Todd Goddard opens his biography of Jim Harrison, the first since the poet’s death in 2016, with an account of a 37-course meal Harrison once consumed in France, over the course of 11 hours. Harrison composed a comic recital of the event, “A Really Big Lunch” for the New Yorker. He loved gourmet dining to the point of gout and revered alcohol as well, guzzling potent vintages in quantity.

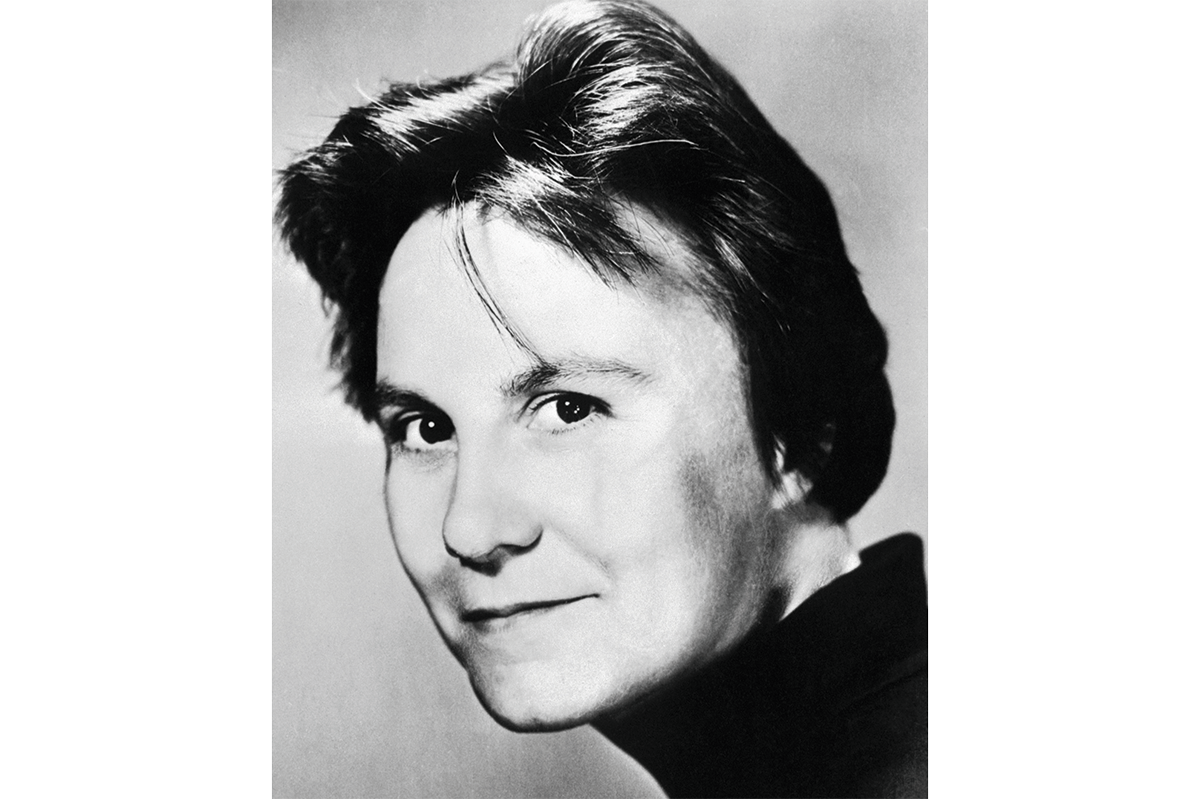

“Eat the world” was the phrase Harrison lived by, Goddard tells us, which alludes to an appetite for all existence. The cumulative effect of such global consumption is evident on the cover of Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, a Writer’s Life. Its close-up of the grizzled Harrison resembles those wry Renaissance portraits in which the facial features are made up of fruits, vegetables, fish, even books.

Harrison set out to be a poet, nothing more, but went on to write novels, essays and screenplays also. Quitting a college teaching job after two years, he determined to follow the dictum of that other deep drinker, William Faulkner: that a writer is responsible only to his art. What ensued was a vividly adventurous life. He took off on impromptu cross-country road trips that invite comparison with Jack Kerouac’s. But where Kerouac would slouch off to some hipster city, Harrison, soon enough, found greater inspiration in forests and mountains, plains and their peoples; he knew farmers and farming, and drew near to Native Americans, their lives and tragic losses. He said to a friend, of his novel The Road Home, that in writing it he sought “the soul history of our country.” Many felt he found it.

