São Paulo

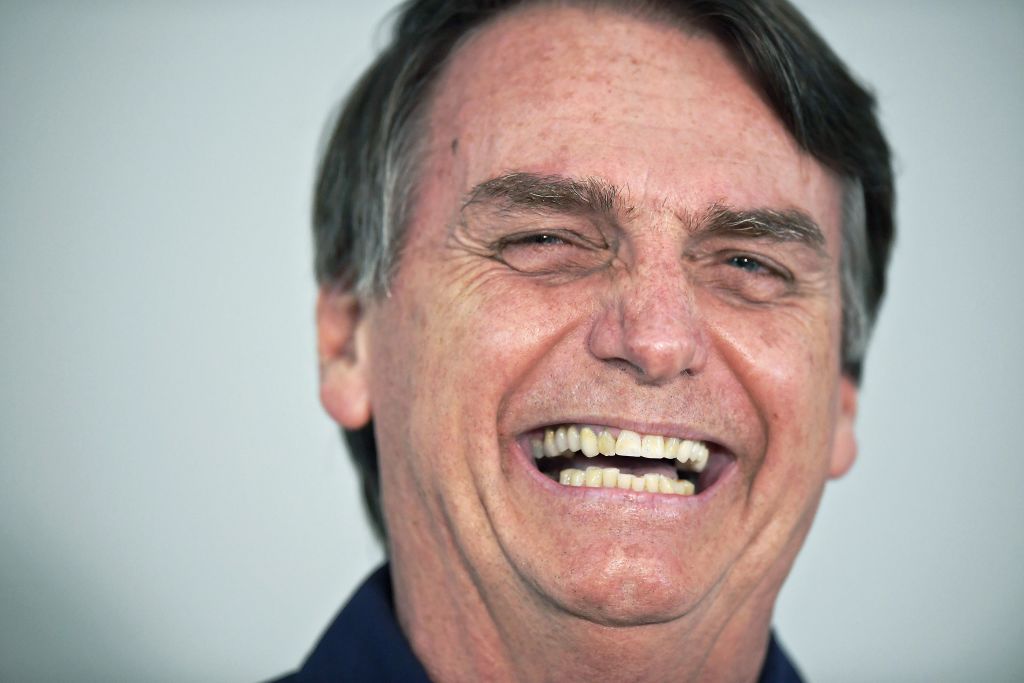

The most divisive election in recent Brazilian history wraps up tomorrow. Jair Bolsonaro, the right-wing populist, is the clear front-runner. Fernando Haddad of the left-wing Worker’s Party (PT) now lags far behind him in the polls.

Bolsonaro says what he thinks. He wants to relax gun laws. He favours the death penalty. He is a protectionist. He has the support of Brazilian evangelicals, nearly eight million Facebook followers, and only last month survived an attempt on his life. He was stabbed in the guts by a lunatic at a campaign rally in Minas Gerais, although plenty of conspiracy theorists believe the incident was in fact a stunt.

His popularity has soared since the attack and the exposure it has given him internationally is unquestionable. The image that now symbolises Bolsonaro’s rapid rise shows him in a yellow shirt, adopting a victorious pose on a man’s shoulders. It was taken seconds before he was attacked. As PR, the photograph is gold. There’s an uncanny resemblance to one the iconic image of Pele winning the 1970 World Cup, one of Brazil’s proudest moments.

Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right candidate in Brazil's presidential election, was stabbed at a campaign event on Thursday. https://t.co/Y6R8ibIh0T pic.twitter.com/ZDIQXyR8U3

— ABC News (@ABC) September 8, 2018

Western journalists might gasp in horror at ‘The Trump of Brazil’, another Steve Bannon-inspired populist winning power. But Brazilians don’t see it that way. Bolsanaro, relentlessly provocative and dismissive of political correctness, is widely regarded as the political saviour of a country that has been on the brink of economic and social collapse in recent years.

Bolsanaro trumps even Trump in the shock-value stakes. Back in 2011 in a TV interview about homosexuality, he said ‘It never crossed my mind that I would have gay children because they had a good education.’ He was fined for telling Congresswoman Maria do Rosario: ‘I wouldn’t rape you because you don’t deserve it.’ In 2016, he said during an interview with TV presenter Luciana Gimenez that he wouldn’t employ a woman ‘with the same salary as a man’ because women get pregnant. Quite a few of his supporters say they find these statements inappropriate. Still, they back him, because he offers them jobs and better life prospects.

The general levels of intrigue and clear ill-feeling surrounding this election are something that hasn’t been seen since 1964 when President João Belchior Marques Goulart was overthrown by the Brazilian Army, which established a military dictatorship until 1985.

