Around midway through Masquerade – the new immersive adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera, which sees a small audience whirled through a labyrinth of rooms and sets – I feel a hand on my shoulder. Smiling, I turn, expecting to see my friend – and immediately recoil.

A tiny circus freak grins at me, revealing teeth like sharpened screwdrivers and a painted face lifted straight from Día de los Muertos. Later, in a carnival scene, that same freak hammers three nails into her face and an ice-pick up her nose.

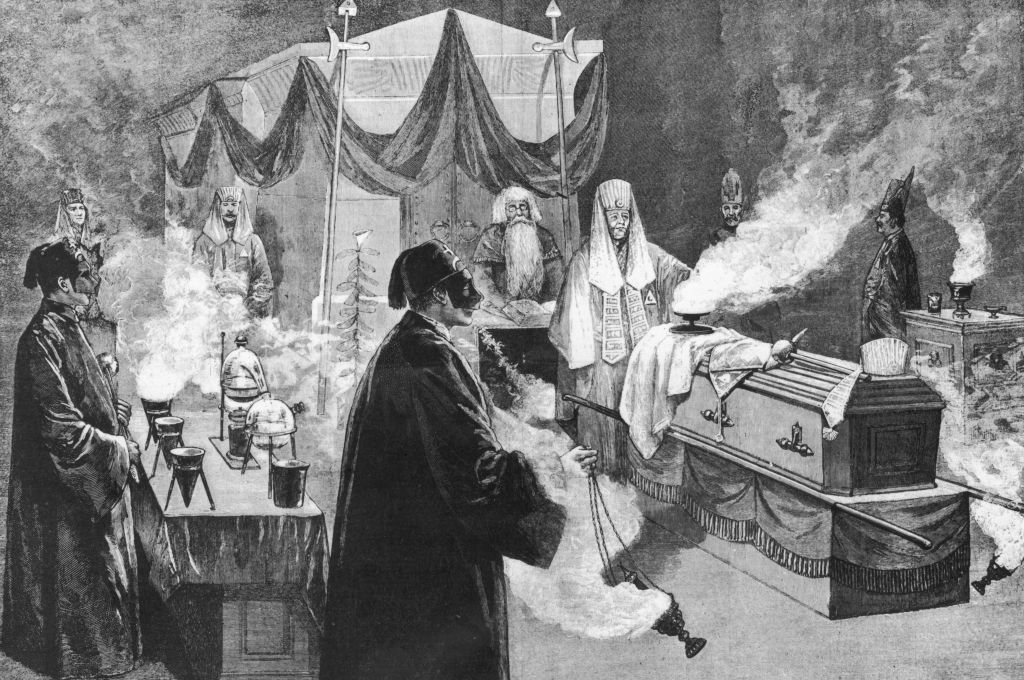

The carnival sequence is not in the original Phantom. It is one of the largest and perhaps most important of Masquerade’s additions. In it, we see the Phantom’s origin story: a young, malformed man is locked in a cage; a burlap sack is tied over his head, to be gawked at by paying customers. He is rendered literally faceless.

When his keeper lets him out to remove the sack and do the big “reveal” to the crowds, he escapes. We follow him, scrabbling away from his weeping owner (“he was like a son to me!”), to the Paris Opera. There, he hides away in the bowels of the building – a loner, until he becomes infatuated with the chorus girl Christine.

The episode elicits sympathy and explains the Phantom’s destructive behavior. He is, after all, a killer, stalker and kidnapper. Most importantly, it makes Masquerade squarely the Phantom’s show: he is misunderstood, rather than evil.

The Phantom of the Opera closed on Broadway in 2023 after a 35-year run. Diane Paulus, creator and director of Masquerade, attempts to fill the void with a giant exercise in fan-fiction that cleverly submerges the audience into the story – sometimes as flies on the wall, sometimes as actual players. It’s fabulous, fun and fantastically extravagant.

Set across six stories of an empty19th-century building in New York City, the experience is spiritually akin to Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, but rather than being a “choose your own adventure,” the plot is already laid out, and the audience – who are also masked and must wear black, silver or white formal attire – is tightly guided from room to room.

Everything is done on a grand scale: we dash up and down escalators, in and out of rooms, past artworks and scenery that we barely have time to take in. But, despite its sheer scope and magnitude, Masquerade succeeds because it feels so intimate. We’re here with Christine as she prepares for a performance in her small, cramped dressing room. We can reach out to touch the Phantom in his cage. We are underneath the chandelier before it crashes to the floor. “I’m glad you made it!” one of the side characters tells me, his hand fleetingly on my shoulder and his eyes locked on mine for just a second before he runs past.