In northern Michigan, Goddard goes so far as to search for an ancient pine stump where Harrison sat to watch wildlife, sometimes crawling into its hollow to escape rain and snow. Harrison wrote so prolifically of his experiences that it might seem a biographer would find it hard to enlarge his story. But there were windrows of his papers and letters and most of his close friends were extant, perhaps having lived with less hazard to their health. Harrison died at 78, his heart done, while writing a last poem in Montana. Goddard’s chronicle of the life is enthralling and adds much new and striking material, not only on Harrison’s already known life but also on the sacrifices made by his family, including the fact that as a teenager, one of his daughters had to take a job to pay the monthly utility bills. Goddard does not, however, find the stump.

Of Harrison’s heterogeneous work the only possible summary is numerical. He published 16 books of poems, 12 novels, some 25 novellas, four essay collections, a memoir and a children’s book. He wrote hard, sometimes retracing his narrative tracks, discovering fresh scent. He revived the novella, a neglected literary form that fit his marbling of action and introspection. Yet always he felt he was foremost a poet, writing in open forms that reflected his thought and un-thought. A Harrison poem comes alive like a one-eyed raven, watching you as you read it.

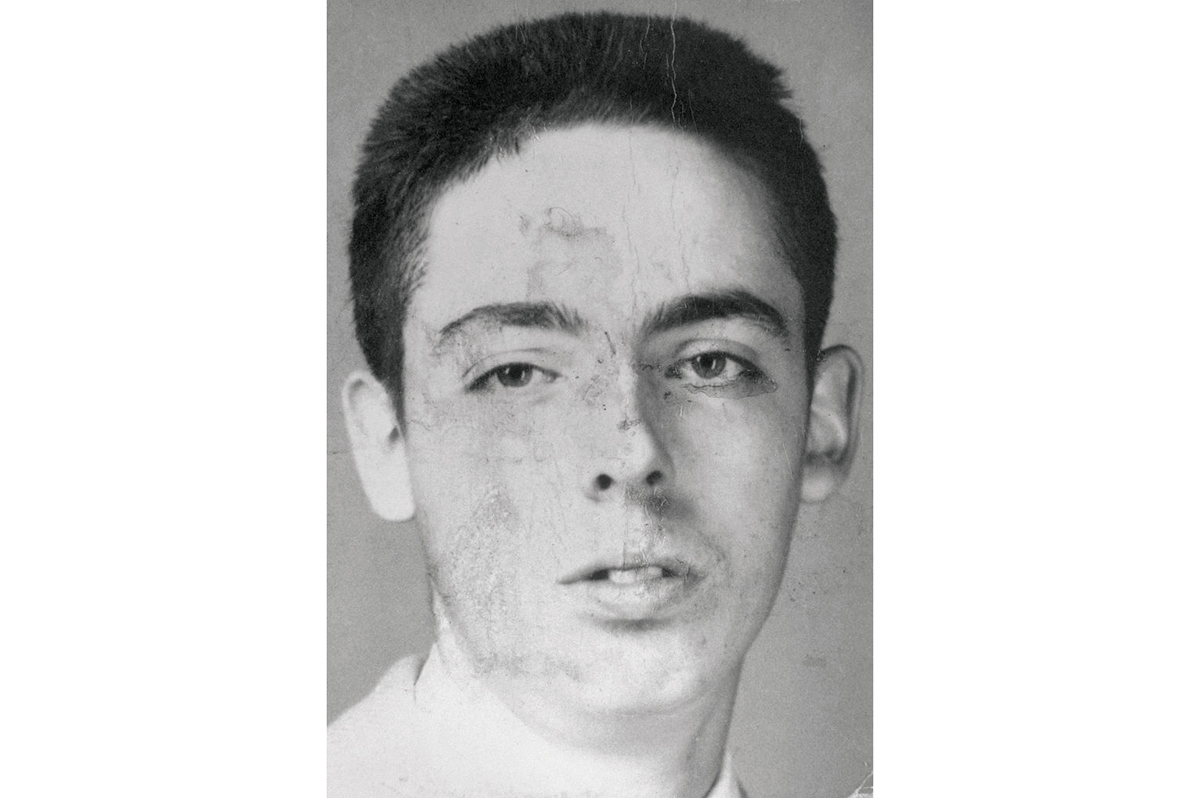

Harrison was born on December 11, 1937 in Grayling, Michigan, to parents of Swedish descent. His father was a state agricultural agent and his grandparents farmed, so he found out where his food came from early in life. Both parents were readers and their home brimmed with books. At seven he suffered grim trauma when a playmate struck him with a bottle and he lost the sight in his left eye. Harrison’s father had a cabin on a lake, so he began to wander in the woods and learned to catch bass.

