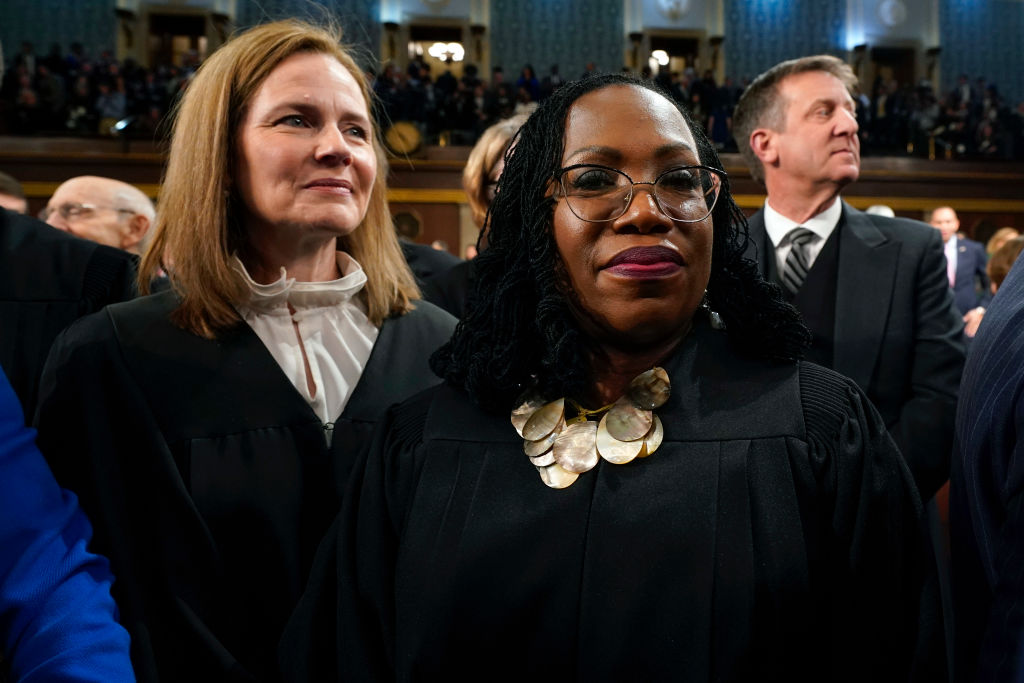

Americans hate the Supreme Court. You wouldn’t think so from a look at the polls, which usually show that the court is far more popular than the elected branches of government. But history tells a very different story. The conservative movement as it exists today was formed in large part as a reaction against the liberalism of the Supreme Court under chief justices Earl Warren and Warren Burger — both of whom were Republicans, as it happens. The progressive movement of the early 20th century and the populist movement of the late 19th century were also spurred to varying degrees by the character of the Supreme Court at the time, which was seen as conservative and elitist. Franklin D. Roosevelt was so frustrated by the striking down of various New Deal programs that he even wanted to ‘pack the court’ with additional more compliant justices in 1937. Today the cultural left dreams of doing likewise to offset President Trump’s appointment of a replacement for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.Amy Coney Barrett is supposed to tip the Supreme Court far to the right, cuing up the fall of Roe v. Wade and ushering in the theocracy of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. The first half of that is exactly what Barrett’s fans are hoping for. A byproduct of the hatred that the court generates among Americans deeply committed to left-wing or right-wing politics is that the justices who stand out from the consensus are turned into cult figures, either of worshipful devotion or of absolute demonization. This was the case with Antonin Scalia, who was for decades second only to Ronald Reagan himself in the conservative pantheon, and it was true for Justice Ginsburg as well, who was turned by progressives into a poptastic ‘Grrl Power’ icon — ‘Notorious RBG’ — and whose death has been the occasion for expressions of veneration as much as grief. Now Barrett is being celebrated by conservatives in a similarly personal way, with a focus on her large and happy family and on the odious attacks on faith, rather than on whatever her jurisprudence is supposed to be. The point, for conservatives and progressives alike, is that she will be strongly anti-abortion as an expression of her very essence and identity. She represents the undoing of the Warren Burger Court’s license for infanticide or, from the other perspective, the enslavement of women to their uteruses. These hopes and fears are farfetched. First, while Barrett may be a conservative, a supermajority Republican SCOTUS is not necessarily a supermajority conservative one. The Supreme Court has had a six-seat Republican majority as recently as the Obama years, when the Roberts Court included two George W. Bush appointees (Roberts and Samuel Alito), two George H.W. Bush appointees (Clarence Thomas and David Souter) and two Ronald Reagan appointees (Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy). Yet even before the Obama-appointed Sonia Sotomayor replaced Justice Souter, the Roberts Court was hardly had a conservative majority, let alone a supermajority. Souter was about as reliably progressive a vote as the typical Democratic appointee. Anthony Kennedy was famous as a ‘swing vote’, rather than a conservative one, and three years after Souter’s retirement, Chief Justice Roberts himself would vote with the court’s progressives to uphold the constitutionality of Obamacare.

