An adage dating at least from my adolescence: “You either use it or lose it.” This bit of folk wisdom, which refers principally – or so I understand – to the male procreative organ, has always been considered so obvious as to hardly need stating. Thus the recent discovery that the same principle goes for another human organ – the brain – should not surprise anyone.

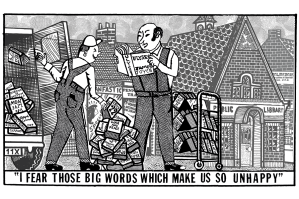

The fields of science and pedagogy are agreed, for now at least, that humans who shut down their minds, temporarily but with increasing frequency, and substitute artificial intelligence for them, end by weakening their mental capabilities in the areas of cognition, memory and attention span; put more bluntly, they make themselves progressively stupider by a physical and psychic process that the least intellectual of what used to be called “jocks” would have had no difficulty understanding, owing to their own regimen of physical training and endurance.

Nevertheless, it is a finding that the digital geniuses of Silicon Valley apparently failed to anticipate; or perhaps they did so decades ago but pressed ahead in the expectation that the dumber the human race, the more money it would be eager to shell out for their magical mental crutches as an evolutionary replacement for its primitive cerebellum, cerebrum and brain stem.

Cynical of them, of course, but entirely logical and far-seeing; prophetical, even. Virtually every invention since the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution has been what came eventually to be called a labor-saving device. The steam locomotive made travel over distance infinitely more comfortable and less demanding than travel by coach and horses. The automobile did the same for travel by horseback. Machinery replaced factory laborers with machine operators. Household gadgetry freed housewives from most physical labor save that of pushing buttons, while leaving them the lion’s part of the day to watch soap operas, go shopping, gossip and have clandestine affairs with the postman.

It remained only for that most strenuous and unpleasant type of labor, deeply resented by all but the most minuscule portion of humanity – that of the mental kind, also known as thinking – to be made redundant. Now, with the advent of AI, this final Everest standing in the way of the fullest realization of human bliss is, it appears, about to be summited and the flag representing the ultimate stage of industrial and scientific progress planted and unfurled to wave on the alpine winds. Its emblem will depict a fly on a can of garbage on a background of bilious yellow.

Marx knew what he was about two centuries ago when he defined “workers” as physical laborers, thus intimating that all who make their living by intellectual occupations are society’s drones, members of a pan-cultural Drones’ Club established to exploit the heroic, self-sacrificing “working classes” dedicated to performing civilization’s most strenuous, exhausting and unpleasant tasks. For Marxists, physical labor is by far the most noble type of work, highly deserving of grateful recognition in terms of status and financial reward by the rest of society. (I knew a fellow student at Columbia who argued that a subway driver should make more money than a medical doctor or corporate executive, his job being presumably less pleasant than theirs, though tastes vary of course.)

The truth is that the opposite is really the case. Compared with the intellectual classes, the laboring masses, who, being unacquainted with the rigors of mental, professional and artistic engagement – that of the mind and of the imagination – do not know what truly arduous work is. The heroic worker rises early in the morning, punches the clock when he gets to the work site, and again when he leaves it, having put in exactly the hours his boss – and his union – specify. He goes from the workplace straight to home, or to his bar, or to his sport, never gets a call from the boss after hours, and needs never give his job a thought until the alarm clock sounds again in the morning. The mental requirements of his job are, typically, nil compared with those imposed by the learned professions, and even by business.

Granted, a substantial proportion of so-called intellectual work today – in the colleges and universities, in the media, in “entertainment,” and even in the so-called arts – is simply counterfeit work: vacuous, silly, irresponsible and often immoral, requiring little if any talent, effort, or real intelligence to accomplish. Compared to it, the honest labor of an electrician, a carpenter, a commercial fisherman, a cowhand, a roughneck (I know – I’ve worked in the oilpatch), or a lumberjack has a plain and simple heroism about it, in particular where it involves the physical skill and danger that artificial intelligence can never replace.

Still, the fact remains that for the vast majority of people, manual work is preferable to (being mentally less painful than) work of the intellectual sort, without which the great and complex systems of human imagination, invention and organization that create and perpetuate the jobs that the laboring class depends upon would not exist.

Artificial intelligence need not affect the blue-collar workforce much, if at all, save to the extent that it replaces human brawn and physical skill with computers and ChatGPT. But it could have devastating consequences for the educated – the so-called intellectual – class by encouraging it to atrophy its oh-so-superior brains by relying on AI to do its work for it; work that only the human brains that created it can, in the final analysis, intelligently do. Intelligence is the engine that has always made the world go round, and always will be – human intelligence, that is, not its artificial substitute.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply