Rome

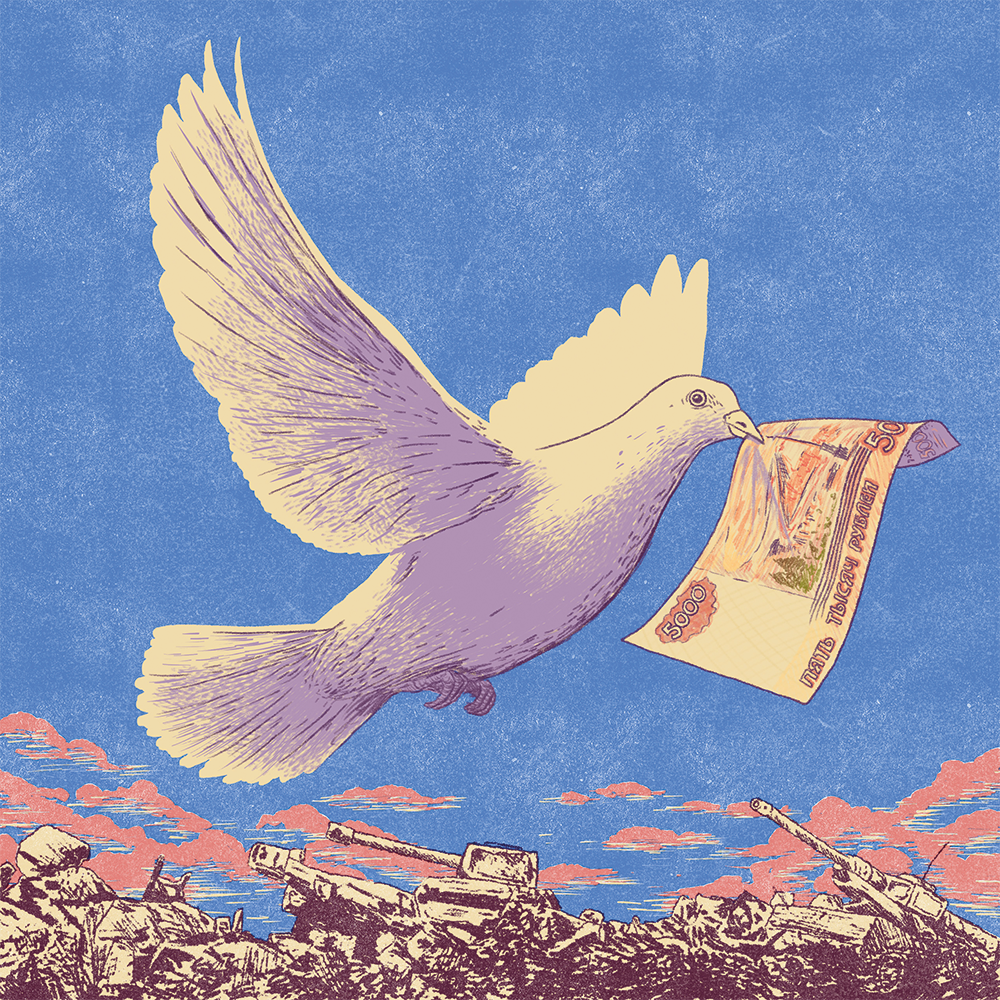

Will peace in Ukraine also prove to be a great deal for US business? Vladimir Putin would certainly like Donald Trump to think so. Within days of Trump’s election victory last November, the Kremlin ordered major Russian corporations to prepare detailed proposals for economic cooperation with Washington. Coordinating these efforts were Maxim Oreshkin, deputy head of Putin’s presidential administration, and Kirill Dmitriev, the US-educated Harvard, Stanford and Goldman Sachs alumnus who heads Russia’s sovereign investment fund.

According to a major US investor in Russia who eyes a postwar return to the market, among the major Russian corporations setting out potential deals for US companies were Russia’s atomic energy agency Rosatom, the oil company Rosneft; aluminum giant Rusal, and gold mining conglomerate Polyus.

“A permanent economic quarantine of a nation of Russia’s size and resources is a fantasy,” says the investor, who is also a long-term Trump donor. “The question is not if, but how and under what conditions, we re-establish ties… [Trump] rightly wants American companies at the forefront of that.”

