Two millennia ago, in the outer reaches of the empire, the Romans performed a routine execution of a Galilean rebel. Tortured and publicly humiliated in front of family and friends, Jesus of Nazareth was slowly asphyxiated over six hours.

The Crucifixion is the centerpiece of Christianity. But artists have long adapted the devotional image of the Cross for their own purposes. As far back as the early 5th century, woodcarvers working on a door for the Basilica of Santa Sabina in Rome crafted a Christ whose palms are impaled with nails, but who is not hung on a cross. A devotional statue in Panama dating from the 17th century made Christ not Middle Eastern, but black African. James Tissot (c. 1890) and Salvador Dali (in 1951) radically altered our sense of the scene by treating it from the divine perspective.

Yet from the mid-20th century onwards the Crucifixion became a vehicle for artists of great faith and none to get visceral and political. In contrast to the classic depictions from the Spanish Golden Age by Alonso Cano (c. 1635) and Diego Velazquez (c. 1632), these artists reclaimed the Crucifixion for what it was — a repulsive spectacle and a raw human image.

One of the most outrageous reworkings is by a Catholic — the American artist Andres Serrano, whose ‘Immersion, Piss Christ’ (1987) is a photograph of a crucifix dunked in a jar of the artist’s concentrated urine. Thinking ‘Piss Christ’ sacrilegious, believers in the United States protested — and completely missed the point. After centuries of sanitized portrayals of a galling public execution, it took Serrano to resurrect the ignominy of Golgotha.

Serrano’s piece places us, the viewers, in the position of the witnesses — Joseph of Arimathea, the Marys and the rest who watched as nails were beaten into their friend’s flesh, heard the taunts of the thief beside him, and had no idea this was not the end. ‘Piss Christ’ is a religious piece of rare power. It challenges us to see beyond the clichés of the Crucifixion and reimbues Christ’s death with its original potency.

Serrano wasn’t the first to produce a radical version of the Crucifixion. Responding to the horrors of the 20th century, artists returned to the Cross to frame their contemporary protests.

The Belarusian Jew Marc Chagall, who frequently depicted Old Testament scenes, was compelled to liken the persecution of European Jews in the 1930s to the torture of a Galilean one in the AD 30s. By substituting Christ’s crown of thorns for a white headcloth, and his loin-garment for a prayer shawl, Chagall’s ‘White Crucifixion’ (1938) emphasizes Jesus’s Jewishness. The figures that surround Jesus are not his followers, but Jews fleeing pogroms.

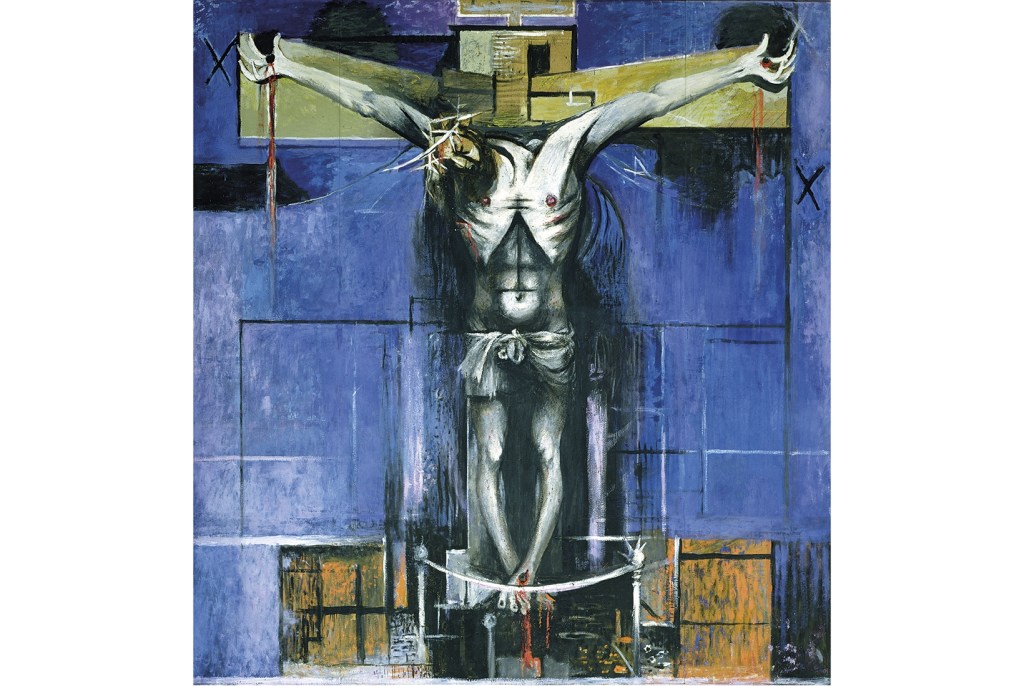

The Crucifixion was also recast in the light of Jewish suffering by Graham Sutherland, a Catholic convert. His ‘Crucifixion’ (1946), commissioned for St Matthew’s church in Northampton, draws on photographs of the survivors of Buchenwald, Belsen and Auschwitz. It’s harrowing, showing Christ’s protruding ribs and disfigured shoulders.

Sutherland’s friend Francis Bacon, by contrast, repeatedly applied the motif in ways that seem to have little correlation with Christ’s death. In ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (1944), Francis Bacon removes any clear depiction of Christ at all. There are instead three monstrous figures framed in triptych. The painting suggests not redemption but the triumph of demons. For Bacon, as for many in 1944 when he painted it, Christ feels absent.

Bacon saw the Crucifixion not in theological terms but as a metaphor for humans’ capacity for cruelty. ‘As a non-believer,’ he explained, Christ’s execution ‘was just an act of Man’s behavior to another.’ Enticed by its rawness, Bacon used the theme voraciously. At a 2008 retrospective, Tate Britain devoted an entire room to his Crucifixions.

Bacon may have changed what Crucifixion art could be, but even when he upended the tone and content, he remained influenced by orthodox portrayals. His simplest, from 1933, shows a ghoulish, skeletal, animalistic figure with a translucent body, reminiscent of those by Cano, Velazquez and Goya.

Slaughterhouses, Bacon believed, belonged to the Crucifixion. In Bacon’s ‘Three Studies for a Crucifixion’ (1962) Golgotha becomes an abattoir, and his Christ an animal carcass. The allusion is emphasized by the undulating shape of the cadaver, which recalls the twisted form and skeletal fingers of Cimabue’s Crucifix (c. 1265) in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence.

Fernando Botero also rages against a violent world, but approaches the Golgotha scene with dry humor. Turning away from the classic, beautiful depictions of Christ from the Spanish Golden Age, the Colombian applies his customary unflattering eye to ‘The Crucifixion’ (2011). Botero’s Christ is portly and undignified. Christ’s chubbiness and Botero’s smooth brushwork contrast dramatically with his crucifixion.

Like Gauguin, whose ‘Yellow Christ’ is crucified not in Jerusalem but the French countryside, Botero relocates Golgotha to Central Park. Instead of Jerusalem’s ancient walls, Manhattan skyscrapers fill the background. The painting is part of a series that compares the Way of the Cross to Colombia’s violence, of which the US has long been a root cause. Christ’s body is depicted in rust-green like the Statue of Liberty. Past the giant cross and green Christ, park-goers blithely push prams.

Twentieth-century artists may have provoked the ire of believers with their interpretations but they rescued an image made mundane by centuries of sanitization, recapturing the original feeling of witnessing Christ’s execution.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.