Much later he made his way, off and on, through Michigan State University. He hitchhiked to New York and Boston, where he inhabited ratholed flats and worked at becoming a poet, also toiling as a waiter and a bookstore clerk. He met Jack Kerouac. Magazines decided to pass on the poems he mailed them. Returning to Michigan, he married Linda King, whose parents had been unable to fend off the penniless self-proclaimed poet. A daughter was born, named Jamie.

Trauma struck again. Heading off on a hunting trip, Harrison’s father and sister were hit by a drunk driver and killed. Though they had asked him to come along, he had delayed in declining and felt guilty for the timing of the accident. If they’d left a minute sooner, they’d have lived. He loved them both deeply. In the aftermath, his depression, in itself nothing new, worsened. Money was a worry: his manual labor didn’t help much and his poems got no recognition.

Through the providential efforts of the poet Denise Levertov, who had seen and admired his work, his first collection of poems was published, a book titled Plain Song (1965). This was remarkable for someone whose few verses had never made it into a magazine. It won him a faculty post at the State University of New York at Stony Brook the same year, where, besides teaching, he would set up a poets’ conference that devolved, in his own words, into “an unspeakable drunken atrocity.”

Two years in the academy were all he could take so he moved back to Michigan with his family, as always. He had the fortune, bad or good, to fall off a high bank when bird hunting and land himself in hospital for several weeks. His friend Thomas McGuane, whose novel The Sporting Club (1968) had come out successfully, urged him, while lying in bed, to write a novel of his own. He did – but for a work of fiction, Wolf: A False Memoir (1971) stuck pretty close to the facts. A young man, just angry enough for a novel of the 1970s, roams the Northwoods searching for a possibly numinous wolf, with flashbacks to his days of subsisting, barely, in soul-killing big cities. It works – one imagines it being narrated in the timbre of Robert Mitchum. The theme, Harrison would later assert, was “freedom, the compulsion to be free and to work it out for one’s self.”

For the money, he wrote superb magazine pieces on fishing and other outdoor sport. In a dark November he departed for Russia on assignment to cover the “suppressed” sport of horse racing there. It proved impossible to view the races, but he became intrigued by the Russian poet Sergei Yesenin, who wrote lyrically of rural life and hanged himself in 1925. Harrison, who had suicidal thoughts of his own, wrote a book-length sequence of prose poems, Letters to Yesenin (1973), which seemed to be prayers to a poetic savior. Indeed “Yesenin” was not so far from “Yeshua,” the Hebrew form of Jesus. In one poem he backs away from his darkest thoughts upon seeing the red robe of Anna, his second daughter, hanging from a door.

Harrison had done some itinerant preaching in his teens, thinking he might have a religious vocation. Later he leaned into Zen (as in the long poem “After Ikkyu”) and the Native American reverence for Earth, yet still believed in the Resurrection. He decried the “Calvinist work ethic” but celebrated it in Sundog (1984), a novel about a foreman on a Third World dam-building project. Goddard suggests it was work, dogged writing, that carried Harrison through his depressions. That, and the long-sought recognition that resulted – and money, mostly from the movies.

The film made from his early novella Legends of the Fall (1994) starred Brad Pitt and Anthony Hopkins. It was a box-office success. Harrison also co-wrote Wolf (1994), starring Jack Nicholson in a tale of lycanthropy, which bore no real connection to Harrison’s novel. But it dragged him into a showbiz whirl: he was hanging out with John and Anjelica Huston, Neil Simon, Orson Welles and Jeanne Moreau, and having an affair, briefly, with Jessica Lange.

It’s a long way from sleeping on the prairie with a calf nuzzling him in the night. He did that in the run-up to writing Dalva (1988), one of the later, longer novels which, along with his poetry, may be his highest achievement. Parts of Dalva unfold on the grasslands of Nebraska, a backdrop as dramatic as any on Earth, as the title character sets out to find the son she was forced to give up long ago, whom she bore by a half-Sioux man killed by his own hand in the wake of the Vietnam War. The novel is less personal and more panoramic than Wolf, as is True North (2004), a tale of violent atonement for the sin of scalping the virgin forests, where later a writer would sit on a stump.

In his final published novella, The Ancient Minstrel (2016), Harrison had his poet-hero define writing as “showing off for pay.” His own struggles and visionary oeuvre reveal the writer’s life as something far more serious and sacrificial than that – and much more mysterious. Goddard has given us the narrative that Harrison, with all his gifts, would not have written himself, guiding us to the wellspring, spiritual and romantic, of all his sparkling works. Dip in and drink the world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply