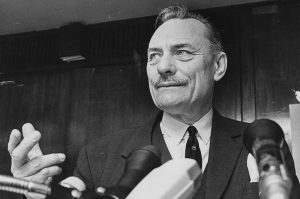

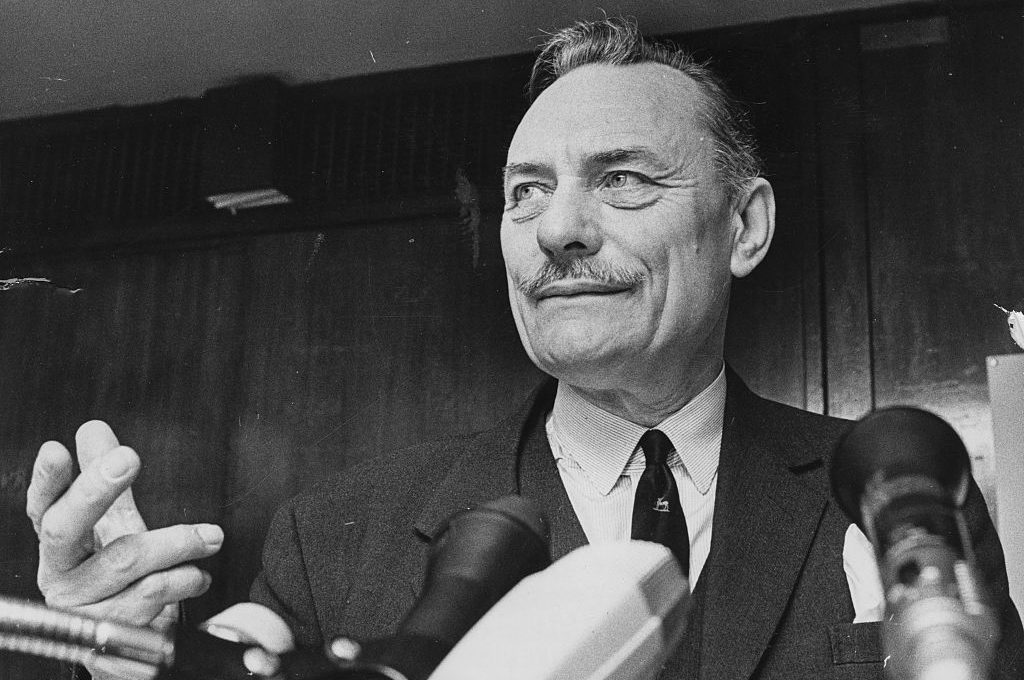

I meet Liam Fox at a tavern on St Martins Lane in central London. It’s spitting with rain outside the pub, covered in wood paneling floor-to-ceiling and eclectic memorabilia on every wall. We’re among just a handful of patrons, surrounded by empty tables spread out in accordance with social distancing guidelines. ‘People will say in my own constituency that they’re operating at about 40 percent capacity,’ Fox mentions when we’re talking about the prospects of a V-shaped recovery. He’s not optimistic: ‘It’s really hard to say…maybe is the answer’.

It’s a Sunday afternoon, but it’s clear the Rt Hon MP for North Somerset isn’t distinguishing between weekdays and weekends right now: between dealing with COVID concerns at home and campaigning to be the next director-general of the World Trade Organization — the global international body that sets the rules for trade between countries — Fox’s days aren’t measured by the working week, but rather by the series of deadlines for the nominees.

He has just made it into the second round of the contest, alongside Nigeria’s appointee, economist and former finance minister Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, and Kenya’s appointee, lawyer and diplomat Ms Amina C. Mohamed. WTO director-general Roberto Azevedo stepped down from the post earlier this month, leaving the organization temporarily leaderless during the largest economic crisis the 25-year-old trade body has faced. The disastrous impact of COVID-19, combined with trade wars brewing around the world, has piled further pressure onto the next director-general, but that hasn’t put Fox off. When I ask him why he thinks he’s the UK’s nominee, he’s abundantly clear: ‘I wanted it the most.’

In trying to single out what separates Fox from the other nominees, he puts emphasis on his status as an elected politician:

‘Whoever gets the job will have to have some fairly difficult conversations. I’ve already met and had dinner with President Xi, I’ve met President Trump several times when he was in Britain. I’ve met with Prime Minister Modi, Prime Minister Abe. These are people who have strong views. It’s not going to be easy for a bureaucrat to deliver difficult messages.’

Between his time as defense secretary under David Cameron and trade secretary for three years under Theresa May, there’s no question Fox has been in the room with some of Britain’s biggest political personalities — and most powerful ones too. When I ask him if his bid to lead the WTO would be an extension of his time as trade secretary, Fox confirms his commitment to free markets and free trade would prevail, but that his leadership would need to look different:

‘In terms of being a strong believer in an open and free trading system, seeing trade as an empowerment tool and believing that it’s much better to help countries trade their way out of poverty rather than have them trapped forever in an aid cycle, absolutely. But it’s different, of course, because the WTO is a member-driven organization, so you can’t be the boss, as it were.’

Before we get to his vision for the WTO, the effects of the COVID crisis on the global economy and the myriad of other issues facing free trade enthusiasts, there’s an outstanding question to be asked about his prospects: does Britain have a leg to stand on when it comes to promoting free trade, having just left the world’s biggest free trade bloc at the start of the year?

‘Yes,’ Fox says swiftly, ‘because the majority of our trade is not with the European Union.’ He insists that Brexit is not a make-or-break issue for the majority of the WTO’s 164 members looking to elect the next director:

‘Only on two occasions in 45 bilateral (conversations) has anyone raised the issue of Brexit. Yet every British journalist I have spoken to raises it. For most countries in the world, they regard Brexit as a bilateral issue between Britain and Europe, which they think will be sorted out. They’re much more concerned with the real horrors in the global trading system coming largely out of the COVID-19 picture. And that’s what they want to know about it.’

In the spirit of his point, I raise Brexit again — this time asking if he’d prefer to see a bespoke trade deal between the UK and EU secured, or if he wants the UK to trade with the EU on the terms of the organization he hopes to lead. The Brexiteer opts firmly for the former:

‘A treaty, without a doubt. If we can get a treaty agreement, so much the better. It provides much greater certainty because, even if we don’t get a deal, we will still be aiming for one at some point in the future. So the quicker we get it, the more predictability we give to business. I also think that there is an increased incentive to get one now, because of the disruption to the global economy. The one thing that’s really at a premium right now is confidence.’

Restoring confidence is a major theme for Fox, not just in the context of Brexit, but as a major factor in the global economy’s recovery from COVID-19, an issue that troubles him significantly more than tensions between the UK and the EU. Back to the prospects of a V-shaped recovery: ‘It’s really confidence that is the key element to that, particularly in the service-based economy.’

But Fox notes that we are not starting from an ideal place. ‘The trading system was broken before COVID and is under greater stress now,’ he laments. ‘Trade was already contracting in the final quarter of 2019. We’re in a worse position now than we were during the financial crisis.’

It’s not just the state of economies and their finances that troubles Fox, but attitude shifts as well: ‘We’ve become much more protectionist. Every two years on average, we’ve doubled the number of restrictive measures, making it much more difficult for a less wealthy country to trade themselves out of this problem. There are some uncomfortable conversations that will have to be had with the big countries about that. And I think that comes easier from a G7 country.’ And from an elected politician, he insists again.

But what happens if those tough conversations have to take place at home? Fox has built up a reputation for being one of the most pro-market members of parliament, and he’s not about to make exceptions for his colleagues — or Britain’s allies. When I bring up the UK government decisions to bail out of the steel industry and regional airline Flybe, he admits the line between national security and economic protectionism is a fine one:

‘You have to be very careful about what you exempt. The UK was very vocal about the US imposing tariffs on steel on the grounds of national security. Our view was that it isn’t national security, it’s national economic interests, and they’re not the same thing. Flybe was a very good example: there’s a limit to what you can do if something is uneconomic in the private sector; it is likely to be even more uneconomic in the public sector.’

