In October last year Emmanuel Macron had a long list of around 300 to 500 names drawn up. These were no ordinary figures but rather a number of renowned French immigrants who were being lined up as candidates for new street names and statues. Among their number was Martinican philosopher and activist Frantz Fanon, Moroccan war veteran Hammou Moussik, and the Egyptian French singer Dalida. And yet the man behind the scheme, Pascal Blanchard, is arguably more interesting than any of the names on the list.

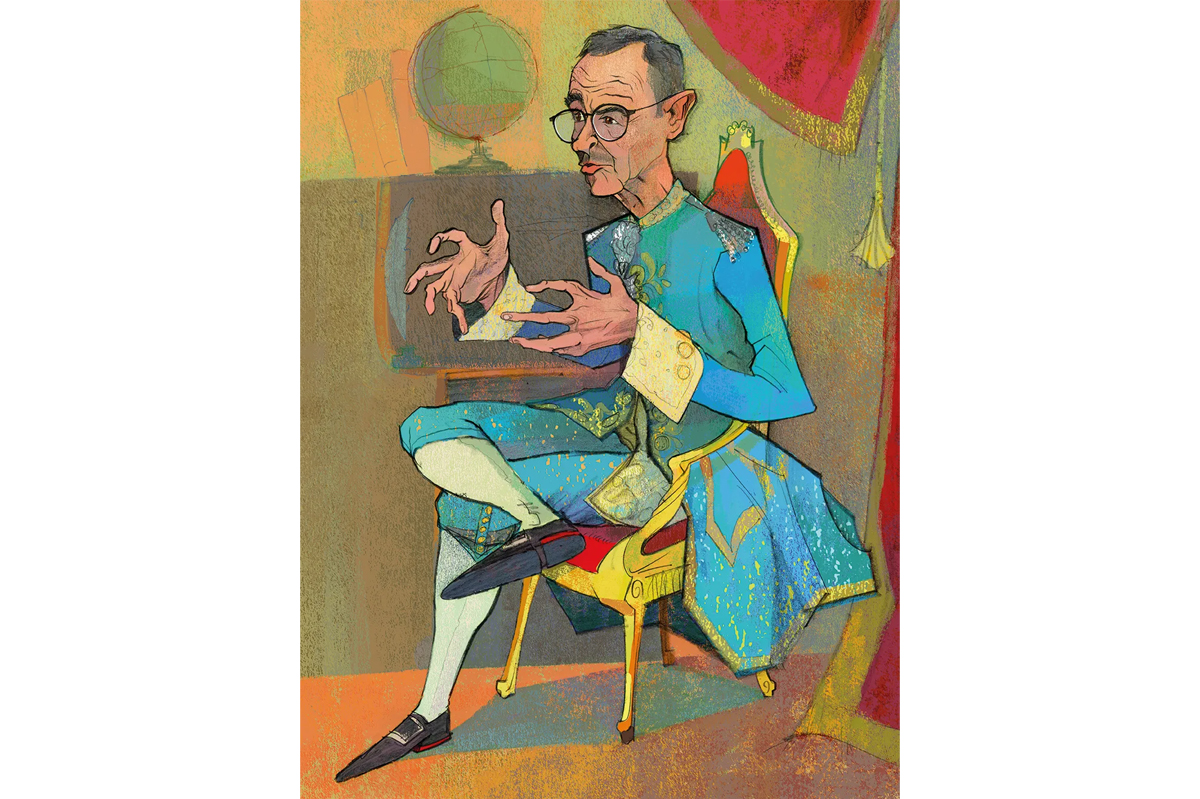

The so-called Rasputin of Macron’s inner-circle, Blanchard is thought to be the driving force behind President Macron’s postcolonial initiative, whispering into his ear during private meetings and film-screenings at the Elysée while officially sitting at the head of the diversity committee. A self-styled historian linked to the Committee National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Blanchard runs several businesses as well, notably his communications consultancy, Les Batisseurs de Mémoire that promises to deliver ‘pedagogical support’ to organizations and businesses negotiating their postcolonial messaging. On their website the company promises to verify the ‘historical accuracy’ of the colonial past.

All French presidents have advisers, official or otherwise (consider Mitterand and his army of spies) but Blanchard is a curious character who ruffles the establishment’s feathers and brows. Historians of the French Academy such as Bernard Rougier have denounced Blanchard as a phony and a fake, whose supposed interest in postcolonial affairs acts as nothing more than a cover for his business ambitions. Others at the Sorbonne mutter that his academic credentials are suspect, pointing out that he has never held a position at any university despite his curiously renewed status as ‘researcher’ at CNRS. Of the many epithets used to describe him — bonimenteur (peddler), marchand de mémoire (memory flogger), voyeur postcolonial (postcolonial voyeur) — the most damning is surely ‘Rastignac’, a reference to Balzac’s social-climbing arriviste in the Comédie Humaine. That such a term is the most grievous insult possible tells you a great deal about the establishment to which Blanchard is laying siege.

