Years after my mother and I left China, I found out the real reason why. A neighbor had reported my mother for being pregnant with her second child. She was paid a visit by local officials who gave her a choice: she could either take herself to the abortion clinic or they’d take her there themselves. She chose a third option: to move to London to join her husband, who was working in the UK. In August 2004, when six months pregnant, she left her family and friends behind in Nanjing. My brother was born later that year in Kingston Hospital.

Other families weren’t so lucky. Beijing demographers were concerned that food production would not keep up with population growth. And it wasn’t just the Chinese who were worried. The West was fixated on the world’s ‘population bomb’ and China was seen as being at the epicenter of it. When Deng Xiaoping introduced the one-child policy in 1980, the Washington Post congratulated him for averting catastrophe.

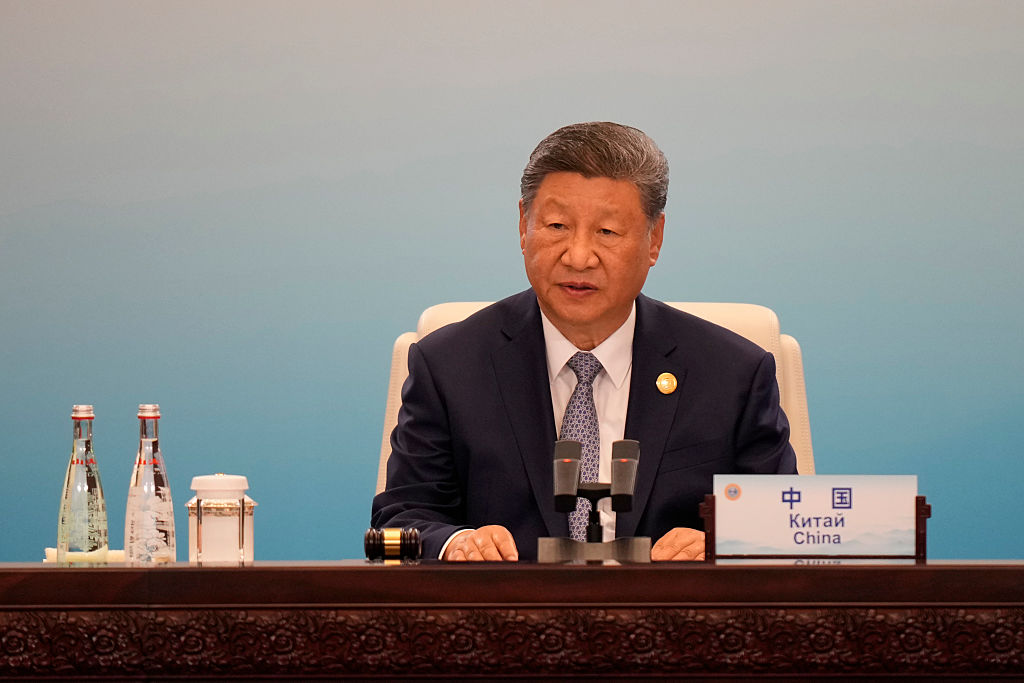

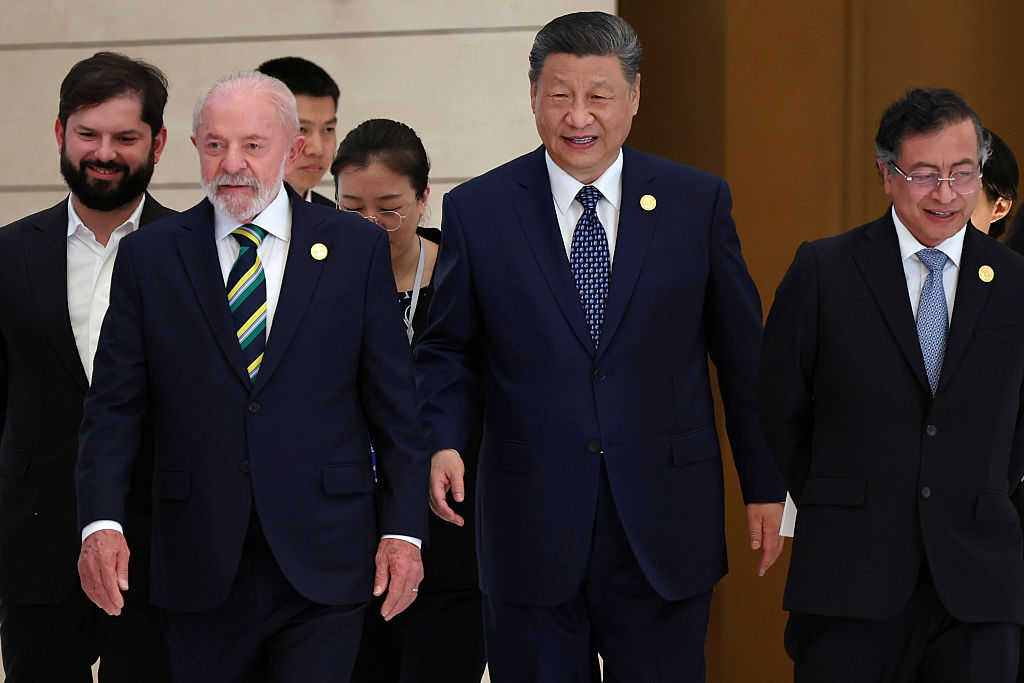

Now, though, there’s a new panic. In 1970, the average Chinese woman had six children; today she has 1.3, way below the 2.1 needed for population replacement. Before long, perhaps in this decade, China’s population is expected to peak, then enter permanent decline. Beijing has realized its consumption-led, labor-fueled economic growth is at risk of becoming a thing of the past.

This is why the one-child policy was abolished five years ago, with the allowance increasing to two. But the birth rate has remained stubbornly low. Last year, the number of new births was at the lowest level since the Great Famine in 1961. This week, Beijing announced married couples are now permitted to have three children.

It might be too little, too late. Hundreds of millions of Chinese children have no siblings. Brothers and sisters were something we saw on dubbed American sitcoms, as foreign and exotic as blue eyes and blonde hair. I grew up thinking that it simply wasn’t Chinese to have more than one child. Many of my generation don’t yearn for a big family, because it’s something we have never experienced. And for the most educated female generation in Chinese history, there is more to modern life than motherhood.

