Since Emmanuel Macron became president last year, he has unashamedly courted the world’s presidents, prime ministers, sheiks and chancellors. Much like Trump, his message has been clear: France is not only back, but it is great again.

Trump and Macron will have the chance to discuss their strategies later this month when the American president hosts his 40-year-old French counterpart on the first official state visit by a foreign leader since his election. They first bonded in July when Trump was invited to Paris to revel in the pomp and ceremony of Bastille Day, against the grand historical backdrop of the Palace of Versailles, with all of its symbolism of French victory.

But while Trump’s approach has involved talk of fire and fury, Macron has adopted a gentler, more refined tactic. It seems to be working: according to the Soft Power 30 index, compiled by the University of Southern California Center on Public Diplomacy, France has now overtaken the USA to become the world’s greatest soft power, and that was before Macron’s recent announcement that he will spend €1.5 billion in the next five years as part of a new national strategy for artificial intelligence to rival that of China and the States. Not that Macron is just soft power. As he’s shown this week in his hawkish approach to Syria – a crisis that has conveniently erupted at a time when he is beset domestically by strikes and protest – he is willing to be as belligerent as Trump on the world stage.

But Macron’s principal political weapon has been French culture. In November, Macron flew to the Gulf to open Louvre Abu Dhabi. The museum features work pulled together from France’s national museums and auction house. It includes early 17th-century Portuguese art, ancient Egyptian figurines and 15th-century Ottoman helmets, as well as work by Rodin, Giacometti and Van Gogh. Tristram Hunt, the former MP and current director of the V&A, described it as a ‘remarkable extension of French cultural prowess’.

On a visit to China in January, Macron arrived with a gift for Xi Jinping, an eight-year-old gelding from France’s presidential cavalry corps, a supposed ‘symbol of French excellence’. Last month it was India’s turn to be schmoozed. After greeting Prime Minister Narendra Modi with a bear hug when he arrived in New Delhi, Macron described India as a strategic partner of France in South Asia and added that he ‘wants to be yours in Europe’. He even found time to butter up Bollywood, saying that he wanted to see more films made in France (with the promise of tax credits) in order to encourage Indian tourism. And unlike Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau, Macron managed to avoid being ridiculed by his Indian hosts for wearing an absurd range of traditional outfits.

The film industry is also at the heart of Macron’s France’s agreement with Saudi Arabia, details of which were unveiled this week in Paris during a visit by Mohammed bin Salman, who, of course, was hosted by Macron in the Louvre. Next month the Kingdom will officially participate for the first time in the Cannes Film Festival, and cinema forms an important of its $64 billion project to develop the entertainment industry in the coming years. France will be at the forefront of the project, helping the Saudis set up a national orchestra and opera. “I can’t think of a better moment for the cooperation and construction of a cultural relationship with France, the capital of arts and culture,” said Awwad al-Awwad, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Culture and Information Culture.

The other cultural weapon being deployed in his soft power offensive is a linguistic one. In March, Macron announced his intention to have French ‘become the language which creates tomorrow’s world’, with children around the world reading Hugo and Dumas rather than Shakespeare and Dickens. Macron has even tried to lure London bankers and their families across the Channel with the promise of French lessons before they leave the UK.

Who does the French president hope suffers most from this cultural charm offensive? Britain, of course. Macron sees us as being paralysed by the bickering over Brexit and burdened with a weak and foolish political class. With Germany also floundering, Macron believes France has an opportunity to become the dominant force in Europe. Diplomacy, history, culture and language: it’s a war on four fronts and at the moment Britain is being soundly thrashed. So it’s time to strike back, more so than ever as Macron seems intent on replacing Britain as America’s go-to friend in Europe. If France wants a culture war, let’s give them one.

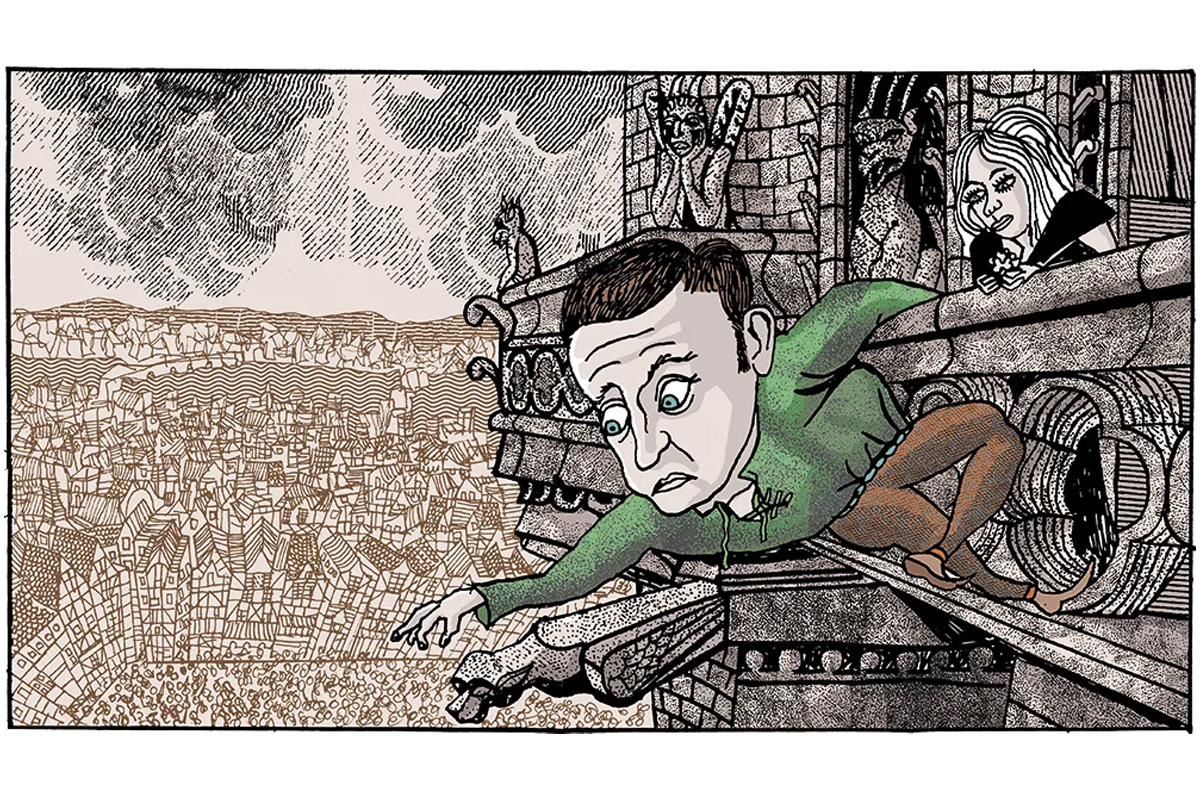

But the truth is, Britain has lost confidence in its own culture and history. We’ve lost our edge, turned ‘soft’, as the Stage magazine put it last year in regretting the refusal of the British theatre to address ‘the dominant narratives of our time’. The last cultural phenomenon to come from these shores, ‘Cool Britannia’, may have been a touch manufactured but it did at least feature in-your-face artists such as Oasis, Tracey Emin and Irvine Welsh. The zeitgeist today, rigorously enforced by the purveyors of identity politics, is conformity not controversy. There’s nothing cool about that. We can’t even claim that humour is still at the core of our culture given that every risqué joke risks offending someone or other. The French used to have an expression for our off-the-wall antics – ‘So British’ – but the phrase has rather gone out of fashion. A bit like Britain itself.

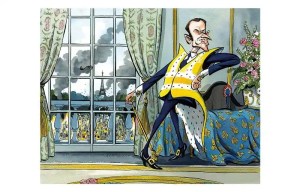

So to stand any chance of playing a part in Macron’s culture war, Britain will need to regain its cultural confidence – and make peace with its past. Macron doesn’t suffer from childish self-loathing. The one time someone tried to take him to task on the subject of post-colonial guilt was during a walkabout in Algeria in December. Forget about the past, he brusquely told his young inquisitor, and look to the future. That’s what he is doing, albeit by exploiting France’s grandiose past to sell a vision of the country that appeals to the leaders of China, India, America and the Gulf States; a country of Sun Kings and Chateaux, of Balzac and Boney. And how does Britain brand itself these days? When Theresa May visited China three weeks after Macron her gift for Xi Jinping was a Blue Planet boxset plus a message from David Attenborough asking China to help cut plastic pollution.

Macron is the antithesis of May in other ways. After the Manchester suicide bombing last May, the PM sought to rally the country with a watery speech declaring that “the liberal, pluralistic values of Britain” would prevail over an ideology she chose not to name. Macron, in contrast, gave a stirring address to the nation after last month’s terror attack in Trèbes, declaring that the Islamists would be defeated if France displayed the same courage and resolve as Joan of Arc, the Resistance fighter Jean Moulin, the infantrymen of Verdun and the cavalrymen of the Hundred Years War. For Macron, it’s possible to be patriotic and pluralistic.