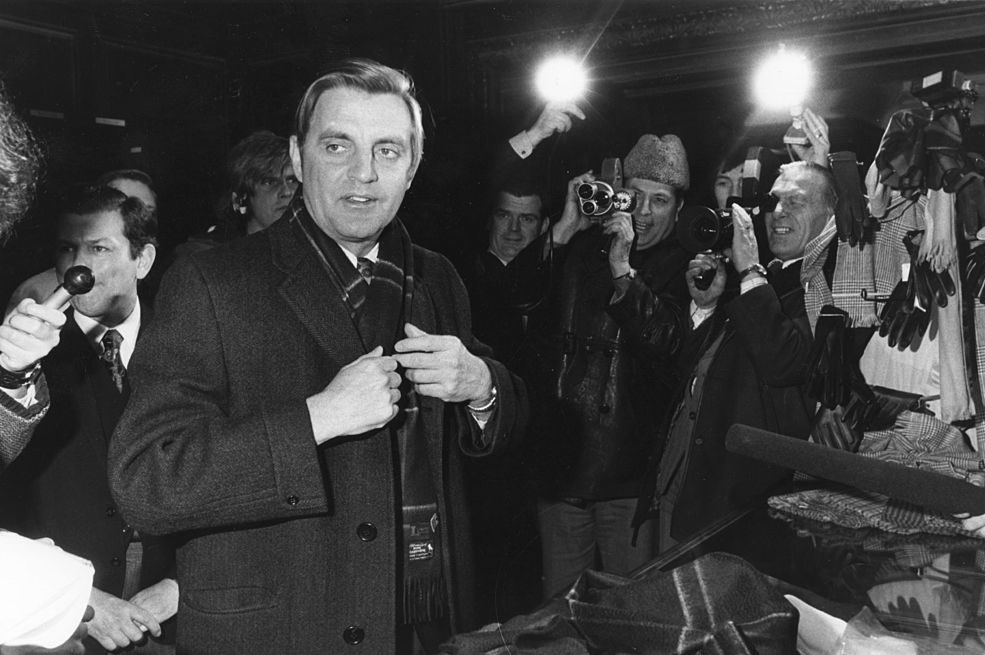

Walter Mondale, who has died aged 93, is destined to be a trivia question: ‘which die-hard liberal did Reagan beat by a landslide in 1984?’ That’s unfair. He had brains, looks and a presidential temperament. He was just out of time.

Here’s my Mondale anecdote. I interviewed him for my PhD in 2005 at his office in Minneapolis. He offered me a coffee; I said yes, and was then stunned when he got up from his desk and made it himself. This is unheard of in US politics. ‘I can’t wait to tell the folks back home that a vice president of the United States made me coffee,’ I said. Mondale sighed. ‘Nowadays,’ he replied, ‘it’s nice just to have something to do.’

He had a great sense of humor; the problem was it was deadpan and it paled in comparison to Reagan’s. Reagan famously sealed the ’84 election with a quip during the second debate that he wouldn’t use Mondale’s relative youth and inexperience against him. Some even wondered if Mondale’s greatest weakness was that he was Norwegian-by-descent, that he came across as ponderous, even sad compared to Mr Morning in America.

But that’s to remember history backwards. Mondale had much more going for him than that. Appointed to the Senate from Minnesota in 1964, and easily elected in 1966, he was on the center-left of the party, not the far-left. In 1976, Jimmy Carter tapped him to be his VP in an effort to balance a southern moderate with a northern liberal. It was a winning combination.

In office, Mondale created the modern vice-presidency: not just a spokesman for the administration, he was a genuine partner, although he eventually learnt the limits of his advice. In 1979, Carter — drowning in inflation and rising unemployment — declared that America suffered from a ‘crisis of confidence’, that its problems were moral rather than just political. What we now know is that Mondale was so disgusted with this idea that he threatened to resign. Such was his anger that friends thought he was going to have a heart attack. Mondale believed that, first, leaders should never blame the electorate for their cock-ups and, second, government, though flawed, was ultimately the solution to policy challenges — not thoughts and prayers. Mondale was right; Carter was wrong. ‘Crisis of confidence’, aka “malaise” helped defeat Carter in 1980.

Mondale could and should have run for the presidency in 1984 from the center. The problem was that his primary duty was to reunite a shattered party, and facing rebellions on the left (Jesse Jackson) and right (Gary Hart), he tried to revive the New Deal coalition politics that were fast going out of style.

Mondale could be very funny too. He put Hart in his place by quoting a fast-food ad to highlight his lack of substance: ‘Where’s the beef?’ he asked during a debate. And let the record show that until late 1983, early 1984, Mondale was actually tying Reagan in some polls. Reagan had done poorly in the 1982 midterms thanks to a post-Carter recession.

But Mondale ran as Mondale. He decided to be honest with the American people about the deficit and pledged, in a reversal of all electoral logic, that he would raise taxes.

He also let it be known he was looking for a VP candidate who wasn’t white or male, and wound up picking Geraldine Ferraro because she was female and a Catholic. This smacked of identity politics — piecing together a coalition based on appearance rather than ideas — and back then this was very unpopular. Today it’s Democratic strategy.

Poor Ferraro had a good record in her own right as a prosecutor, but being selected this way made her look like an affirmative-action hire, and Mondale didn’t really know what to do with her during the election. He snatched some hope from his first debate with Reagan, which, believe it or not, he easily won: Reagan looked visibly ill, and that’s why he had to roll out that zippy one-liner at the second debate, putting Mondale back in his place.

Ultimately, Mondale couldn’t win ’84. The economy was bouncing back. Reagan had ‘liberated’ Grenada from a rabble of reds. And the Gipper seemed to wake up at the last minute, reminding voters of why they loved him. Plus, the kind of liberalism that Mondale, wittingly or not, had become associated with looked tired (the genius of Reagan was despite being much older than many of his opponents, he seemed younger, more in touch with the direction of affairs). At the next election, 1988, the Democrats chose a wonk over an ideologue — Mike Dukakis — and thereafter went with Bill Clinton, a more competent Carter. Mondale became a symbol of the failed aspirations of the 1960s.

His politics are not mine, but of all the failures of that time, I’d wager none had a character that was better suited to the office of president.