What’s more, raising children in China is extortionate. New parents do not face the problems their grandparents faced: going hungry; the Cultural Revolution. But huge economic growth brings its own issues. In China, the state education sector is small, so just over a third of children are privately educated. School fees are expensive — not to mention the English and math tutoring; the music and dance lessons; all the sports clubs. For middle-class parents, there is immense social pressure to compete with each other. And now times that by three?

Work life is also relentless. The notorious ‘996’ regime, which refers to ‘9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week’, is spreading from China’s tech sector to other white-collar industries. It’s hardly a family-friendly life.

So instead of welcoming this week’s news, Chinese social media exploded in rage. ‘Giving birth is not the problem, bringing them up is!’ one user fumed on Weibo. ‘996 is the best contraceptive,’ said another.

The one-child experiment has led to strange family structures. Most millennials have two aging parents and four grandparents, which creates an inverted pyramid of elderly people who need care. Care homes are still frowned upon. As long as you can earn, you’re expected to look after your own family. But by 2050, it’s estimated that two in five Chinese people will be retired. Life expectancies are also increasing. Many would-be parents complain they are too worried about looking after elderly dependents to think about adding children to the mix.

The tragedy is that in the early days of China’s economic boom, those who wanted more children and could afford it (like my mother) were not allowed to have them. It’s now too late for many of these women. But for young couples, who are expected to re-invigorate the economy, the costs and pressures of modern life preclude a big family.

The Politburo has made promises to reduce school fees, improve maternity leave conditions and safeguard women’s roles in the workplace. But there has been no mention of working hours, or affordable housing.

When change comes in China, it comes fast. In my brother’s short lifespan, there has been a 180-degree turn. After decades of seeing children as the problem, Chinese politicians have a new message: procreation is patriotism. The problem is that many Chinese people disagree.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.