Nowhere is this intimacy more apparent, though, then when it comes to the theme of lust. Our Christine, the young innocent who attracts the destructive forces of the night, is both intellectually and socially revolted by her suitor even as she finds herself irresistibly drawn to him and sexually awakened by his presence.

Paulus turns up these motifs of repressed desires to the max – not least in a scene where we creep up on Christine in bed. As she sleeps in a virginal, white – and very wispy – nightgown, the Phantom’s hand appears from behind to caress her. She arches her back and parts her lips. It’s embarrassingly sensual, casting us as the voyeurs. The Phantom may be ugly compared to Christine’s handsome but bland suitor, Raoul. But the Phantom offers her sex, danger and a voice.

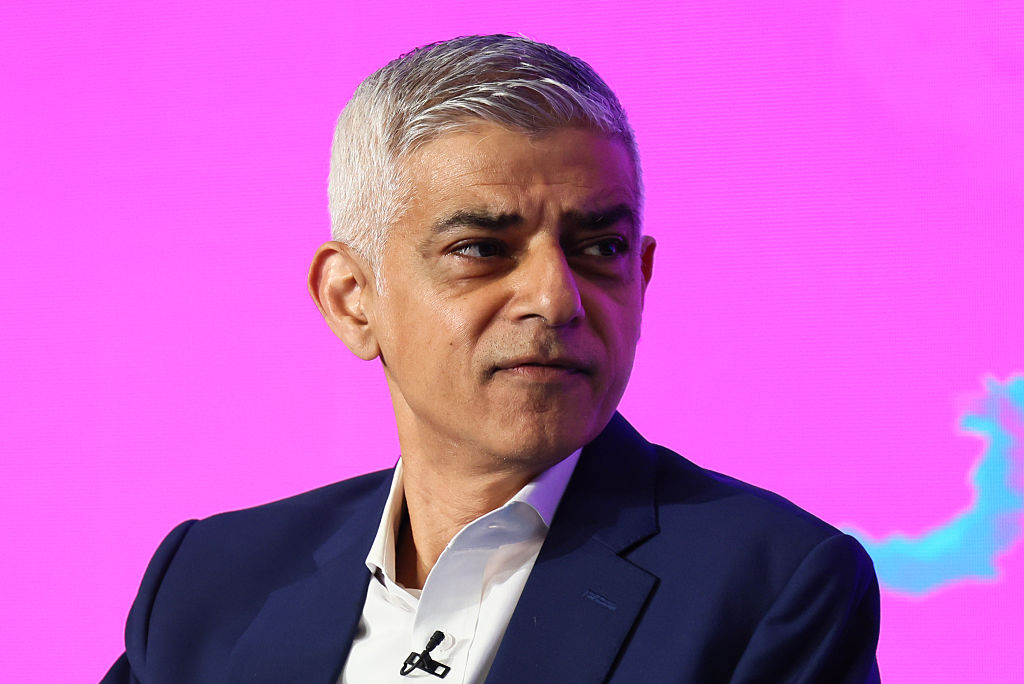

Song, of course, matters in a musical and although the instrumentals in Masquerade are prerecorded (there’s no space for an orchestra on the move), the cast’s voices are big and their performances heartfelt, if at times mawkishly sentimental. When I visited, the very youthful and very talented Anna Zavelson played Christine as beguilingly naive and wide-eyed, opposite the always-convincing and often-debonair Jeff Kready as the Phantom.

It was only when we were spat out into an ornate gothic-styled cocktail bar at the end of the show that I saw the hundreds of other people who had attended the same night as me – and realized they had been in the building with us the whole time. (“Where did they all come from?” my companion asked).

In fact, audiences of 60 people at a time enter the building 15 minutes apart, with six Phantoms and Christines, and three Raouls, performing for six separate groups (many of the other actors rotate their roles between all six performances). That we never overlap, even during moments of transition, is extraordinary.

And yet the most moving scenes for me came when we shed the elaborate sets and climbed outside into the chilly fall air on the building’s roof. There, among the skyscrapers and office buildings of Manhattan, we hear Christine and Raoul sing a love song to each other. Later, Christine aches for her dead father as a lone violinist disappears into a mausoleum in the sky. It is a moment that asks us to use our imaginations and to lean in – to the romance, to the melodrama, to the grief, to the histrionics and, yes, to the silliness. In a maximalist show, full of pizazz and ambition, we could finally take a breath.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply