Of the two dictators who began World War Two as allied partners in crime but ended it in combat to the death, there is no doubt who has received more attention from historians and in the popular imagination. So much so, indeed, that the conflict is often labeled ‘Hitler’s War’.

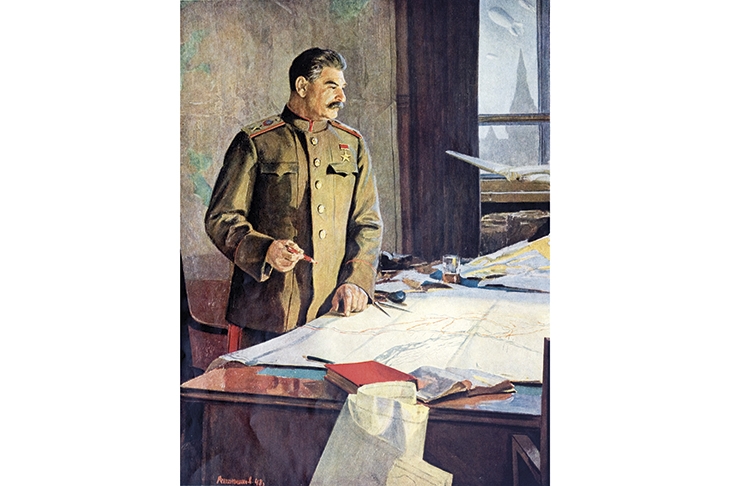

In this unashamedly revisionist account, the American academic historian Sean McMeekin asserts that we have been looking at the war through the wrong end of the telescope. The tyrant who, while not launching the conflict, took advantage of the circumstances that it presented at every turn, and certainly ended up by winning it, he says, was the man he constantly calls the Vozhd (the boss): Joseph Stalin.

McMeekin backs up his claim with a mountain of evidence culled from Russian, German and English-language sources. Stalin, he suggests, aided by communist agents such as Alger Hiss and Henry Dexter White in the US, and the Cambridge spies in Britain, who had penetrated the upper echelons of the Allied administrations, ran the war as the master manipulator that he was, pulling the strings of Washington and London like a well-practiced puppeteer. As a result, he bamboozled the western Allies into supplying him with the sinews of war. Vast quantities of tanks, trucks and warplanes, sorely needed on the western fronts, were shipped to the Soviet Union, along with war-winning technology including the secrets of the atomic bomb, helpfully delivered to Moscow by Stalin’s spies.

So desperate was the West for Soviet support that they let Stalin get away with mass murder. As McMeekin rightly underlines, there was no moral difference between the two totalitarian regimes. Stalin and Hitler invaded and occupied the same number of countries (seven) and while the Nazis had their concentration camps, Stalin had his Gulag. Even the ultimate horror of the Holocaust was rivaled by the Soviet Holodomor — the deliberately induced famine in the Ukraine that also killed millions.

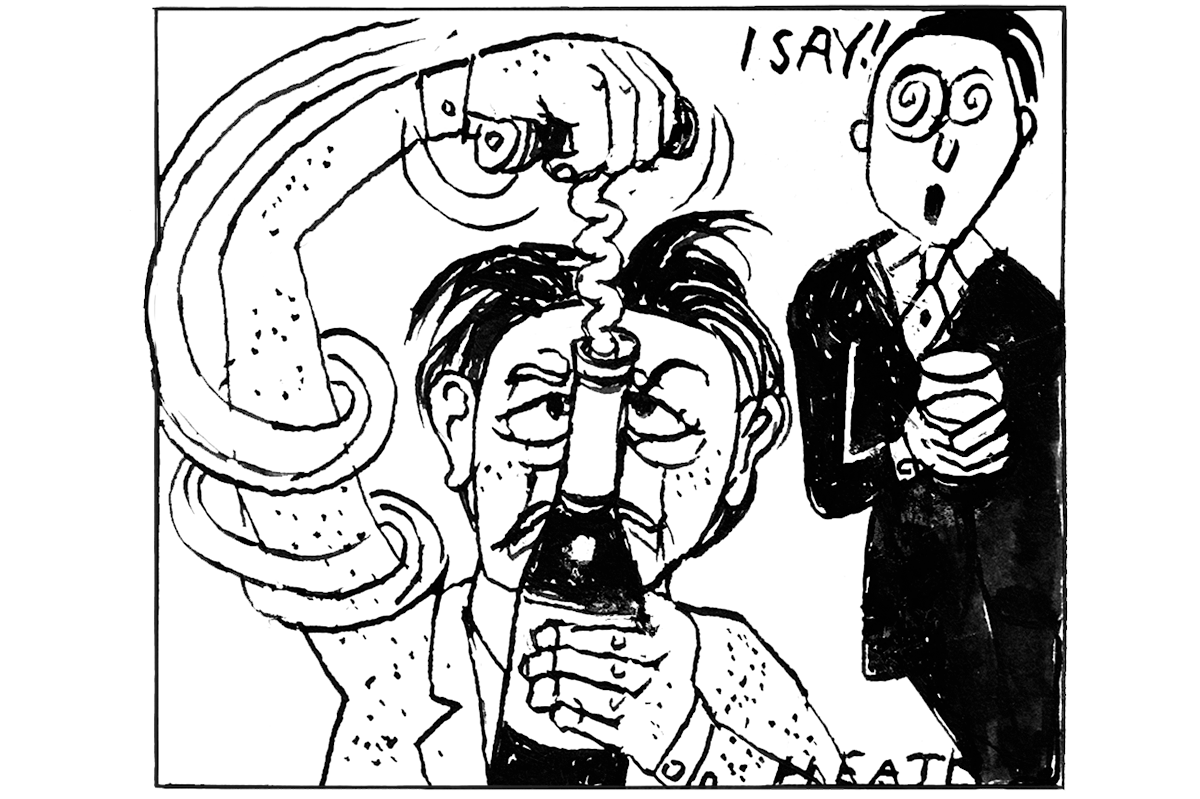

The West turned a blind eye to such Soviet crimes as the Katyn massacre of Poland’s elite, replacing a coldly realistic view of their future Cold War foe with the sentimental image of a cuddly ‘Uncle Joe’, a benign, pipe-smoking figure devoted to peace and progress. As a result, by the war’s end there was nothing that the West could do to stop Stalin from swallowing Poland — the country on whose behalf Britain had entered the war — along with the rest of Eastern Europe into an enslavement that lasted until 1989.

McMeekin’s portrayal of Stalin as a super strategist playing the long game extends from Europe to Asia, where he highlights Soviet intervention in Manchuria in the war between China and Japan. In considering the war from a global perspective and shifting the focus from a Eurocentric view, he provides a refreshing corrective that takes in areas of the war often overlooked by westerners. But when he abandons the role of the historian and turns from investigating what did happen to imagining what might have happened, his thesis looks less convincing.

He suggests that the West should have stood up to both Stalin and Hitler at an early stage in 1939-40 by backing Finland against Russia’s invasion of that country in the ‘winter war’. He blithely ignores the fact that the US did not join the war until it was attacked by Japan in December 1941, and the fiasco of the Anglo-French Norwegian campaign in 1940 does not give confidence that Allied intervention in another Scandinavian nation would have been any more successful.

His counter-factual scenarios enter the realms of absurdity when he suggests that Hitler’s fascist satellites Italy and Hungary might have joined the Allies in such an intervention, and/or that Britain should have become a de facto ally of Hitler by negotiating a peace deal with the Nazis in 1941 before they attacked Russia.

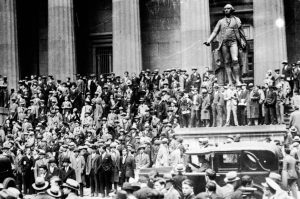

The truth surely is that the western Allies backed Stalin for reasons of realpolitik. Russia was doing the heavy lifting in the war from 1941 to 1944, losing many millions of lives in the process. Had Hitler succeeded in smashing the Soviet Union — as he nearly did — the outcome of the war would have been very different, involving a Nazi-run Europe and probable Japanese domination of Asia. This would have been an even worse result than what actually occurred, which McMeekin rightly regrets.

The fact that the war led to half a century of oppressive Soviet rule in eastern Europe and the loss of China to communism was a tragic by-product of the West’s weakness rather than the Machiavellian cunning and far-sightedness that McMeekin attributes to the all powerful Vozhd.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.