Everybody is suddenly recognizing, almost in unison, that many major of the cultural shifts in recent years were accelerated, if not explicitly caused, by Covid lockdowns. In confinement we went online and when we spent more time in cyberspace than in meatspace, our brains began to change.

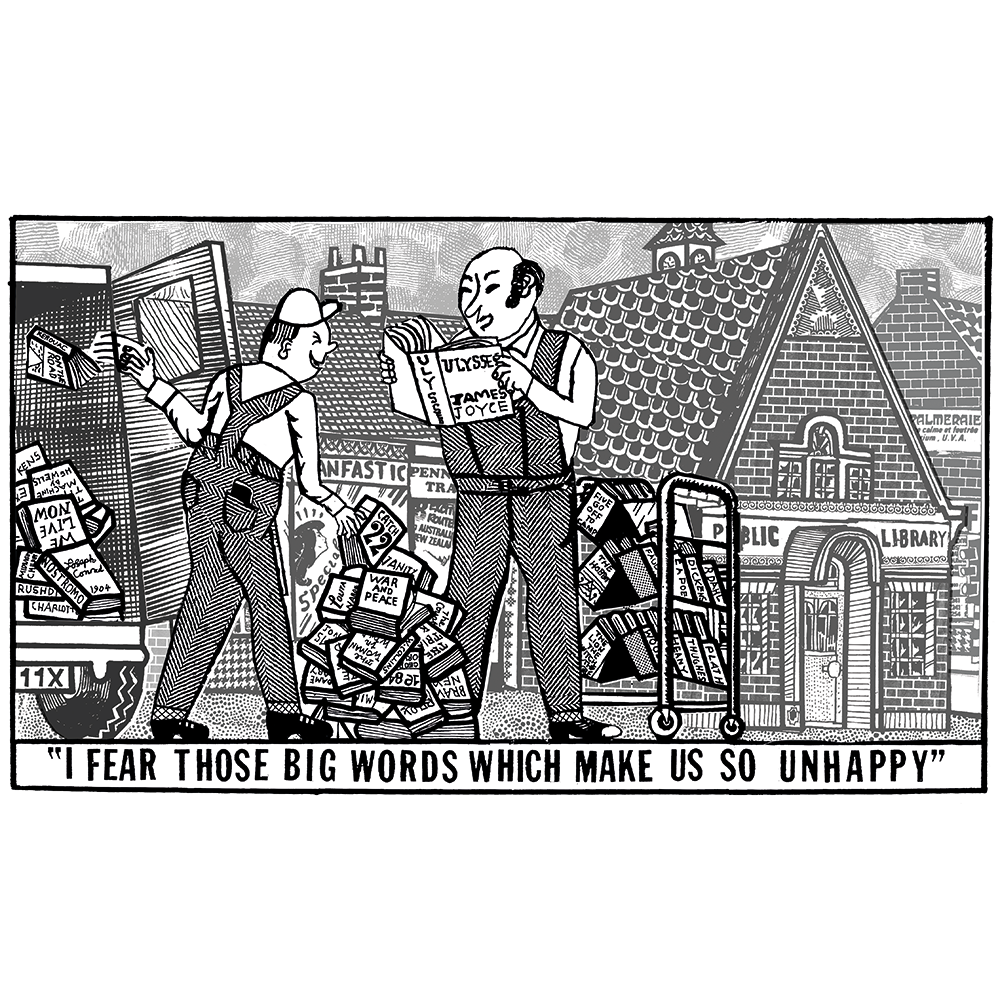

The most significant shift is that we have turned away from books and reading, and as a result our attention spans are collapsing. The screen is eclipsing the page. In the US, reading for pleasure has crumbled; in Britain, a third of adults no longer read books at all. The “reading revolution” that expanded consciousness in the 18th century is in retreat. But what’s emerging is not illiteracy: it’s post-literacy. We are becoming post-literate.

Daniel Kolitz’s extraordinary Harper’s Magazine piece on the hyperonline masturbatory “gooner” subculture captures this shift, as do phenomena such as TikTok and its seeming monopoly over trend creation, the growing visibility of networks such as 764, the tide of “slop violence” and the ubiquity of what etymologist Adam Aleksic calls “algospeak.”

One aspect of this transformation remains underexamined, though: the rise of voice. Voice memos, podcasts, audiobooks.

I now listen to most news articles and have had to bribe myself to start actually reading them again. Our machines have also started to talk back – first Alexa and Siri, now ChatGPT. We are consuming more sound and thinking out loud. These circumstances explain the rise of “crying in your car” videos: a need to hear yourself speak to understand what you’re feeling. It’s also why there seem to be more information leaks: people are simply not thinking about what they post or share online because voice culture has collapsed their impulse control.

Voice culture destroys the distance between impulse and articulation, thought and expression; between what is felt and what is said. It is perfect for an age that values presence over patience. When we talk to a device, or listen to someone talk into one, we bypass the delay that literacy once demanded. That pause once served as a kind of psychic buffer, a silent interval where imagination and internal modeling could take shape. Writing required withdrawal, a temporary step back from the environment in order to structure experience in words. Its disappearance signals something deeper: the erosion of interiority itself.

The journalist and media theorist Andrey Mir has a name for this shift. He calls it “digital orality,” a return to old oral patterns of thought, but now mediated through digital technology. I spoke to him recently about the sort of humans we’re becoming. He explained that in many ways, what we’re seeing is a return to the past.

“Before writing, humans were immersed in a physical [nature] and social [tribe] environment,” he said. “They received information from their surroundings simultaneously, in what Marshall McLuhan called ‘acoustic space.’ Writing and reading detached humans from the environment and forced them to immerse themselves in the contemplation of ideas and thoughts.”

Mir believes that the inner vision literacy created enabled major cognitive transformations, the first being what he calls a “long focus” on ideas. “If you live in nature and concentrate for too long on your own ideas while detaching from the environment, someone or something can eat you,” he says. “An oral/tribal person has to be immersed in surroundings, not ideas. Writing and reading enabled a delay of reaction, which was used for contemplation. This led to deliberation, which, again, is not typical of ‘natural’ environmental immersion, when individuals react fast, impulsive.”

Reading trained us to think in sequence – to slow down and structure our thoughts. In the absence of reading, this skill is fading. As Mir says: “Writing, just technically, requires a linear organization of content. You need to write any content word after word, sentence after sentence, idea after idea – one thing at a time. The linear nature of writing structured not only writing itself but also thinking and, eventually, the world. The literate mind and the world perceived by it are structured because of the mere technicality of writing.”

The cognitive “inward turn,” enabled by writing, led to theorizing, classification, individualism, self-reflection, the structuring of knowledge and rationalism. So what will the collapse of writing and reading lead to? Mir and I agree that without reading we lose logical thought and impulse control, but we disagree about how important voice culture will be to the future. Mir insists that voice isn’t the point, that I’m focusing on the wrong thing. Digital orality, he argues, happens primarily through text and will continue to. The cognitive shift toward impulsivity and environmental immersion doesn’t necessarily require speaking.

“Text in email, and especially on social media, is similar to talking – it is conversational, impulsive and immersive. I believe texting will hold a strong position in users’ habits of communicating with each other and smart devices or AI – at least until mind upload happens, when no mediation, text or speech will be needed at all,” he says.

“But until then, texting will remain the dominant medium of digital orality. The reason is simple: the physical isolation of digital users, especially digital natives. Due to the comfort and intimacy of personal devices, they are conditioned to maintain strict physical and social boundaries, hence the growing social anxiety of younger generations. They will not ask AI in public – they will text it. It’s more intimate and comfortable, but no less important: texted conversation is storable and shareable. It’s convenient to share or refer to and it allows embedding visuals – emojis, GIFs, reels, memes, et cetera. This is a very important part of digital conversation and self-expression. That’s why voice interfaces, while convenient in certain circumstances, will not replace texting.”

Something new is certainly emerging, but I disagree with Mir. I think the post-literate man will discard written words entirely. Take the rise of short-form video. You can’t multitask while watching it – not really. It demands your eyes, your attention, your full sensory involvement in a way that texting just does not, however immersive and conversational your texts. TikTok doesn’t allow the same fragmented attention that refreshing Twitter or firing off messages does. Audio and visual information delivered rapidly and seamlessly creates a different cognitive state than tapping out texts.

When you speak to ChatGPT or Siri or Alexa, you’re not just inputting information differently – you’re thinking differently. The delay between thought and expression vanishes entirely. This isn’t like texting, which still preserves a moment of formulation, however brief. Speaking to machines trains us to externalize cognition itself, to treat articulation and thought as simultaneous rather than sequential. Thought no longer requires even the minimal internal processing that typing demands. It bypasses interiority altogether, flowing directly from impulse to expression to environment.

I ask Mir how much audio-driven content – podcasts, audiobooks and voice memos – will reshape journalism and storytelling. He says: “I think podcasts and audiobooks have displaced much of talk radio and news radio already for drivers. Radio, one of the last old media comparatively unaffected by the internet, survived precisely because drivers couldn’t use their hands or eyes while driving, thus protecting radio consumption from touchscreens.

“As soon as self-driving cars free drivers’ hands and eyes, radio share will shrink and take its place somewhere near newspapers among endangered species. This is already happening. However, some activities require hands and eyes but leave ears free for parallel media consumption. Radio will share this niche with podcasts and audiobooks. Anyone producing audio content should remember it is a secondary, background medium.”

What skills or “literacies” might be necessary for people to effectively navigate our changing media ecosystem?

“Literacy structured the world in the pattern of a catalog. Education was essentially the study of the catalog of knowledge to enable access to any other, more specialized knowledge,” Mir says. “The first websites were organized like books or libraries – with tables of contents or catalogs. The search box killed the catalog. With the search box, knowledge acquisition shifted from theorizing and reading to asking and talking. Consequently, the crucial skill in this mode of operation is prompt literacy – what to ask to get the best answer. Moreover, prompt-literacy will soon become a matter of safety when we start prompting smart cars, smart homes and anything smart with the capacity for physical action. With the wrong prompt, a smart device can hurt you socially or physically. Another crucial media skill is not learning how to use a medium, but learning how not to use it.”

According to Mir, “Media evolution uses our hormonal stimuli for finding, sharing, socializing, thus fostering dopamine addiction to media use. This way media evolution makes us work for it. Just as bees are sex organs to plants, we are the sex organs of the media world. We help the species of media evolve. They reward us with convenience and hormonal satisfaction. Understanding the hormonal nature of media consumption is crucial for media literacy, as it may help us switch off a device or switch between devices. Ultimately, media literacy is time management, and the time in question is the time of your life.”

Mir’s work is vital and brilliant, but my view is that we have passed the point of being able not to use technology. We’re beyond even digital orality, entering something post-human: a state where the boundaries between thinking, speaking and acting grow increasingly porous. Where machines talk back. Where we think out loud because we can no longer think in silence. Where voice replaces text as the primary medium of existence.

Mir has a different take. He thinks that the generations that knew a time before smartphones – the digital “migrants” as opposed to the “natives” – must push back to ensure that future generations have a chance to become “media literate.”

“We, digital migrants, lived in times without personal digital devices, so we have experience with alternative communication. We still think digital use is a choice. It is not the case for a person who has consumed touchscreens since toddler age,” Mir says. “Digital natives are conditioned by touchscreens and digital orality, as it’s the only mode of mediation of the world they know. Parents bribe babies with tablets to buy some child-free time; kids go to video games with conversational interfaces, then social media. This all fosters a completely different cognitive type in younger generations.

“Pre-digital people generally know that significant effort brings significant and multilayered rewards. Reading Dostoyevsky requires significant effort but brings not just intellectual epiphany but also social status and self-actualization. Building a romantic relationship requires long efforts but brings not just sex, but the comfort of marriage and the security of family. The sizable reward requires a sizable effort – this was the essence of the effort-reward system in the physical world.”

But there are rewards in the online world, I say. Mir says: “Digital devices reward mere clicks, but the reward is also subtle. It never satisfies – it just keeps the user using the device. This radically rewires the effort-reward neurophysiological circuits. Digital media reward mere presence – just click to show yourself, your preferences – and therefore, mere presence, not effort, becomes something valuable. On digital platforms, ‘to do’ is not as important as in the physical world; what matters is ‘to be’ – to indicate your presence.

“This cognitive setting leads to tectonic cultural consequences. The prevalence of ‘to be’ over ‘to do’ leads to the snowflake generation and identity politics, where identity trumps merit. It’s not important what you do; it’s important what you are – and so people see identity as credentials and demand rewards or penalties based on identities, not deeds. Another outcome of the digital media shift is the fading ability of individuals to make long-term efforts. The brain is not conditioned to work hard and long when the effort worthy of reward is a mere click away. As a result, education degrades, careers become harder to pursue, personal lives become difficult to build, etc. Overall, social anxiety grows.”

So what can we do to best deal with this shift to digital orality?

“Dealing with this issue starts with parenting. As a general rule, kids’ access to types of media should repeat the stages of humankind’s media evolution – physical toys and active games, listening to bards (parents), reading, electronic media, and only then, sometime around the age of 14, touchscreen devices. If the order is broken and digital devices come before toys and books, the brain won’t receive the neural exercise associated with previous media – eye-hand coordination, physical space orientation, concentration, diligence, long effort and delayed reward.

“However,” Mir concludes, “the world has already switched from print media to digital devices and we live inside the shift from print literacy to digital orality. No personal strategy can cancel or reverse this shift. We need to get used to it.”

Katherine Dee will be writing a regular technology column for The Spectator. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply