relevant experience. Someone can win with a populist agenda. Someone can govern without observing any of the norms of presidential behavior.

Those lessons have not been lost on the politically ambitious of either the left or the right. All over the country, people at the outset of their political careers see a new set of possibilities. They include many who are as indifferent to precedent and self-restraint as Donald Trump was and who are more serious students of the uses of power than Trump was. It is increasingly possible that, the next time around, someone who is far more adept than Donald Trump can govern by ignoring inconvenient portions of the Constitution.

This essay is adapted from Charles Murray’s Facing Reality: Two Truths About Race in America (Encounter, $26). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.