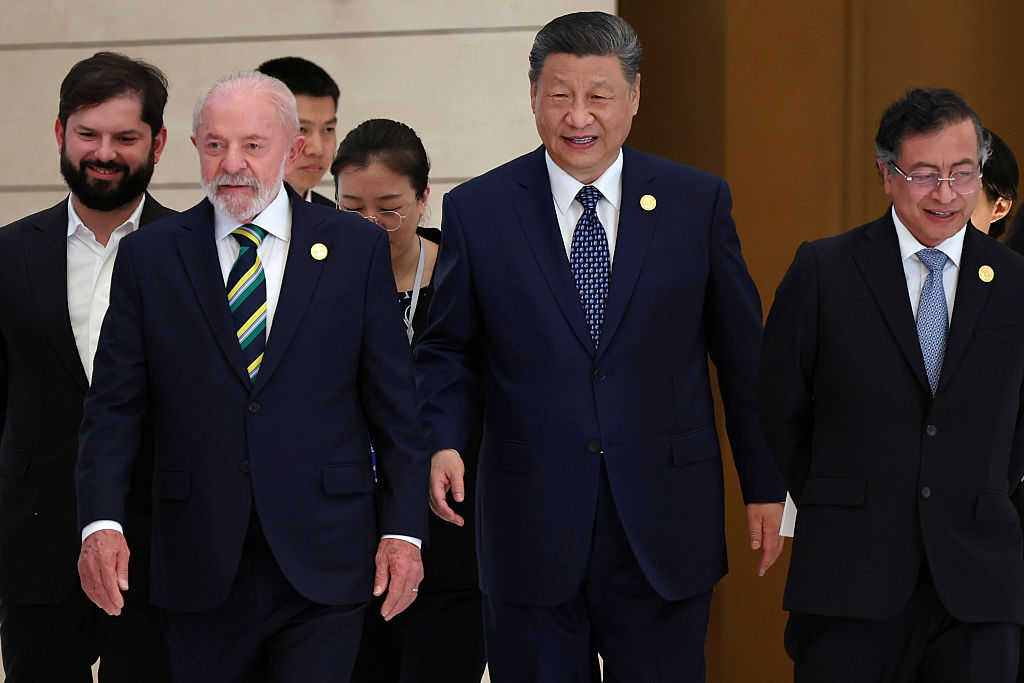

The Worker’s Party (PT) has been in power since 2002 when Lula da Silva — the man Obama called ‘the most popular politician on earth’ — won. In 2010, Dilma Rousseff replaced Lula after his second term came to an end. Yet Lula has continued to be the public face of the party. Until a couple of months ago, there was even talk of Lula standing to run in the 2018 election, despite the fact he is in prison for corruption on a massive scale.

The last 16 years in Brazil have been turbulent. What Brazilians refer to as the ‘good times’ peaked in 2010, as 40 million people joined the middle classes and the economy grew. It got more complicated after that as scandal after scandal have undermined the government, the economy and the country.

The Petrobras scandal of 2013 was the big one. It resulted in one of the 10 biggest companies in the world, valued at over $200 billion, losing 75 per cent of its value almost overnight. It soon emerged that $5.3 billion had been stolen by politicians in government kickbacks and bribes between 2004 and 2014. Brazilians can be quite apathetic about government malfeasance; but corruption on such a scale was unprecedented and shocking.

Things got worse. Brazil’s economy, for all its growth, relies on exports such as soy, iron and oil, which all crashed in 2012. The effect on the economy was catastrophic, the deficit soared as did inflation.

Foreign investment sank to a record low. The reputation of PT shattered. In October 2015, a Brazilian appeals court found President Dilma Rousseff unanimously guilty of cooking the country’s books. This led to her impeachment and a new President, Michael Temer. His popularity never got above 13 per cent and he was soon barred from running for elected office for eight years due to the violation of campaign finance laws.

It became clear that by 2016 the Brazilian people’s patience had snapped: more than three million took to streets to protest against government weakness and corruption.

Enter Jair Bolsonaro, a former military captain and parachutist. Outsiders see him as an authoritarian dictator in the making. His supporters tend to see him as ‘o cara tem colhões!’ The guy with balls!

Bolsonaro is proud of his military background. He promises to restore law and order. His opponents can call him a fascist for this as much as they want: but it’s a vote winner: nearly 64,000 people were murdered in Brazil last year, more than anywhere else in the world.

But corruption is engrained in Brazilian politics and the Bolsonaro campaign has been accused of fighting dirty, too. The last few days has seen one of Brazil’s biggest newspapers claim that Brazilian business leaders are illegally bankrolling a multimillion-dollar WhatsApp campaign aimed at boosting Bolsonaro’s popularity. Bolsonaro’s son Flavio found himself evicted from the social messaging platform as a result despite insisting he has nothing to do with the scandal. Bolsonaro and Haddad both accuse the other of spreading fake news.

Eduardo, one of Bolsonaro’s other sons also grabbed a few headlines by implying the military could very easily bring about an end to the Supreme Court; thus hinting at an imminent military coup. His father responded: ‘I have already admonished the kid, my son, he got it wrong’.

Like Trump, Bolsanaro takes a steamroller approach to environmental legislation. He stands for mining and a ‘more open’ approach to the Amazon. In this, naturally, he has the heavy backing of agribusiness and industrialists. He has even threatened to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement if Brazil doesn’t have full control over the Amazon. It’s no surprise that the stock index and exchange rate of the Brazilian real spiked after his first round win.

The anti-Bolsonaro campaign, #NotHim, is desperately pushing for a late swing back to Haddad and PT. But Bolsonaro has already survived being stabbed, and fights on. His victory now seems inevitable. To many Brazilians, he is the strongman they need.