The recent high-profile departures at the New York Times of editorial page editor James Bennet and opinion writer Bari Weiss have left some on the business side of the news industry scratching their heads. Both exited amid ideological turmoil that Weiss detailed in a letter of resignation to the Times’s publisher A.G. Sulzberger, describing the ‘hostile work environment’ she endured at the hands of fellow editors and staffers. They were wholly intolerant, she said, of her role as a ‘centrist’ at the paper. Bennet, said Weiss, had led the effort after President Trump’s election in 2016 to bring in ‘voices that would not otherwise appear’ in the Times.

But what of Sulzberger, whose prime duty is to New York Times shareholders and therefore to the paper’s bottom line? How does the top executive justify alienating swathes of Times customers and potential subscribers who may be sympathetic to, or even merely curious about, ideas beyond what Weiss described as ‘our 4,000th op-ed arguing that Donald Trump is a unique danger to the country and the world’?

The overlooked truth is that there is considerable financial incentive for the Times to limit the scope of discussion. This business angle may foretell what to expect from the Times going forward.

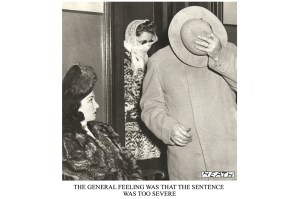

It’s a product of how the business of news has evolved in recent years. Advertising revenue has been hurtling downhill for some time and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated that decline. In the first quarter of this year, the Times’s ad revenue fell 15.2 percent year-over year. In May, the Times announced that it expects advertising revenue in the second quarter to fall even more dramatically, by between 50 and 55 percent.

And yet the company’s stock price continues to climb. It is now priced in the $46 per share range. Its all time high of $52 per share, set in 2002, is within reach. This steady climb marks a remarkable recovery from a low of about $4 per share in 2009.

These strong numbers are a product of the Times’s successful digital subscription business, which has grown rapidly in recent years. Last year, the publisher announced the goal of reaching 10 million subscribers by the end of 2025. In February the paper announced it had hit the halfway mark a year early. In the first quarter of this year the Times added an impressive 587,000 new digital subscribers, bringing its total subscriber base to more than six million, some 85 percent of which are online-only.

In the past, when advertising was the main driver of revenue, the goal was to reach the widest possible audience. Now, though, the business model demands the paper focus on catering to a narrow but passionate segment of the readership base. That segment increasingly accounts for the bulk of the Times’s income — and it prefers a narrow, left-wing editorial line.

A 2017 study of data from hundreds of major media sites conducted by Piano, a leading provider of metered paywalls for the news industry, found that for most media outlets the bulk of digital subscription revenue is driven by a small percentage — between 2 and 12 percent — of readers. Piano calls them ‘super-fans, super-users, direct and dedicated, the invested, and loyalists’.

‘Being able to serve and monetize this relatively small part of the audience now makes all the difference between success and failure,’ the study concludes.

While the Times’s loyal subscriber base grows, its overall readership is growing even faster. ‘The rapid increase in subscriber numbers means that, if anything, an even smaller percentage of the audience is driving the bulk of the revenue,’ says Mark Thompson, CEO of the Times.

This relatively small base of ‘loyalists’, who are so fundamental to the Times’s business model, stand largely on the left of the political spectrum.

