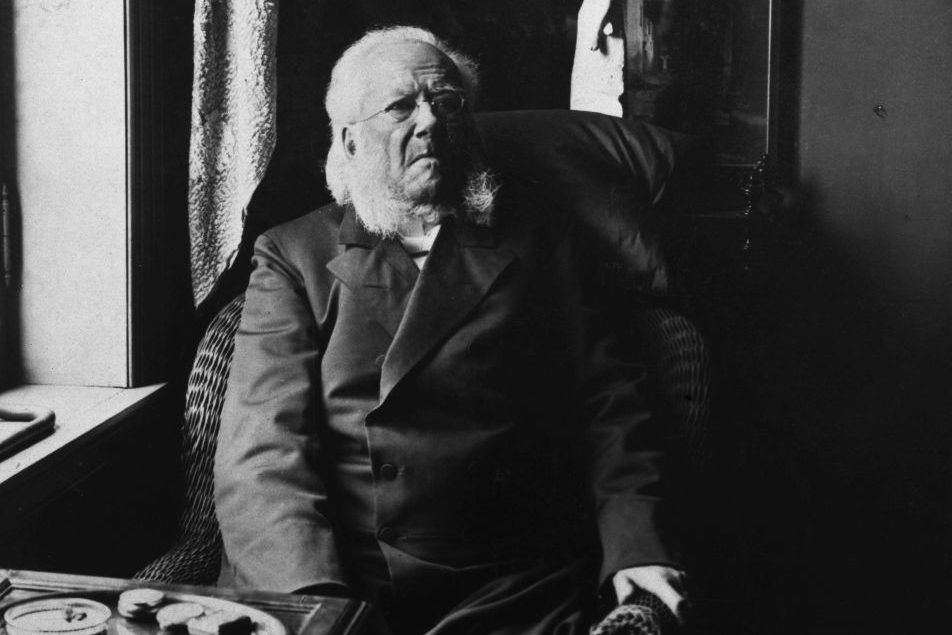

Suddenly it’s Ibsen season in Washington, DC. It’s true that only Shakespeare’s plays are performed worldwide more often than Henrik Ibsen’s. But to have two of the great 19th-century Norwegian playwright’s works running at once in the nation’s capital is unusual. And the works in question – An Enemy of the People and The Wild Duck – deliver contradictory messages. Together they say something not only about the state of the arts in Washington, but also about the state of the liberal mind.

Politics is very much a presence on the capital’s stages. The city’s two main Shakespeare organizations, the Shakespeare Theatre Company and the Folger Theatre, last year presented seasons heavily influenced by the presidential election. Folger’s Romeo and Juliet made the Montagues and Capulets representatives of rival political parties, though the point was rather lost in a messy production that also tried to be trendy.

The STC was subtler, with a lineup that spoke to liberal electoral anxieties. Babbitt, based on the Sinclair Lewis novel, is partly the tale of a demagogue’s rise. Yet there was also a post-election production of Leopoldstadt, Tom Stoppard’s reflection on the lives of Viennese Jews as bourgeois anti-Semitism made way for Nazi violence, that spoke to the darkest fears, or the most overheated rhetoric, of theater-going liberals.

Knowing the politics of the capital and its theaters, one isn’t surprised to see Enemy revived. On the surface, Ibsen’s play about a scientist who discovers an environmental hazard that threatens to upend the economy of a resort town – and is met with furious denunciations by the authorities for his discovery – seems like a parable flattering to many a crusading liberal. And sure enough, the program for this production drew a parallel between Ibsen’s protagonist, Dr. Thomas Stockmann, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, to liberals the hero (and to the right, the villain) of America’s Covid response. “At least one congressman has labeled Dr. Fauci an ‘enemy of the people’,” the program noted. It’s a phrase Trump bandied about, too.

Yet Ibsen was no mere liberal, although the extent of his distrust for ideology is masked by Amy Herzog’s “new version” of Enemy, which debuted on Broadway last year and was staged in DC last month. The authentic Stockmann, as Ibsen wrote him, says near the play’s end: “I only want to knock a few ideas into the heads of these mongrels: that the so-called liberals are free men’s most dangerous enemies; that party platforms wring the necks of every young and promising truth; and that party-political-opportunism turns morality and justice upside down…”

He adds: “We have to get rid of the party bosses – a party boss is just like a wolf – a ravenous wolf,” words that wouldn’t comfort an audience that might include Chuck Schumer or Nancy Pelosi. Ibsen’s Stockmann ends up something of a Nietzschean, declaring himself “one of the strongest men in the whole world,” an heroic individual standing against party and press, rejecting the hypocrisies of those who claim to be altruistic progressives or, in the case of radical newspapermen, revolutionaries.

Herzog’s Stockmann, as presented in DC, is an altogether tamer animal whose concluding words instead hymn the power of imagination to lead us to a better world. Ibsen has been rewritten to sound like Kamala Harris – the party bosses have won. Do DC theater-goers appreciate the irony?

The point in An Enemy of the People is to stand by the truth, no matter whom it offends or however great the suffering one endures on account of doing so. Stockmann loses his job and becomes the most hated man in his community rather than compromise his message. So what is the point of a theater company presenting the play in a compromised form? Ibsen was concerned about something more than the purity of a town’s water supply. Liberals of his own time were scandalized; it’s a testament to his genius that he remains ideologically indigestible.

Something of his intended meaning does come through despite the censorship, however, and even a viewer less skeptical of progressive than myself might wonder, watching this Enemy, whether a figure as demonized by the political authorities and progressive journalists as Stockmann is better matches Fauci – a state employee – or the independent critics of government Covid policy who suffered for their skepticism, like the now-vindicated Dr. Jay Bhattacharya.

Then there’s the other Ibsen lately on stage in Washington: STC’s production of The Wild Duck. For all that STC operates in keen awareness of the city’s politics, artistic director Simon Godwin clearly has an interest in art for its own sake, which is in evidence in productions of Chekhov and Ibsen he’s directed recently. The Wild Duck (1884) seems to have been Ibsen’s response to those who took the wrong lessons from Enemy (1882): the truth-telling radical who drives the action of The Wild Duck is a fanatic who brings ruin to his dearest friend. Gregers Werle is a man who sees it as his calling to liberate goldfish from their bowls, to borrow an image from G.K. Chesterton. But instead of allowing them to swim free, men like Werle only reveal that creatures accustomed to captivity cannot survive in an atmosphere of pure truth. They need what Werle’s philosophical opponent in the play, a doctor named Relling, calls “the life-lie.”

A would-be savior can be a calamity for the very people he intends to save, and Werle is a man of purest enlightenment philosophy and romantic longing for authenticity – a liberal or progressive, in other words. His idealism is diabolical, leading an innocent to suicide and revealing the inability of ordinary people to live the lives an idealist thinks worth living. Ibsen and Nietzsche were contemporaries, and neither had much direct influence on the other. Yet Ibsen is Nietzsche on the stage – even the politically progressive stage of Washington, DC.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply