The history of rubbish can be scholarship, but the history of scholarship is often rubbish. The condescension of hindsight diminishes earlier habits of thought and behavior, especially when, as with freemasonry, they involve rolled-up trouser legs, coded handshakes and a curious blend of mysticism and matiness. Yet freemasonry was once a radical, even revolutionary, rite: to its adherents a harbinger of egalitarian, middle-class democracy, to its detractors a conspiracy of Jews, Satanists and sex addicts.

The Craft is a shadow history of modernity. Though it is more sober than most lodge meetings, it is, like its subject, ingenious and frequently bizarre. Freemasonry, John Dickie argues, is one of Britain’s ‘most successful exports’, along with other club activities like tennis, soccer and golf. Despite what you may read on the internet, freemasonry is ‘a fellowship of men, and men alone, who are bound by oaths to a method of self-betterment’. If this ideal of tolerant fraternity sounds modern, only without women, that’s because it is.

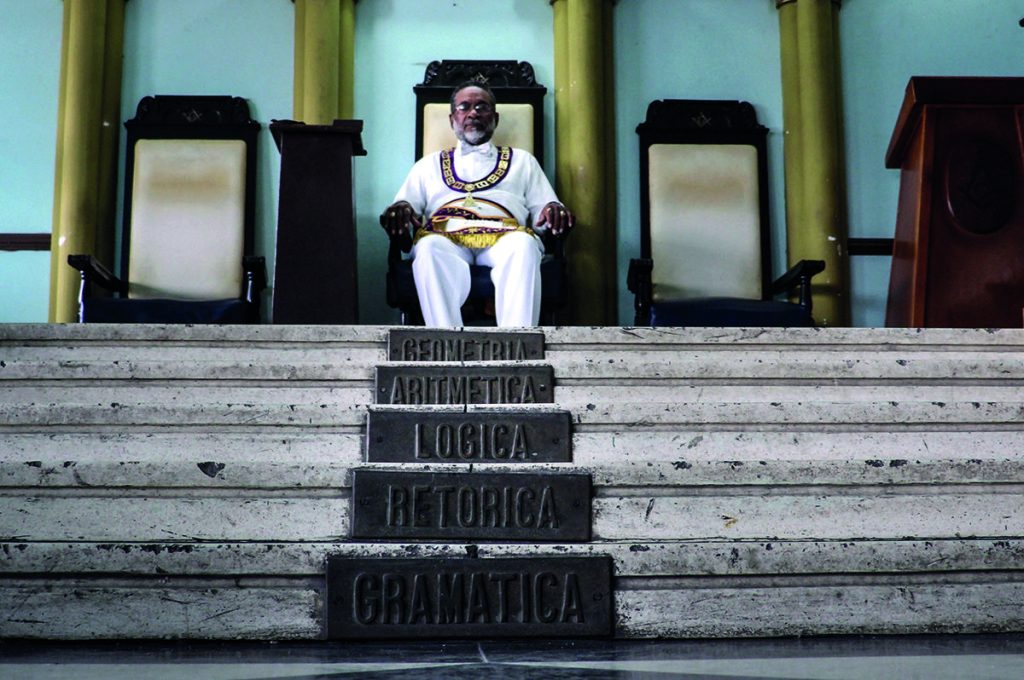

Freemasonry traces an ancient genealogy from Hiram, the Phoenician architect who built Solomon’s temple at Jerusalem, to the medieval stone masons who, as ‘free’ artisans, carried the secrets of their craft, the ‘Old Charges’, from job to job, cathedral to cathedral. But freemasonry is a child of the Renaissance and the Reformation. It speaks the universal language of reason and the particular languages of Protestant Hebraism and mystic Neoplatonism. Like golf and whisky, it emerged from Scotland and conquered the world.

In 1594, James VI of Scotland celebrated the birth of a male heir by commissioning William Schaw, his Master of Works, to build a new chapel at Stirling Castle. The ‘earliest Renaissance building of its kind’, Schaw’s Chapel Royal was, like the Sistine Chapel, built to the dimensions of Solomon’s Temple. Warming to his revivalist theme, in 1598 Schaw incorporated the masons’ sacred geometry and guilds (called ‘lodges’, after the temporary shacks on their building sites) into the old-new learning: the ‘art of memory’ once extolled by Cicero and the religious mysteries attributed to Hermes Trismegistus.

Scotland’s masonry of ‘operative’ stonemasons depended on trade secrets, so much so that the bond of masonry ran deeper than rivalry between Catholics and Protestants. The ‘speculative’ masonry that took off in London in the early 18th century attracted a broader public. In the golden age of the club and the coffee house, the gentleman amateur, the tradesman and the artisan all shared in ‘English liberty’. Outside, the landed aristocracy and the Anglican settlement still ruled. Inside, the ‘illustrious topers’ of urban England networked with Jews, Catholics and Protestant sectarians, politely speculating on the mystical backdrop to the Anglican universe and, judging from the drunken mason stumbling home in Hogarth’s ‘Night’ (1736-38), putting away patriotic doses of drink. Dr John Desaguliers, the scientist-theologian who codified the craft in these years, even managed a poem that ‘merged the Newtonian system, Masonic symbols and the Hanoverian monarchy into a single vision of universal harmony’: the Whig interpretation of spiritual history.

