Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, discussion of the Ukrainian far right has been verboten in western media, largely because one of Vladimir Putin’s stated war aims is the “denazification” of Ukraine. Putin’s claim that Ukraine is a Nazi state has been recycled by Russian propagandists and the western party line has consistently been that while the Ukrainian military does have far-right strains, they are marginal and inconsequential. This may have been true in 2022, but things have changed significantly after almost four years of war. Today, far-right figures control some of Ukraine’s strongest military units, and neo-Nazi ideology is displayed openly in the Ukrainian ranks.

The latest evidence of this came on November 4, when Volodymyr Zelensky handed out military awards to soldiers fending off the Russian offensive in the Donetsk region. As shown in photos published on Zelensky’s official Telegram and X accounts, some of the soldiers receiving the awards had patches with symbols that looked suspiciously like the emblem of Hitler’s SS. The unit flags adorning the walls told a similar story: the Azov brigade’s insignia is a variation of the Nazi Wolfsangel, while the Chervona Kalyna brigade’s ensign emulates the red-and-black flag of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, a far-right militia that played an instrumental role in the Holocaust in western Ukraine and massacred tens of thousands of Poles in the regions of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia between 1943 and 1945. Zelensky was photographed with these two flags in the background.

Both the Azov and the Chervona Kalyna brigades form part of Ukraine’s 1st Azov corps, a unit that comprises tens of thousands. The corps is led by Denys Prokopenko, the commander of the Azov regiment that defended Mariupol in 2022 before being captured by the Russians. He and his men were eventually freed from captivity in a prisoner exchange and their “heroic resistance” was praised by the western media. What was often left out of the gushing puff pieces was Prokopenko’s background. In the 2010s, Prokopenko was a member of a far-right Ukrainian soccer-hooligan association called the “White Boys Club.” A quick browse through its Facebook page shows frequent glorification of Nazi units such as the 14th Waffen Division of the SS (also known as the 1st Galician division). In 2014, Prokopenko joined the nascent Azov. His platoon was nicknamed “Borodash” (bearded man) for its insignia, which featured a bearded Nazi Totenkopf. In spite of appearing to like the aesthetics, Prokopenko has denied that he or the men serving under him have far-right sympathies.

But the 3rd Army Corps, comprising some 40,000 men and widely heralded as Ukraine’s strongest military formation, is commanded by an even more sinister figure, Brigadier General Andriy Biletsky. In 2010, Biletsky publicly stated that Ukraine must “lead the white nations of the world in a final crusade for their survival, a crusade against the Semite-led Untermenschen.” In 2014, after being held as a political prisoner, he founded the Azov volunteer battalion to fight the Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas. From 2014 to 2022, human-rights organizations described widespread use of torture by Azov fighters against civilians in the Donbas and western media routinely reported on how this white-supremacist, fascist and neo-Nazi paramilitary unit served as a model for violent far-right extremists all over the world. In 2016, Biletsky also established the far-right political party National Corps, which the US State Department called a “nationalist hate group” in 2018.

In those days, contrary to Russian propaganda, the Ukrainian people had little affinity for the extremist ideology of Biletsky and the Azov movement. Although Biletsky managed to get himself elected to the Ukrainian parliament, his party only received 2 percent of the vote in the 2019 elections. In other words, prior to the war, Azov was a fringe phenomenon.

That changed in 2022. After the Azov’s capture and release by the Russians, figures such as Prokopenko and Biletsky became national and international heroes overnight. From a regiment in 2022, Azov grew to a brigade in 2023 and a full corps this year. Today, its members are among the most admired men in the country.

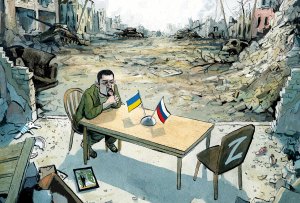

There’s a reason Zelensky is so resistant to signing an armistice, especially one involving territorial losses. In promoting such men as Prokopenko and Biletsky, the President has potentially created a monster. If their ideologies are as suspected, Ukraine is now in the position of Germany in 1918. Fighting a war of attrition against an opponent with vastly more resources, manpower and firepower, Ukraine is bound to lose, or at the very least to suffer major losses. After World War One, the Dolchstoßlegende – the stab-in-the-back myth – spread around Germany. It convinced many Germans that the country hadn’t lost the war on the battlefield but had instead been betrayed by citizens on the home front – Jews, mainly. After years of Ukrainian and western media hyping up the Ukrainian army and predicting a Russian collapse, an unfavorable peace risks creating Ukraine’s own version of the Dolchstoßlegende, with Zelensky playing the role of the Jewish scapegoat.

If a ceasefire is signed, it is far from clear whether Prokopenko and Biletsky, who believe in victory at any cost, will lay down their arms. Between them, they command tens of thousands of Ukraine’s best troops. Well-equipped, well-trained and ideologically motivated, these units have the potential to be Ukraine’s very own Freikorps, and Prokopenko and Biletsky may well lead their own Kapp Putsch or march on Kyiv in the event of an American-mediated diktat.

While some armies have neo-Nazis, in Ukraine some neo-Nazis have armies. The threat they pose to a democratic and prosperous postwar Ukraine is obvious.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply