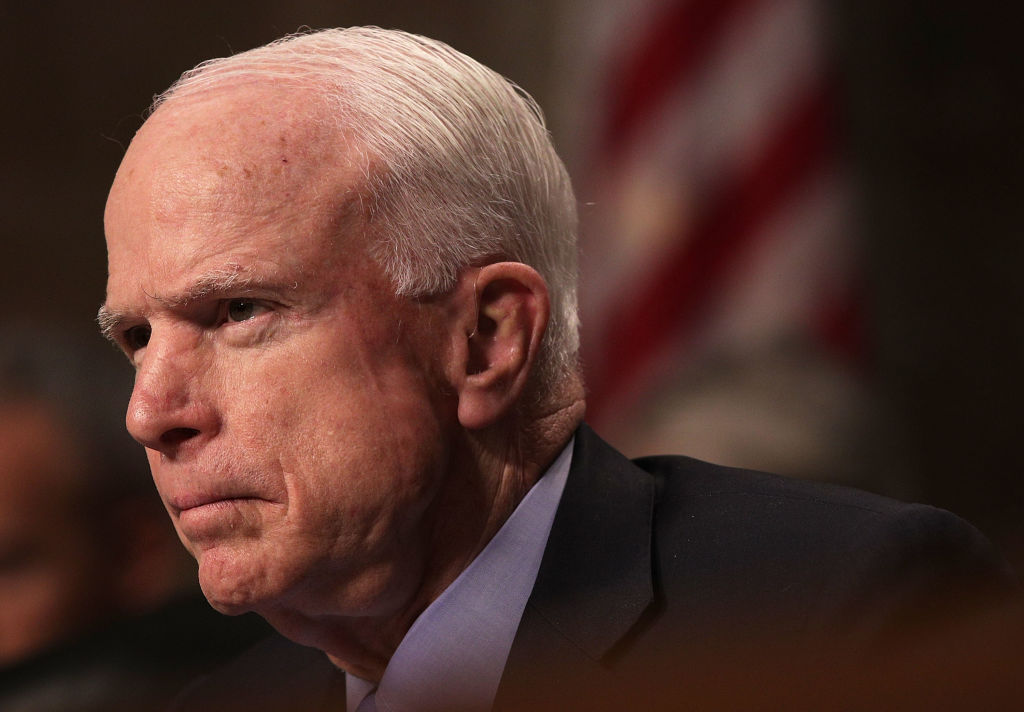

Has enough time passed since his passing — the fullness of a week! — that we may speak frankly of the political career of Senator John McCain

Nah. An honest assessment of the most rabid senatorial warmonger of the last half-century must await an American Spring. His worshipful acolyte Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina Republican, matches him bellicosity for bellicosity in the warmonger department, but an epicene epigone like Graham doesn’t count. McCain was the real thing.

So if we must now praise famous men, let us acknowledge John McCain’s witness against torture and his talent for exposing egregious pork-barrel projects, as well as his physical courage. As Dan McCarthy wrote on this site, he was an actual human being — no mean distinction in a body whose eminences include Marco Rubio and Dick Durbin.

But…

McCain also provided a museum-quality exhibition of the perils of placelessness.

Born in the Panama Canal Zone, and thus a child of US imperialism, he attended twenty schools in his deracinated boyhood. ‘The place I lived the longest in my life was Hanoi,’ he said, referring to his years as a prisoner of war.

The literature on the pathology of the military brat is extensive and doleful. ‘Mobility is associated with psychiatric casualty rates among both adults and children,’ according to researchers from the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Hypermobile children are prone to feelings of loss, depression, helplessness, anger. Everything is ephemeral; nothing lasts. Relationships are temporary. So is community. The ability to put down roots as an adult is severely compromised.

As the novelist Pat Conroy described his military brathood: ‘My job was to be a stranger, to know no one’s name on the first day of school, to be ignorant of all history and flow and that familial sense of relationship and proportion that makes a town safe for a child…Home is a foreign word in my vocabulary and always will be.’

This is profoundly sad. But the political consequences of such homelessness are ominous. Politicians without firm attachments to places will transfer their loyalties to abstractions and causes wholly unrelated to local lives, like ‘making the world safe for democracy’. The rooted, by contrast, will ask the great unasked question in American foreign policy: What does this war mean for my block, my neighbourhood, my town?

After marrying a rich girl — the path to success often hiked by ambitious men — McCain launched his political career in her home state of Arizona. He parried the charge of carpetbagging with irrefragable truculence:

‘Listen, pal. I spent 22 years in the Navy. My father was in the Navy. My grandfather was in the Navy. We in the military service tend to move a lot. We have to live in all parts of the country, all parts of the world. I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the First District of Arizona, but I was doing other things.’

That shut up his stick-in-the-mud interlocutor. Residence in the Hanoi Hilton is an unbeatable trump card. But the defiant assertion of rootlessness would be a major theme of McCain’s politics.

No wonder he expressed a willingness to keep American troops in Iraq ‘for a hundred years’. After all, one place is pretty much the same as the next. Homebodies who don’t want our young people in uniform dispatched to the furthest corners of the globe are just a bunch of pussies.

McCain’s infamous ejaculation that ‘We are all Georgians’ was not a nod to Ray Charles or Gladys Knight, but rather an expression of a grandiose universalism. This erases all particularity and local loyalties, making a license for unending military intervention in the affairs of other peoples, other nations. It is a line that could only be uttered by a person who belongs to everywhere, which is to say nowhere.

Senator Pat Moynihan (D-NY) once mused on the Americanness, or lack thereof, of the children of US military personnel who were growing up on or near the several hundred foreign bases that pimple the planet. This is a verboten topic in our Support The Troops age, but it had been raised with great urgency at the dawn of the Cold War, when a doughty little old lady in tennis shoes warned a Senate committee against ‘the principle of scattering the most virile of our men over the face of the globe’.

Or as soul singer Freda Payne phrased the question during John McCain’s war, ‘What they doin’ over there?/When we need them over here?’

I don’t mean to be churlish. If McCain had been interred with even a modicum of modesty I’d keep my mouth shut. But I gag on the cloying (and media-enforced) public piety regarding the death of a politician who advocated and effectuated the deaths — the murders — of multitudes of strangers. Besides, these state funerals reek of totalitarianism. They ill fit the republic we once were.

I used to work for the aforementioned Moynihan in the Russell Senate Office Building (SOB). It was named for Richard Russell, the Georgia senator who largely kept his deep reservations about the wisdom of the Vietnam War to himself, foolishly heeding the democracy-stifling maxim that ‘politics stops at the water’s edge’. (Policies do not, as over one million dead Vietnamese might tell us.) Senator Chuck Schumer, New York City Democrat, has proposed to rename the Russell SOB for John McCain. It’s the kind of cheapjack, meretricious act for which Schumer is known and loathed.

I’d not give a tweet in hell for any of the three current Senate Office Building eponyms (Russell, Michigan Democrat Philip Hart, and Illinois Republican Everett Dirksen). But whatever sins the humdrum trio of Hart, Russell, and Dirksen committed pale beside the deathstorm unleashed by John McCain, the Man from Nowhere.

Bill Kauffman is the author of 11 books, among them Dispatches from the Muckdog Gazette (Henry Holt) and Ain’t My America (Metropolitan).