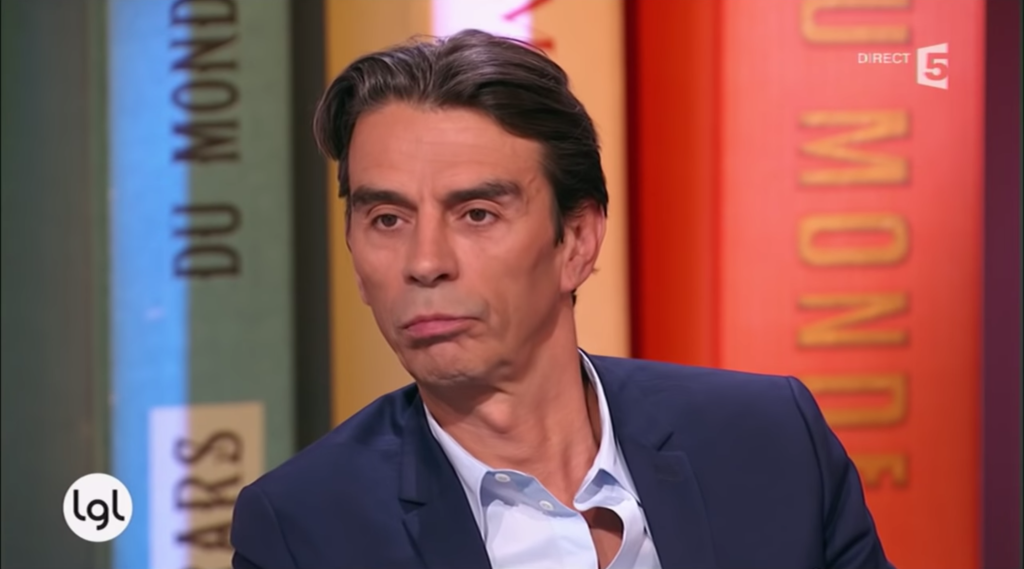

Blanchard, who is 56, with Gallic dark hair swept back and a sharp face, has inveigled his way to the top by limiting his scope to one single issue, over which he commands total authority: diversity. Even his most ardent critics would have to admit his form in this department. He is the author and contributor to dozens of books on the topic including the highly controversial Human Zoos, which argued that the imprisonment of exotic individuals for spectacle during the colonial era is still ongoing in the West today in the form of immigrant ghettos. Blanchard has made it his business to be in the middle of the identity debate that has raged across France for decades.

From the Nineties onwards Blanchard understood, with piercing ideological and business acumen, how ‘race’, ‘heritage’ and ‘colonization’ would dominate the public debate and has turned them to his advantage. When the stakes became higher in 2005 and the Paris suburbs erupted into violence, Blanchard placed himself in the eye of the storm, arguing in his book The Colonial Fracture that the riots were an ongoing symptom of France’s colonial past. Outrage ensued, with commentators claiming that Blanchard had fanned the flames of immigrant resentment for his own gain.

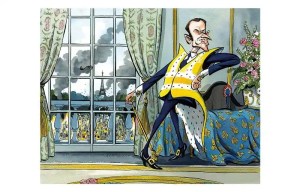

The febrile nature of the French political climate in the middle of a pandemic and in the run-up to a presidential election has allowed figures such as Blanchard to rise in power and gain the president’s ear. Blanchard is also behind the plans to create a museum of ‘colonization’ in France modeled on the one in Washington, a scheme he may well pull off as a member of Macron’s preferred social-liberal think-tank ‘Gracques’.

Although France has a long history of intellectuals becoming intertwined in government (think Bernard-Henri Levy’s involvement in Sarkozy’s 2011 military intervention in Libya), the commercial nature of Blanchard’s endeavors raises alarm bells. As Macron walks the thin line between appeasing the French right and cementing his own centrist stance in the culture wars, it might be easy to see Blanchard as the embodiment of a certain left-turn in France. But to do so ignores the fact that Blanchard has angered scholars within his own camp who claim that his readings of the past are in contempt of the facts. Blanchard’s willingness to appear on television points, they say, to his glaring narcissism rather than his concern for the Republic.

There are, inevitably, comparisons with the British PM Boris Johnson’s advisers. Take Nimco Ali, reportedly godmother to Wilfred Johnson and close friend of Carrie Symonds. Her authority on the subject of female genital mutilation elevates her above reproach, but her ties to the UK’s First Couple muddies the waters of her supposedly impartial counsel. Carrie Symonds, as we know, has managed to bend Boris’s ear when it comes to the green agenda. On both sides of the Channel, these agendas are worthy, necessary, even. But when the personalities dwarf the principles themselves, you know something is not quite right. As for Blanchard, his ascent may rival Rastignac’s, but he has a long way to fall should the election not go Macron’s way next year.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.