A year later, and the Kremlin’s efforts to convince the White House to view Russia not as a military threat but as a land of huge business opportunities are bearing fruit.

Since February, Dmitriev has been Putin’s special envoy to Washington and has formed a close working relationship with Trump’s own envoy and golfing partner Steve Witkoff and, more recently, the President’s son-in-law Jared Kushner. “The presence of Dmitriev means that the White House is being engaged commercially more than politically,” says Chuck Hecker, author of Zero Sum, a history of western business in Russia. “Dmitriev’s purpose is to dangle business deals in front of the Trump administration.” And even as Dmitriev, Witkoff and Kushner engage in shuttle diplomacy over a final peace deal in Ukraine, US businesses have been secretly positioning themselves to take advantage of a new world order where sanctions on Russia are lifted and business deals flow.

Early signs of US receptiveness to a new business-based strategy came in July when the head of Russia’s Roscosmos space agency, Dmitry Bakanov, visited NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston. Russia’s once-thriving multimillion dollar space cooperation with NASA had been winding down for years. But Bakanov came with offers of cooperation on manufacturing new generations of spacecraft for NASA, Boeing and SpaceX.

One of the Kremlin’s biggest offers to Trump has been to dangle joint oil and gas exploration projects in the resource-rich Arctic, as well as bringing US oil companies back on board in Russian oilfields where the Kremlin had previously squeezed out foreign partners.

According to a recent investigation by the Wall Street Journal, ExxonMobil senior vice-president Neil Chapman has met Rosneft boss Igor Sechin, Putin’s former private secretary, in the Qatari capital Doha, to discuss Exxon’s return to the massive Sakhalin project, an investment stranded after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Moreover, veteran Putin associates and personal friends Gennady Timchenko, Yury Kovalchuk and Boris and Arkady Rotenberg have been “offering US counterparts gas concessions in the Sea of Okhotsk, as well as potentially four other locations,” claimed the WSJ, quoting senior European officials.

On the other side of the Atlantic, old friends and associates of the Trump family have also been getting in on the act. Gentry Beach, a college friend of Donald Trump Jr. and campaign donor to his father, has been in talks to acquire 9.9 percent of an Arctic liquefied natural gas (LNG) project with Novatek, Russia’s second-largest natural gas producer, which is partly owned by Timchenko. Beach confirmed that his company America First Global “actively seeks investment opportunities that strengthen American interests around the world” and said that partnering with Novatek would “strongly benefit any company committed to advancing American energy leadership.”

US investors are also circling distressed Russian assets such as the Nord Stream pipeline, which was partly destroyed by saboteurs in September 2022, and overseas assets of Lukoil, Russia’s largest private oil company, which was sanctioned by Washington in October. Todd Boehly, a billionaire investor in Exxon, has explored buying assets owned by Lukoil. (Boehly is, as chance would have it, now co-owner of Chelsea Football Club, which used to belong to the Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich.) Then there’s Miami-based investor Stephen P. Lynch, a Trump donor who is seeking a US Treasury Department license to buy the Nord Stream 2 pipeline from its owner, a Swiss subsidiary of Russia’s Sberbank, if it comes up for auction in a Swiss bankruptcy court. To help the deal through Lynch has hired lobbyist Ches McDowell, a friend of Don Jr., on a $600,000 contract over the next six months, the WSJ reported.

“If a resumption of legal trade and investment is conditioned on the war ending on terms that Ukraine accepts, and the war staying ended, then it’s a good thing and I hope that it succeeds,” says Mike Calvey, co-founder of the Baring Vostok investment company, who was imprisoned in Russia for two months in 2019 after a business dispute. “It’s the right approach to create an incentive for Russia to agree to whatever last concessions are needed.”

But there are at least two fundamental problems for US businesses in scoring big in a postwar Russian market. One is that Russian companies, banks and individuals are currently entangled in a thicket of US and EU-imposed sanctions, some imposed by Congress, others by the European parliament and yet more by US presidential decree and by the nonstatutory rulings of various European and British law enforcement bodies. Those sanctions will take a long time to unravel, even if some kind of peace deal is struck over Ukraine. It’s unclear whether European lawmakers will be in any mood to reward Russian aggression and return to business as usual. “Europe politically remains in punishment mode on Russia,” says Hecker. “But the European business community, I think, is probably as eager to go back as the Americans. And if Trump moves to set American business free in Russia, the Europeans will want the exact same treatment from its governments.”

The other major problem in the Kremlin’s rosy vision of an economic reset is the recent specter of Russian bad faith and outright theft of the assets of international companies in the aftermath of the February 2022 invasion. More than 1,000 international companies announced withdrawals from Russia, an exodus that represented one of the most rapid and sweeping corporate retreats in modern history. Giants such as McDonald’s, which sold its business to a Siberian licensee, Ford, General Motors and Shell made clean, albeit financially painful, exits. Meanwhile, the French car giant Renault sold one of its major assets, its controlling stake in Russian carmaker AvtoVAZ, in 2022 for a symbolic one ruble. But many western multinationals found themselves caught in a process of corporate hostage-taking. The Russian government, through presidential decrees and court rulings, effectively legalized the seizure of assets from companies based in “unfriendly” countries.

In the summer of 2023, the Russian state took control of the subsidiaries of Danone and the Danish brewer Carlsberg, which called the move “illegal” and has been locked in a legal battle with the Kremlin ever since. In the same year, Fortum, a Finnish state-owned energy company, and Uniper, its German counterpart, had their Russian assets seized by decree. This move sent a chilling message: not even critical energy infrastructure owned in part by European governments was safe.

“There’s a 25-year history of dead bodies, broken deals and lost money of anyone doing business in Russia,” warns Sir William Browder, once the largest foreign portfolio investor in Russia before his company was dispossessed and his lawyer Sergei Magnitsky killed in jail. “For a bunch of new guys to show up and hope their experience is going to be somehow different is the height of naivety… they’ve proven themselves to be unworthy of investment of any kind. And why would it be any different in the future?”

Some Republicans have voiced alarm over the White House’s enthusiasm for re-setting economic relations with the Kremlin. “How can you discuss future trade and investment when the outstanding claims from the last chapter are met not with arbitration, but with confiscation?” asked Texas Representative Michael McCaul, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, earlier this year. “Normalization cannot be a one-way street where Russia enjoys the benefits of global commerce while flouting its most basic rules.”

Nonetheless, it’s clear that top White House insiders Witkoff and Kushner and even Trump himself have bought into a vision of what Russian presidential advisor Yuri Ushakov calls “the intersection of US and Russian economic interests.” Talks on energy, Arctic exploration, rare earth metals and minerals are the kind of economic deals with big numbers and conveniently distant deadlines that make for big, attention-grabbing headlines. Smaller-bore, more nuts-and-bolts sectors of potential business cooperation such as pharmaceuticals, banking, retail and automotive have so far not been a part of the Trump administration’s public rhetoric.

For the most part, European governments are still talking about increasing sanctions on Moscow, not easing them. After four years of refusing to truly sanction the purchase of oil and gas from Russia, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced in December that the continent would cease its imports by the end of 2027 – as well as tightening its restrictions on so-called “shadow fleet” tankers that transport Russian oil. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and the Baltic leaders remain unequivocally opposed to any kind of reset with the Kremlin, with Tusk declaring in Riga, “there can be no business with a gangster state. Full stop.”

Yet there are signs that a few Europeans are following Trump’s lead in lining up for a postwar, post-sanctions world. “The war will one day end, and we will need a framework for peace and prosperity,” Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a persistent critic of EU sanctions, told the European parliament in January 2025. “A complete economic Iron Curtain benefits no one in the long run.” Germany’s right-wing AfD party, rising fast in the polls, has even called for a return to buying cheap Russian natural gas. Deputy AfD leader Alice Weidel promised that “we will once again engage the Nord Stream.” And even Michael Kretschmer, who leads the German state of Saxony for the centrist Christian Democratic Union (CDU), in May called for the damaged pipelines to be repaired to keep the option of cheap gas open “once hostilities end.”

So far those voices are outliers. As Browder points out, “Russia continues to be fighting a hybrid war with Europe. Russia is digging up internet cables. They’re assassinating people. They’re flying drones into Poland. They’re flying MiGs into Estonia… it’s not like they’re all of a sudden going to become a peaceful neighbor.”

Trump may have bought into the Kremlin’s vision of a future of cooperation. But the path to rebuilding trust with Europe will be much rockier.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 22, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply