It was 51 years ago, in the Hôtel du Cap d’Antibes, that I first met the man whose opioid product has, along with other prescription opioids, killed more than 200,000 Americans. Mortimer Sackler looked old even back then. He had a Noo Yawk accent and, even though we’d never been introduced, approached me after a tennis match I had just lost with some unsolicited advice: ‘You need to calm down. Take a tranquilizer’ — or words to that effect. (I had been feuding throughout the match over atrocious line calls with a French ref who was being intimidated by the pro-French crowd.)

Although I do not gladly take advice from strangers, I thanked him nevertheless and told him that pills were not the answer but good refereeing was. Then a funny thing happened. A couple of weeks later, his Austrian wife Gheri, his second, suddenly left him and he had a sort of breakdown in the hotel. When I saw him being taken to the hospital, I remember thinking that he must have taken his own advice and had overdosed.

I got to know Mortimer better later on when he married a very nice Catholic girl, Theresa, who was studying to become a nun. They married and had children and she eventually became his widow. They moved to Gstaad, built two chalets near the Palace hotel and joined the so-called chic crowd. (Chic, my arse.) Mortimer always invited me to his backgammon game, but over 30 or 40 years I think I played once, perhaps twice. He kept the stakes very low, and in those days I was looking for action, not distraction.

Sackler was always friendly, but like a typical New Yorker was too familiar and handed out advice like paper hankies during a flu epidemic. I was particularly appalled when I ran into him and his older brother once in front of the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and heard them call Alexander Solzhenitsyn a psychopath. Sackler was very left-wing when it came to politics, but I assume less so when it came to company profits.

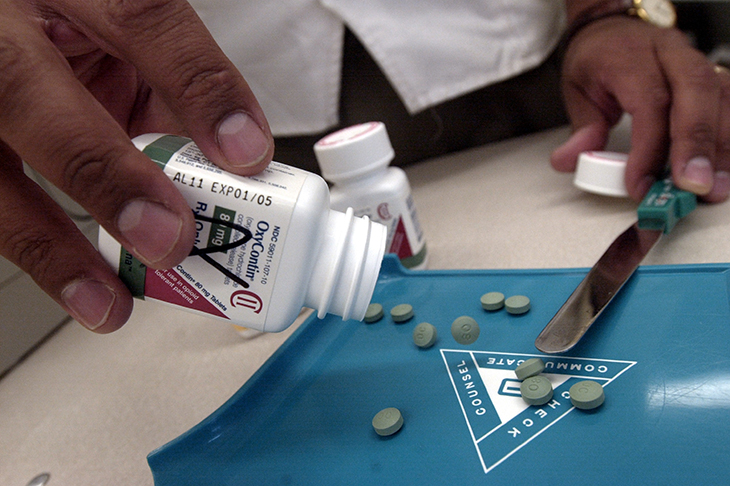

His family is now in deep trouble. They’re alleged to have shifted hundreds of millions of dollars from the business, Purdue Pharma, to themselves through offshore entities, and the state of New York has sued them. The state wants to claw back funds that it alleges were transferred from Purdue to private or offshore accounts in anticipation of lawsuits. The Sacklers say the charges are false.

My only regret is for Sackler’s widow Theresa, who had nothing to do with the marketing for OxyContin, which allegedly ignored evidence that the drug was more potent than heroin and that it was being abused. Listing her as one of the beneficiaries is misleading, because although she inherited her husband’s estate she had absolutely nothing to do with the running of his company. Throughout her marriage she was busy bringing up children, managing their various houses and doing charity work.

Monsieur Balzac wrote rather hyperbolically that behind every great fortune there is a great crime. He sure is right when it comes to the Sacklers. They profiteered from the plague they knew would be unleashed, and that’s a crime in my book.

What is worse is the hypocrisy. These bums thought nothing of enslaving people with the drugs that eventually killed them, as long as they kept up appearances by throwing a few millions to museums and having their names engraved on the walls. The Met has a Sackler wing. This is a tale of extravagant greed and a shocking lack of morality. I don’t know any of the generation after Mortimer, but I think that a son-in-law in Gstaad once rudely asked me in a loud voice at a party who I was. ‘Look me up in the Almanach de Gotha, asshole,’ I answered just as rudely. I should have cooled the arrogant bastard.

In my view they should have their dirty money taken away — like drug dealers. The problem is the Sacklers have expert advice when it comes to hiding assets and using the law to protect themselves. The state does not. I was once hitting balls indoors when Mortimer Sackler asked me to play a couple of games with him. If memory serves, he was playing with George Soros in the next court and someone pulled a muscle. Mortimer couldn’t play at all, so I pretended to miss every ball and then banged the ground in feigned rage while I dropped a game to him. My wife was watching and told me not to make it so obvious. I was later told, although I never heard it myself, that Mortimer had told people I was a bad sport and could not take defeat.

How could one so blind to his own shortcomings — and not only where tennis was concerned — be able to think up as evil a plan to enrich one’s self while killing thousands of people? Perhaps I am a bad sport after all, because I like to play by the rules. Make them give it all back.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.