I’m thrilled to tell you that my latest novel has been optioned by Netflix. Grand Prix Grandpa is the inspirational story of an ordinary journalist in his mid-fifties who reboots his life by becoming a world motor-racing champion. It’s tough at first driving round racetracks at 230 mph when your eyesight is going and your reflexes aren’t what they were. But with a little practice and a lot of determination, Grand Prix Grandpa — whose name is James, by the way — becomes F1 champion, then triumphs heroically over the resulting problems: semi-naked women hurling themselves at him; having so much money he doesn’t know what to do with it; the loneliness of tax exile in Monaco, etc.

No, not really. I didn’t write it, it wouldn’t get published and Netflix definitely wouldn’t option it, not least because the whole premise is quite ludicrously implausible. But no more ludicrously implausible than the plot that Netflix has turned into a successful TV series, Walter Tevis’s The Queen’s Gambit, about the adventures of Beth Harmon, the most brilliant chess player in the whole world who just happens to be female.

Tevis sounds an interesting character. His other works include The Man Who Fell to Earth (adapted into an unsettling Nicholas Roeg movie with David Bowie as the alien) and two pool novels, The Hustler and The Color of Money, both of which became Paul Newman movies. He taught English at Ohio University and died young aged 56, tragically depriving the world of a potential future late-blooming Nascar champion.

His female world chess champion premise isn’t more impossible than my middle- aged racing driving fantasy scenario, but it is unlikely to the point of intelligence-insulting. I’m sure there are many, many brilliant female chess players, but never once has one become a world champion. The only woman ever to have won a game against a reigning world number one is Hungary’s Judit Polgár. When she retired in 2015, she was ranked eighth in the world: impressive, but it still means that there were seven players better than her, all men.

I mention this only because hardly anyone else will. Woke reviewers will love The Queen’s Gambit because of its heartwarming female empowerment, whereas if they had any critical faculties they should love it — as I do very much — despite its hackneyed and tiresome ‘You go, girl!’ undercurrents. It amazes me that I liked it, but I really, really did. The performances, especially Anya Taylor-Joy’s utterly mesmerizing Beth Harmon — are so beguiling and real that they render the fantastical plotline totally believable. ‘Yes, it’s a whipped cream, spun-sugar confection,’ you murmur to yourself as Beth spends five episodes consuming enough booze and prescription tranquilizers to floor an elephant and still remains fresh, beautiful and capable. ‘But, damn, it tastes so good I want some more!’

One quality largely absent from the script is jeopardy. Beth rises effortlessly from ‘little girl at the orphanage taught to play by grouchy caretaker in the school basement’ to global superstar. After her first few trial games, she barely loses. This ought to be a major flaw. The greatest Bildungsroman-style films you ever saw — Barry Lyndon, say — all put their hero or heroine through tortuous ups and downs, to keep you on the edge of your seat. But The Queen’s Gambit barely bothers at all.

For example (at the risk of spoiling the plot), the grouchy janitor (Bill Camp) doesn’t turn out to be a secret pedophile; nor does the Dad who adopts Beth, though we may briefly suspect it. And the moment when her lovable adoptive Mom Alma (Marielle Heller) coughs ominously after one too many Martinis is not a signal (as it invariably is in movie-world) of the imminent onset of terminal lung cancer. Almost every time you’re expecting a dramatic setback it doesn’t actually transpire.

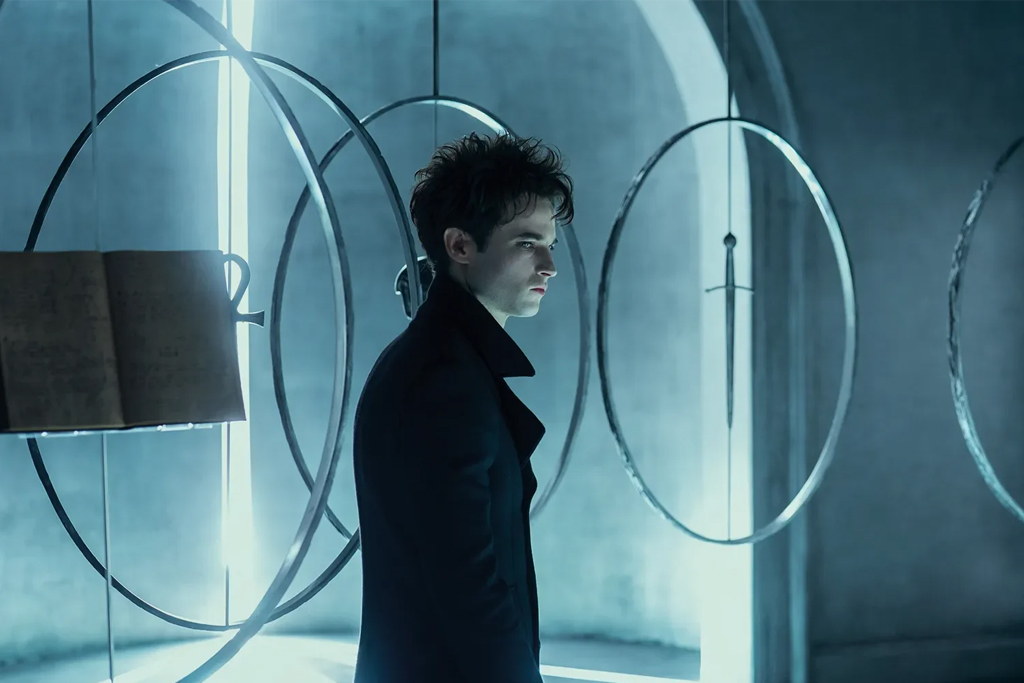

This breaks all the rules. Yet the show gets away with it. Partly this is down to the superb ensemble acting and all the variously quirky, likable, interesting characters we meet on the way, such as baby-faced chess genius Benny (Thomas Brodie-Sangster) in his leather coat and broad-brimmed gangster hat. Partly it’s down to the exquisite artistry of the design, look and feel of a movie made by a director-writer (Scott Frank) at the absolute top of his game. Even the chess matches — and there an awful lot of them — are endlessly varied, seductive, involving.

I’d almost call it high-end retro pornography. It’s set mainly in the mid-to-late Sixties, and every detail — the immaculately chosen soundtrack, the gorgeous, bordering-on-Audrey-Hepburn outfits Beth wears, the interiors and exteriors (from small-town Kentucky drugstore to student campuses to ritzy hotels in Vegas and Mexico City and Paris) — is observed with such loving fidelity it feels as if you’re actually there. Gabriele Binder (costume design), Daniel Parker (hair and makeup), and Uli Hanisch (the production designer who also did those glorious art deco sets on Babylon Berlin) deserve to clean up at any awards.

I wanted to hate this girlie nonsense, really I did. But it’s a dreamily, addictively adorable borderline masterpiece and more than worth seven hours of your life.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2021 US edition.