[special_offer]

At the time he was appointed by George W. Bush in 2005, Roberts was sold to the base by conservative leaders in terms rather reminiscent of the way Barrett is being sold today, with a focus on Roberts’s surefire conservative credentials based on his wife’s involvement with the anti-abortion Feminists for Life. Yet Roberts has grown into a curiously Kennedy-like triangulator and joined the Trump-appointed Neil Gorsuch and every one of the Court’s progressives in the Bostock v. Clayton County decision earlier this year that redefined ‘sex’ in the 1964 Civil Rights Act to include sexual orientation — nobody’s idea of the original meaning behind the law, nor, until very recently, a plausible interpretation of the word itself.There is prima facie evidence, then, based on the historical record of modern Republican-majority courts and on the recent tendencies displayed by Roberts and Gorsuch, for thinking that even with Amy Coney Barrett on the court, SCOTUS will not move sharply to the right. But no one knows how a case that might overturn Roe would turn out, and having more Republicans makes the outcome more uncertain than it would be with more Democrats, who have been much more reliable progressives than the Republicans have been conservatives. Yet if Roe did go down, the result would not be the end of abortion in America anytime soon — the issue would go back to the states and ultimately back to the voters. No other country is exactly comparable to America, but if such heavily Catholic nations as Ireland and Poland have exhibited liberal tendencies in their abortion politics recently, even the most conservative American states are likely to be battlegrounds on the issue. In staunchly conservative Oklahoma, the roughly half of the state that has been designated as Indian country, thanks to another Gorsuch ruling, may well permit abortion even if a wide majority of the state’s voters oppose it. If conservatives on the Supreme Court can actually overturn Roe one day, the abortion wars won’t be over; they’ll be entering a new and wider phase, one in which states’ rights and Indian autonomy and the contradictory thinking of the public at large will make the fight much more complicated than it is now, when SCOTUS is the primary focus for both sides. (And the re-democratization of abortion politics, if ever Roe is overturned, may change the way in which the Court is politicized — but it won’t de-politicize the Court, whose constitutional authority always matters in the nation’s greatest controversies.) The American political system is much more dynamic and self-reactive than either left-wing or right-wing activists assume, caught up as they are in the passion of their commitments. A presidential victory is almost always a subsequent congressional defeat in midterm elections. A Supreme Court that notably conservative or progressive over a long period generates a popular backlash in the opposite direction. This is so because Americans are themselves divided and the Constitution partitions sovereign decision-making among separate branches with different time-scales for wielding power. The system is designed for conflict. That should never discourage partisans from fighting; quite the opposite. But it should temper the emotions of those given to apocalyptic or redemptive visions, and that in turn should lead one to look a little more coolly at the Supreme Court and its nominees. They matter, a lot — but only as pieces in a much bigger and more challenging game.