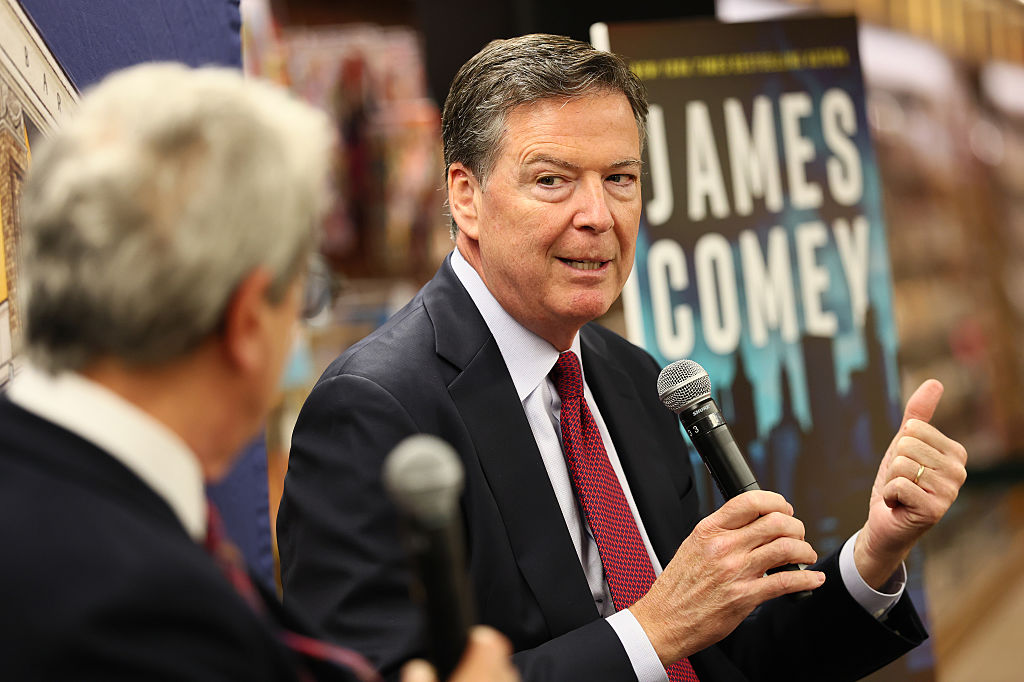

United States District Court Judge Cameron M. Currie, sitting by designation in the Eastern District of Virginia, yesterday dismissed the federal indictments against former FBI Director James B. Comey and New York attorney general Letitia James. At the crux of the court order is the judge’s finding that President Donald J. Trump’s administration unlawfully appointed Lindsey Halligan, the U.S. Attorney who signed the Comey and James indictments.

Taking the now familiar TDS cheap shot, the court order opens with a description of the U.S. Attorney as “a former White House aide with no prior prosecutorial experience.” Attorney General Pamela J. Bondi appointed Ms. Halligan as U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, one of the busiest jurisdictions in the country, on September 22, 2025. Three days later, Halligan secured a two-count indictment against Comey from a Virginia grand jury.

Comey challenged his indictment on October 20, 2025, asserting among other concerns that Halligan’s appointment was invalid.

Judge Currie dismissed both cases without prejudice, meaning the U.S. Department of Justice may re-file charges against Comey and James, at least theoretically. However, depending on which statement the Justice Department alleges forms the basis for its false statements and obstruction charges against Comey, the statute of limitations may have expired, preventing any further prosecution.

There is a genuine question over the violation of the separation of powers.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt announced the administration will appeal the dismissals by Judge Currie, a Clinton era appointee. It is by no means clear that Halligan’s appointment is unlawful or, even if it is, that dismissal of the indictment is the proper remedy.

First, the Judge’s order turns on an interpretation of the statute that denies the Justice Department more than one interim appointment in any U.S. Attorney’s Office. Nothing in the text of the statute prevents the Attorney General from making serial appointments. Additionally, prior administrations, including under Presidents Clinton and Bush, interpreted the law to allow “stacked” appointments, which went unchallenged. Also, the statute is phrased in the conditional, and it habitually uses the permissive verb of “may” rather than the strict command of “shall” or “must”.

Second, if the statute is interpreted to allow the Justice Department but one interim appointment, there is a genuine question over the violation of the separation of powers. Every case a U.S. Attorney files, whether criminal or civil, is ultimately tried or settled in the courtroom of a federal judge in her district. The idea that all the judges of the district who ultimately rule on the U.S. Attorney’s cases should also hand select the U.S. Attorney deprives the President of his authority over the executive branch, concentrates power in one branch of government in direct contraction of the Framers’ intent, and creates tremendous disincentives for prosecutorial independence.

Finally, the judge need not have dismissed any indictment signed by Halligan even if her appointment was lacking. The indictment was also signed by the foreperson of the grand jury, and it was the grand jury that possessed the actual authority to find that Comey violated federal law under a probable cause standard. Furthermore, the Justice Department may have a workaround to re-indict Comey under another relatively unused statute that essentially extends the statute of limitations by six months when a felony indictment is dismissed.

The judge’s dismissal of Comey’s indictment is just the beginning. Under the logic of Judge Currie’s order, any indictment signed by Halligan alone is presumptively invalid. It would be unsurprising to see defendants challenge even those indictments where Halligan was but one of multiple noted authorities. A wave of dismissal motions is coming from other defendants indicted this past fall in the Eastern District of Viriginia. Moreover, Judge Currie’s order has the potential for a tsunami effect as defendants across the country challenge their indictments in jurisdictions where other U.S. Attorneys are presiding who remain unconfirmed by the Senate.

Given the very high stakes that go well beyond the Comey case, the Trump administration has no choice but to appeal Judge Currie’s order. While the federal appellate courts sort out what the intersecting federal statutes mean for who actually runs the U.S. Attorney’s Offices nationwide, Congress should act immediately to untangle this imbroglio by amending the statutory framework for the President’s executive branch appointees. The President must possess the authority to appoint members of his own administration. Whatever role the Congress should have for advice and consent may vary from position to position, as is clear under the plain words of the Constitution itself, but in no event should the courts be appointing employees of other branches of government. The issue must be settled, not simply for President Trump’s team, but for every administration to follow.

Leave a Reply