I am always irritated by film versions of classic novels, especially when I’ve recently read them. I needn’t have worried about Death on the Nile. Kenneth Branagh’s Agatha Christie adaptation, already subject to no fewer than six delays, has been pushed back yet again to the first quarter of 2022. By the time it comes out — if it does — I’ll have forgotten the original.

With that airless sense of ‘here we go again’, Nile’s delay has been caused because its leading man, Armie Hammer, has been accused of sexual assault, including rape, and sundry other unsavory forms of sexual conduct — allegations which he denies.

In an age in which far lesser alleged infractions than Hammer’s routinely destroy careers, the chances of my ever having to clash with Disney’s interpretation of Death on the Nile on the big screen are, in fact, extremely slim — insiders expect Disney to skip a cinema premiere altogether and quietly go straight to streaming on Hulu.

It’s not even possible, according to the latest reports, for the studio to simply cut Hammer out and reshoot the role as they did with Kevin Spacey in All the Money in the World in 2018 after Spacey was accused of sexual assault. Hammer is too big a part, and the film is done. Disney is waiting and watching the scandal unfold, but it’s hard to see how it can ever go away. Once accused, the stench around a disgraced actor is permanent.

It will be some time before a legal and police verdict are delivered on Hammer. But the outcome of those inquiries doesn’t matter and we all know it. Disney knows it, and so does everyone else who has ever worked with Hammer, or ever will. Since rumors about Hammer first appeared on Twitter in February, long before the accusations reached their present gravity, he was fired from Shotgun Wedding, a romcom with Jennifer Lopez; The Offer, a Paramount film about the making of The Godfather and Billion Dollar Spy, a Cold War thriller opposite Mads Mikkelsen. His involvement in a bevvy of future commitments, including a Broadway play The Minutes, the sports comedy Next Goal Wins and a potential sequel to smash hit Call Me By Your Name, now looks unlikely.

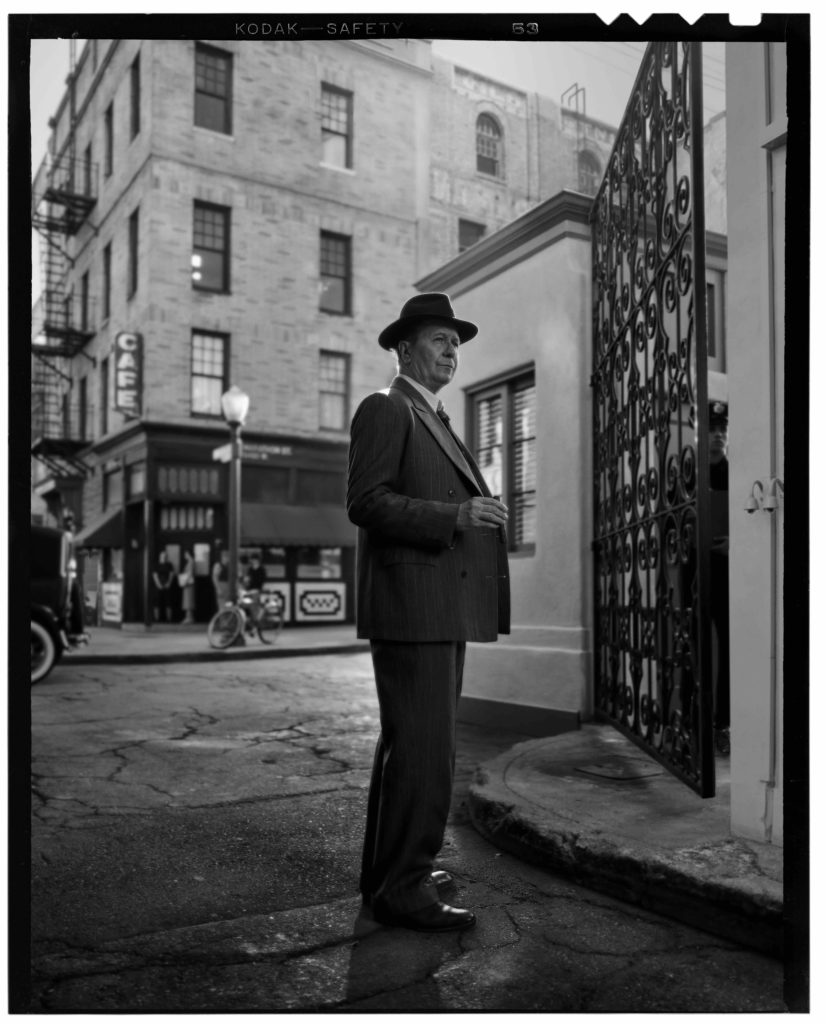

Since #MeToo, the process by which alleged crimes are converted into instant cultural, social and professional death has attained warp speed. The sole exception to this logic, however, is Jews: it appears that you can say or do almost anything against Jews and not only avoid cancellation, but be cast as a Jew in a starring role. Take Gary Oldman, who in 2014 let loose an anti-Semitic rant defending Mel Gibson (another non-canceled famous anti-Semite). Instead of being chucked out never to return, after a mealy-mouthed apology in 2014 he is currently starring in Mank, about Herman Mankiewicz, the Jewish producer of Citizen Kane.

In the last few years, even the renegade have stopped arguing for a divide between art and the biography of the artist. Suggesting that a Hammer, or a Woody Allen or a Kevin Spacey or a Johnny Depp are still the best men for the job would be almost as great a taboo now as appearing to shrug off rape itself.

That Hollywood should have devoted itself to being such a punctilious, committed guardian of the moral purity of its stars is ironic, and occludes a long history. On paper, of course, Hollywood has long been interested in the personal morality of its stars, introducing Morals Clauses in the 1920s. The Morals Clause gave studios the right to terminate actors’ contracts if their behavior threatened the perception of the enterprise or the actor’s ability to do their job, but was often used to sack stars whose popularity was on the wane. Once someone was terminated by a Morals Clause, word could get around, and their career might never recover, just like today.

But unlike today, major stars could get away with a lot if they were good enough at what they did. Frank Sinatra was pursued by allegations of Mob connections, including the strong suggestion that he mixed with Mafia murderers and may have had people rubbed out. There were also multiple stories of what would now be seen as inappropriate behavior to women.

Actress Tippi Hedren, who starred in The Birds, alleged in 2016 that Alfred Hitchcock sexually harassed her during the shooting of the film. Yet Hitchcock was not canceled: indeed, many of his contemporaries rallied to his defense. Fatty Arbuckle, however, is one that went too far: when the silent screen star allegedly raped and caused the death of a young woman a century ago, he was tried several times for manslaughter and acquitted, but scarcely worked again, and could only work as a director under a pseudonym.

Generally, the Morals Clause was used strategically rather than in a totalitarian way, and in the interests of revenue more often than actual moral outrage. Today, the financial advantage of cutting actors on the grounds of moral contamination is less clear. Death on the Nile has been made at great expense. But whether audiences are keen to see it or not, studios know that nothing is more widely off-brand than being associated with someone who is perceived to have broken rank with the moral code of the day (again, a code that does not seem to include anti-Semitism).

But do ordinary punters really decline to see a movie because the leading man has a tawdry private life? A few years ago, the answer would, I think, have been no. But today, the creep of the terror at being associated with morally toxic goods is enough to make a film studio sacrifice millions. Friends now dump friends over ‘offensive’ words; people routinely choose ideology over their own pleasure and friendships. It figures that many will switch off on the grounds of moral disgust at an actor; a 23-year-old I met recently said that he (he!) wouldn’t watch a Hammer film now.

Hollywood is on high alert when it comes to this kind of outrage, perhaps because of its ability to spread like wildfire online. Such is the fear of moral contamination that self censorship is even applied retrospectively to films like Death on the Nile that were made before the allegations against its star came to light. The industry fears young, taste-making audiences who can turn their backs not just on single films but entire studios at the first sign of a scandal. Death on the Nile won’t be the last casualty; it’s only a matter of time before a new culprit emerges.

This article was originally published on Spectator Life.