He also notes increasing trade tensions inside the United States, as President Trump has brought what Fox describes as ‘a slightly more protectionist flavor,’ but he’s optimistic that the tide has not fully turned against free trade: ‘I know lots of politicians on both sides of the aisle who, in private, will say we actually require a more open, global trading system.’

How far does Fox’s vision for extending free trade reach? Multilateral agreements are his ‘gold standard’, including as many countries as possible in an open trading bloc. But he doesn’t throw pragmatism out with the bathwater:

‘There are those who say if there can’t be multilateral agreements, there should be nothing, because the WTO is a multilateral system. My view is that if you see plurilateral agreements as a stepping stone, that’s a totally different concept. Even tiny little baby steps to liberalization are worth having. If you can get big giant steps, that’s even better.’

For the UK, he hopes the next big step will be joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. ‘If you’ve got the UK joining (CPTPP) now, it would take it to roughly the same sort of share of global GDP as the EU has, minus Britain,’ he says gleefully. ‘And if you have the UK and the US rejoining, you’re at over 40 percent of global GDP.’

If the primary goal is to expand access to free trade, why not extend the invitation to China? His smile drops: ‘Well, it’s also about the nature of the beast.’

It becomes increasingly clear that for Fox, the value of trade is about more than the exchange of goods and services:

‘The current system, as set up in 1995, was there to purely get global trade moving. But it wasn’t without values. Built in was the concept that a more open system would bring development to people, bring freedom to people. Should we just be about commercial exchange? No. You should be about seeing that commercial exchange as delivering something much more.’

But if trade blocs like CPTPP are to take on the role of an economic Nato, does that mean that China, given its track record on human rights and law and order, would be left out of Fox’s plans for an increasingly connected world?

‘Many of us believed that if we increased trade with China, that might bring other change in its wake, which, of course, it has for many other countries around the world. And as yet has not happened with China. And there’s no sign of it will. But would I rather we had an exchange of goods with China than restrictions on trade? Yes, I would.’

If Fox finds himself in the director-general’s shoes this fall, the WTO could be facing a shake-up, not quite equivalent to what’s expected to happen in Whitehall, but perhaps not too far off. Making the organization ‘more efficient in terms of its set up’ is one of Fox’s top priorities, as he would ‘look to streamline and make things operate according to functionality.’ The biggest problem within the WTO, according to Fox, is that it has no dispute resolution mechanism, another priority on his list: ‘If you have a rules-based system that doesn’t have an ability to adjudicate disputes, you are in Alice in Wonderland territory.’

If Fox gets to implement change at the top of the organization, he will credit his win to one person in particular: Boris Johnson. ‘I’ve no doubt in my mind that the prime minister would have faced quite a lot of resistance putting up the UK nominee…and I think to his great credit, he simply took an executive decision and said we should go for it.’

Why the pushback, especially after every Tory candidate in the 2019 election signed a pledge to leave the European Union and embrace free trade around the world? Fox breaks down the leave camp into two groups, those that ‘wanted greater economic nationalism’ and those who thought the EU ‘wasn’t foreign enough’, wanting to ‘push the envelope on global liberalization faster.’

[special_offer]

‘Both groups can co-exist in the leave campaign,’ he says, but, ‘it’s much more difficult for them to co-exist in government because they have a mutually exclusive worldview.’ Johnson’s decision to appoint Fox as the UK’s nominee reconfirms for him what he always expected: ‘the Prime Minister and I are one of those easily definable groups.’

Throughout the campaigning process, Fox has been reminded when speaking to other countries to what extent Britain can take its commitment to law and order for granted: ‘We are in defense of the rules-based system. Those who are inside it, we support you. If you’re outside, we’ll be critical.’

That’s his message to the rest of the WTO member states. And his message to Britain: regain confidence. ‘There seems to have been a sort of collective loss of self-confidence in a lot of areas, particularly areas where we haven’t had competence for a while, like trade.’ Successful or not, now is the time WTO candidate Fox thinks the UK should be reclaiming its free trading credentials. ‘Surely if we believe in our own case as we come out of the European Union, and we believe that our vision of an open, competitive global environment is the best one, we have a duty to say it.’

This article was originally published onThe Spectator’s UK website.