This ideal immigrated to America, where masons like Benjamin Franklin established the thoroughly respectable American lodge system, a Rotary Club of the soul. Later, the British carried it around the world. In the empire, the lodge was a link with home, but also common ground in societies divided by color, caste and class. As Kipling, a member of the Hope and Perseverance Lodge No. 782 in Allahabad, wrote in ‘The Mother Lodge’ from Barrack-Room Ballads (1890):

‘Outside — “Sergeant! Sir! Salute! Salaam!”

Inside — “Brother”, an’ it doesn’t do no ’arm,

We met upon the Level an’ we parted on the Square,

An’ I was junior Deacon in my Mother-Lodge out there!’

In the lodge, Kipling’s soldier is equal to ‘Bola Nath, Accountant’, ‘Saul, the Aden Jew’, ‘Din Mohammed, draughtsman’, ‘Babu Chuckerbutty’, ‘Amir Singh the Sikh’ and Castro the Catholic ‘from the fittin’ sheds’. Tolerance ended as the members stepped outside again. Kipling, Dickie reminds us, was a member of the same lodge as the young Nehru, whose Anglicized manners made him a member of the babu class that Kipling despised.

Freemasonry’s paths in Europe were, like Europe’s political history, a darker and more elaborate business. French masonic lodges banned ‘Jews, Mohammedans and Negroes’, though they made an exception for the Chevalier d’Eon who, as a celebrated transvestite, was one of the boys some of the time. The rites mutated and multiplied too. After a Jacobite named Andrew Michael Ramsay worked in the Crusades in an effort to reconcile the craft and Catholicism, a Scottish Rite developed in France, offering a ‘tropical forest’ of degrees and rituals. Next, Jean-Baptiste Willermoz added the Knights Templar and the new science of Mesmerism.

And then, according to Augustin de Barruel, the Illuminati, a failed Bavarian political club, executed a masonic plot to launch the French Revolution. In the century after 1789, this conspiracy theory became a weapon in the Catholic Kulturkampf against secular power. Sponsored by clerical fantasy and aristocratic resentment and fusing with antiJudaic conspiracy theories, it developed a life of its own, even summoning its own image.

In Italy the patriotic Carbonari adopted Barruel’s black legend as a handbook of revolution. This is one reason why Italians remain keen on masonic conspiracies. Another reason being curious incidents like the death of Roberto Calvi, the president of the Banco Ambrosiano, who was also known as ‘God’s Banker’ for his pecuniary maneuvers on behalf of the Holy See and was found hanged from a bridge in London in 1980. In France, where some 40 percent of civilian ministers of the Third Republic were ‘on the square’, the anti-clerical smut-peddler Léo Taxil, the author of Grotesque Cassocks and The Debauched Confessor, changed sides and became an anti-masonic smut-peddler, the author of Masonic Sisters and The Devil in the Nineteenth Century. French novels also supplied the material of the most successful forgery in history, and one of Russia’s few notable exports, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1905).

By 1925, the fantasy of a ‘Judeo-Masonic conspiracy’ was ‘bread-and-butter’ to Hitler’s first supporters. Some were freemasons, too, which must have been confusing for them. In 1926, the Old Prussian Grand Lodges voluntarily Aryanized their mythology and, in 1932, Germany’s Grand National Lodge declared itself to be völkisch. This did not stop Hitler from following Mussolini’s lead and banning freemasonry. In 1934, a recruit to the SS’s intelligence agency demonstrated his organizational skills by compiling a central list of German freemasons. His name was Adolf Eichmann.

Post-war freemasonry echoes these historical schisms between Anglophone and non-Anglophone traditions, and between Protestants and Catholics. In 1983, Cardinal Ratzinger, the future Benedict XVI, wrote that Catholic freemasons are ‘in a state of grave sin and may not receive Holy Communion’, but in 1993, the Southern Baptist Convention ruled that membership of a lodge was a private matter. In the English-speaking world, freemasonry remains so reasonable as to be mocked as ‘the mafia of the mediocre’, but in Italy, the P2 Lodge was the incubator of conspiracy to murder and defraud.

Freemasonry’s promise of tolerance, Dickie writes, has been fulfilled in the truly ecumenical lodges of India, but it still exacerbates paranoia in Muslim societies. In Pakistan, where General Zia-ul-Huq banned freemasonry in 1972, Kipling’s old lodge is now a government office. The charter of the Palestinian Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) lists freemasonry along with the real danger to society, the Lions and the Rotary Clubs, as ‘networks of spies’ created by the Jews who, not satisfied with causing the French Revolution, now roll up their sleeves as well as their trousers to ‘destroy societies and promote the Zionist cause’. This would be almost quaint, were it not that the internet is seething with this sort of trash.

John Dickie’s previous book was Cosa Nostra, the first history of the Sicilian mafia to be written by an outsider. The Craft is well-crafted and sensible in judgment. Dickie makes good use of English archives which were only opened in recent decades, and he avoids laying on the conspiracy-theory material with a trowel, whether operative or speculative.

By offering a new way of socializing, freemasonry laid the foundations of our egalitarian and commercial society. This, as we now know, is perfectly pleasant but, lacking degrees of initiation higher than a black AmEx card and the velvet rope of the VIP room, it sometimes loses its sense of purpose. Freemasonry offers just that to its practitioners, but also to its enemies, who mistake its hopes for their own fantasies of power.

‘I am utterly opposed to it and to the influence of other secret organizations because I believe them to be a deeply corrupting influence on society,’ a Labour party backbencher told the House of Commons in 1988. ‘Masonic influence is serious.’

Who was that brave speaker of truth to power? Jeremy Corbyn, the future leader of the Labour party.

This article is in The Spectator’s September 2020 US edition.