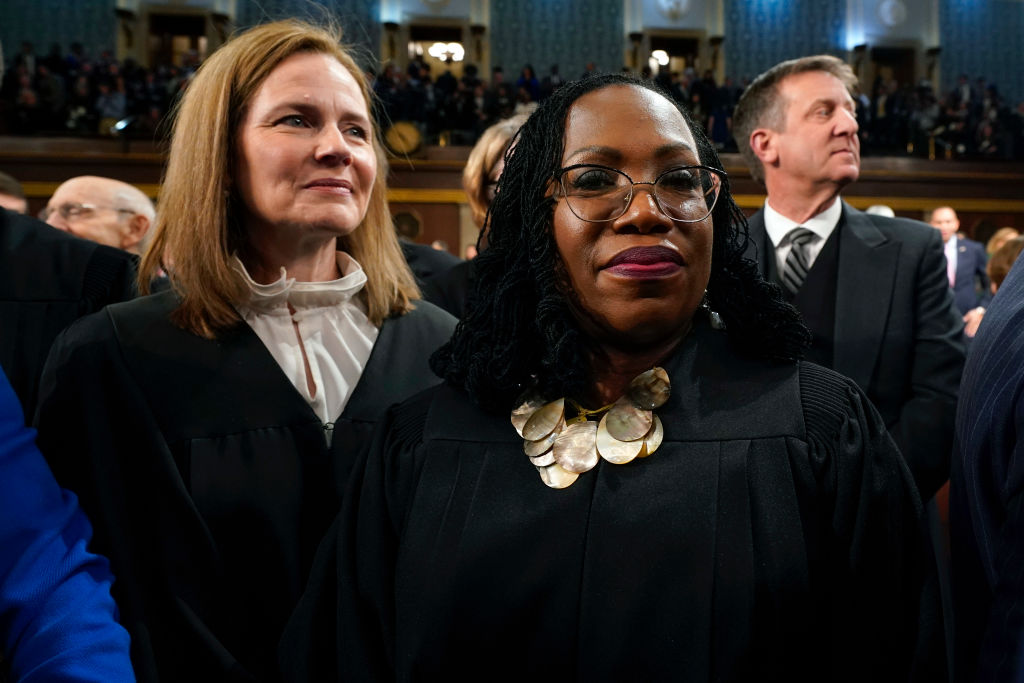

On the day after the presidential election, Amy Coney Barrett, now beginning her career as a Supreme Court justice, will hear oral arguments in one of the most significant civil rights cases to come before the Court in decades. The case is Fulton v. Philadelphia.

The point of contention in the case could hardly be more sensitive, since it pits the protection of religious freedom against the interests of same-sex couples — and the context is the foster care of children. Its journey to the nation’s highest court has been long and bitter.

In 2018, city officials in Philadelphia insisted that the Catholic Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s foster care agency certify same-sex married couples as foster parents. This is something the archdiocesan agency couldn’t do, since it is inconsistent with Catholic teaching on marriage. The recent headlines about Pope Francis’s support for civil unions are irrelevant here: the Pope has been consistent in his fidelity to Church teaching on marriage.

Any attempt to present this as an example of Catholic anti-gay bigotry immediately runs into inconvenient facts. Catholic Social Services in Philadelphia does not oppose certifying and working with gay people. It accepts children for foster care placement regardless of race, sex, creed, disability or sexual orientation. And if it is approached by a same-sex married couple interested in fostering — which it never has been — then it will cheerfully refer the couple to another agency.

Nonetheless, the city stopped referring children to the agency and refused to renew its contract. Its 200 years of care for disadvantaged children counted for nothing, it seemed. At this point long-time foster mothers and their foster care agency filed suit. Another inconvenient detail: the two mothers, Sharonell Fulton and Toni Simms-Busch, are both single women of color. Fulton has fostered over 40 children while helping them maintain a relationship with their biological parents. She and Simms-Busch have been described as ‘foster care heroes’. They’re also Catholics who want to work with an agency that shares their faith.

In an amicus brief I filed in the Supreme Court, former foster children and foster/adoptive parents share their positive experiences with Catholic-run adoption and foster care agencies. These agencies aren’t mere matchmakers but offer continuous supports and services to children, their foster or adoptive parents, and their biological parents (where reunification was possible). Foster mother Winnie Perry notes, for example, that the agency staff at Philly’s Catholic Social Services were there for ‘anything I couldn’t handle’. Adrienne Cox, former foster child to Perry, credits the agency with offering something ‘unique’. Cox believes that the agency’s expectations of its foster parents made her childhood experience more stable and satisfying than that experienced by other foster children.

It’s a grim fact of life that many biological parents fail their children. Allowing Catholic agencies to respect their Church’s teaching on same-sex marriage — which makes little or no difference in practice — harmonizes policy interests and Constitutional guarantees of religious freedom. And it keeps services flowing. Chief Justice John Roberts and newly-confirmed Justice Barrett understand how important a placement agency is from personal experience: they have both themselves adopted children.

Fulton is also a crucial case for religious liberty in America because the Court may revisit its rather confusing 1990 ruling, Employment Division v. Smith, that religious objectors are not constitutionally entitled to exemptions from neutral, generally applicable laws.

Smith has proved unworkable in practice. Fulton shows why. The lower courts reviewing Fulton ignored evidence that the city of Philadelphia targeted the Catholic agency and that its anti-discrimination policy was riddled with exceptions. Put simply, the city’s determination to punish the agency confirms suspicions that Smith inadvertently emboldens public officials to restrict religious freedom using a pretext of neutrality. That is why the petitioners are asking the Court to clarify that the government can’t use seemingly neutral anti-discrimination laws to shut religious believers out of the business of caring for the needy in their midst.

At this point you may be wondering: what about the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling that there’s a constitutional right to same-sex marriage? Doesn’t that mean that the petitioners’ case is dead on arrival?

[special_offer]

It doesn’t, actually. The author of the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy, recognized that many Americans’ conception of marriage is formed by sincerely held religious beliefs. He cautioned that ‘the First Amendment ensures that religious organizations and persons are given proper protection as they seek to teach the principles that are so fulfilling and so central to their lives and faith and to their own deep aspirations to continue the family structure they have long revered’. Philadelphia’s rigid demand that all private groups endorse same-sex marriage in order to place foster children in loving homes, disregarding religious freedom, carelessly passes over Kennedy’s admonition.

During her confirmation hearings, Justice Barrett explained time and time again that the Supreme Court is not a policymaking body. The justices instead must safeguard the guarantees found in the Constitution and faithfully interpret the law. And sometimes it is unpopular. One need only think back to the fury generated in some parts of the country by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which ruled that segregation in schools was unconstitutional.

If the Justices do their job in Fulton by harmonizing the interests of same-sex couples with religious freedom, they probably won’t receive accolades from the ACLU; we can expect some nasty abuse to be flung at Justice Barrett in particular. But they will be preserving the guarantees written in the Constitution and, in the process, join the ranks of Sharonell Fulton as foster care heroes.