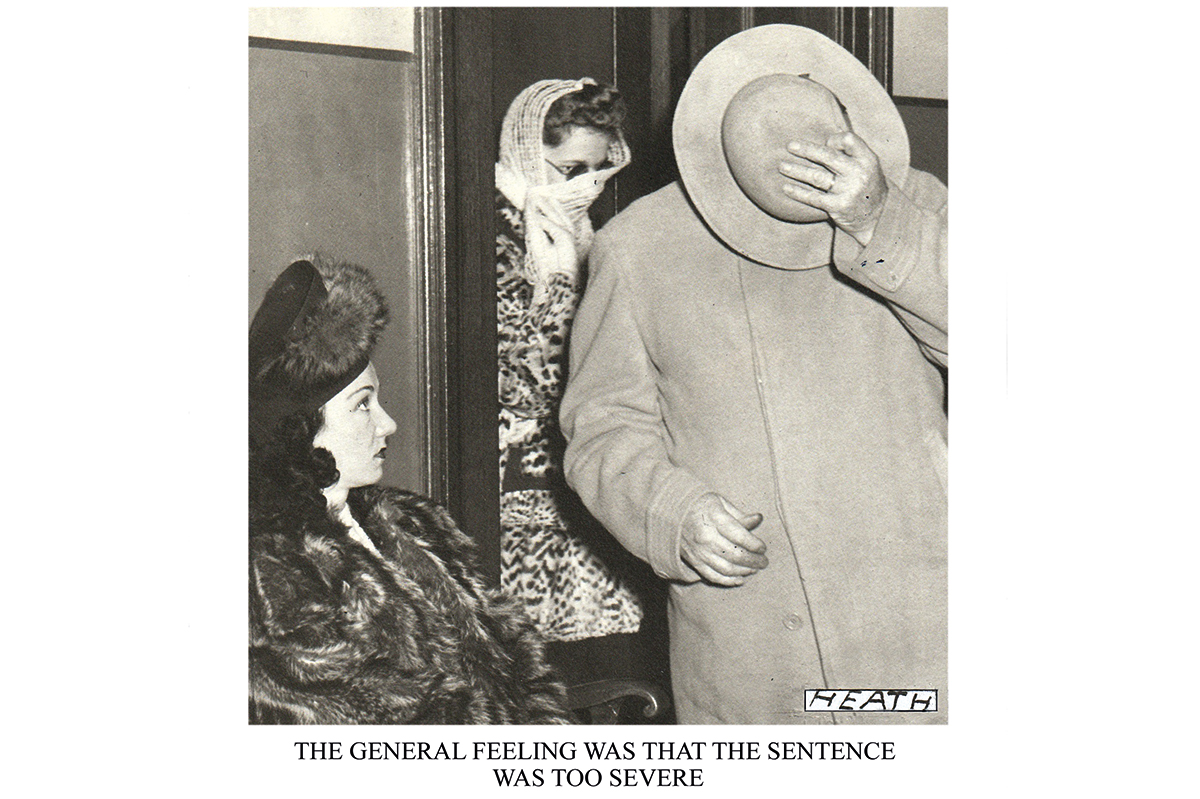

The Times’s public editor, Liz Spayd, addressed the question of the paper’s political leanings in a 2016 column. She was unsuccessful in uncovering the official ‘proprietary’ numbers on the ideological breakdown of the Times’s subscriber base, but noted that ‘on most days, conservatives occupy just a few back-row seats in this giant liberal echo chamber’.

Should the paper ‘write off conservatives and make a hard play for the left and perhaps center left,’ Spayd asked, ‘or has that already happened?’

Spayd notes a 2014 Pew Research survey which found that 65 percent of Times readers leaned to the left, and only 12 percent leaned to the right. Considering the heightened polarization in media today, it’s likely that those numbers now skew even further left, and that the ‘loyalist’ subscribers are drawn from that audience. Spayd was on to something. Her job at the Times was subsequently eliminated.

The phenomenon of leftward drift and loyalists came starkly to light after President Trump’s election in 2016, which triggered a new surge in subscriptions. In 2017, Times executive editor Dean Baquet acknowledged in a CNN interview the impact Trump has on revenue. ‘Every time he tweets, it drives subscriptions wildly,’ Baquet said. In 2018, the Financial Times reported that the Times was still ‘riding the high of the so-called “Trump Bump”’.

[special_offer]

The President often belittles the paper as the ‘failing New York Times’. The Times often returns fire. The Vox columnist Jeff Guo described this approach as ‘a great way to pile even more liberals onto the Times’s subscriber bandwagon’.

In recent years Thompson has tried to push back against the contention that subscriptions are driven by opposition to Trump, citing diversification among subscribers ‘geographically and also in terms of race and ethnicity’. But he has provided no evidence of any political diversification.

In her resignation letter, Bari Weiss confirms that stories are ‘chosen and told in a way to satisfy the narrowest of audiences’. Sulzberger’s apparent comfort with the departures of Weiss and Bennet affirms why this is the case. For the New York Times, what Weiss calls ‘self-censorship’ has been good for business. As long as the stock price and paid subscriber numbers keep rising, expect that newspaper’s ideological transformation to proceed apace.