Death falls from the sky in Denis Johnson’s 116-page novella Train Dreams (2011) in the form of “widowmakers,” broken tree limbs that can strike heedless loggers. Death burns through forests and arrests the heart of a young man hauling sacks of cornmeal; it rots through the wounded leg of a pedophile; it takes Robert Grainier in his sleep in November of 1968: “He lay dead in his cabin through the rest of the fall, and through the winter, and was never missed.” But Train Dreams, often hailed as a “miniature masterpiece,” is not a story of defeat: it is an elegiac love letter to the unobserved life of the American frontier worker who, though left behind by the steady march of progress, endures with quiet grace.

Now, director Clint Bentley (Sing Sing, Jockey) has faithfully adapted the novella for the screen. He co-wrote the screenplay with Greg Kwedar.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Grainier, masterfully played by Joel Edgerton, finds work as a railway laborer in the Pacific Northwest, logging 500-year-old trees to make way for the railroad and building bridges. His work keeps him from his home in Fry, Idaho, where his wife, Gladys (Felicity Jones), and young daughter, Kate, live in a cabin in the woods. It is a time of speed and rapid change; the old must make way for the new. A railwayman declares that a new wooden bridge has shaved miles off the old train route. A brief shot, set in the future, shows Grainier looking at the steel highway bridge that will soon make his labor irrelevant. Later in the film, he watches the moon landing on television.

Grainier meets a quirky cast of characters, the kind that line of work inevitably attracts. But as he grows older and two-man saws are replaced by chainsaws, the work becomes more solitary, the people less chatty. When Grainier runs into a fellow worker he knew years earlier, he realizes the old man has dementia. Their time and their shared memories are slowly being forgotten. Men die often. Boots nailed to a tree are all that’s left to mark the graves of those killed by rogue logs. After the burial, the work must go on.

When Grainier returns home from one of his work stints, the sky is black with smoke. Unable to find his wife and daughter in town, he ventures into the blazing trees. His cabin has been reduced to ash; nothing remains of his family.

Can such relentless change, such tragedy, be endured? As its title suggests, this is a tale of clashing worlds – of metal and smoke, reality and fantasy. Grainier experiences visions of his wife and imagines his daughter has survived and become a wild thing in the forest. He is haunted by the ghost of a Chinese laborer he failed to save from a lynching and fears he has been cursed. But life goes on. He rebuilds his cabin and stays there for the rest of his days.

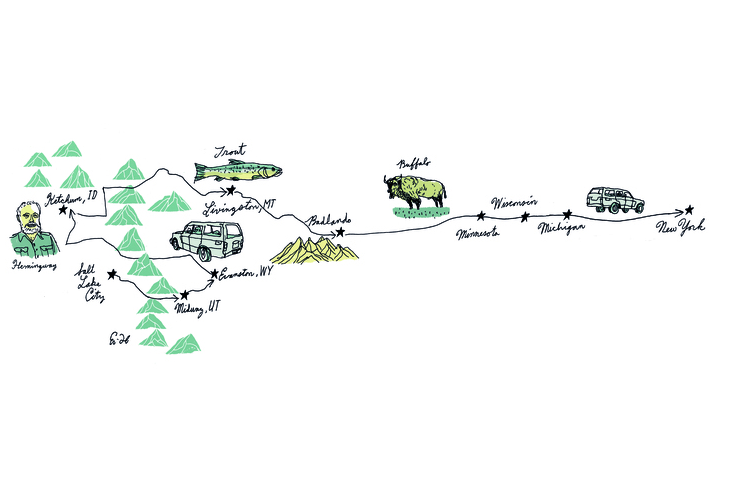

In the first few minutes of the film, actor Will Patton narrates, in sonorous voiceover, a passage from the novella that amounts to an obituary. Grainier “lived more than 80 years, well into the 1960s. In his time he’d traveled west to within a few dozen miles of the Pacific, though he’d never seen the ocean itself, and as far east as the town of Libby, 40 miles inside of Montana. He’d had one lover – his wife, Gladys – owned one acre of property, two horses, and a wagon… he had no idea who his parents might have been, and he left no heirs behind him.” The narration isn’t overbearing but lends the story of Grainier’s solitary life a sort of mythic quality.

Some things are inevitably lost in the transition from page to screen, things that only the written word can convey; some things are gained. Johnson’s prose is spare but interwoven with bursts of lyricism, much like emerging from a forest into a sunlit clearing. Bentley ups the ante with focused, Terrence Malick-esque shots of the lush green forest; the orange blaze of a campfire; the blushing sky at sunrise and sunset. Wood cracks and groans as trees are felled; birdsong fills the air. We are meant to linger here. “Beautiful, ain’t it?” asks old Arn Peeples (William H. Macy), an eccentric explosives expert, as he and Grainier share a moment of rest in the forest. “What is?” Grainier asks. “All of it,” Peeples says.

It’s a quiet sort of epiphany that coincides with death’s closeness: Peeples has been struck on the head by a widowmaker just moments before – and will die soon after.

Grainier’s own epiphany comes high in the air, as he experiences his first plane ride at a county fair for $4. Bentley fittingly chooses this significant passage from the novella to conclude his film: “The plane began to plummet like a hawk… he saw the moment with his wife and child as they drank Hood’s Sarsaparilla in their little cabin on a summer’s night, then another cabin he’d never remembered before, the places of his hidden childhood, a vast golden wheat field, heat shimmering above a road, arms encircling him, and a woman’s voice crooning, and all the mysteries of this life were answered.”

To adapt the old question: if a man lives a life in a forest, and no one is around to observe it, does it make a mark – an echo? Bentley depicts Grainier’s body being absorbed by moss, his cabin overgrown. And yet, we do not feel grieved for him. Grainier is forgotten. But for a moment, he was a life – someone who loved and mourned. He was there, and then he wasn’t. And that is all; that is everything.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 8, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply