Everyone can name JFK and his (probable) assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, or Abraham Lincoln and everyone’s least favorite actor, John Wilkes Booth. But what of James A. Garfield, America’s short-lived (in both senses) 20th President, and his murderer, Charles Guiteau? Both men have disappeared into obscurity, at least until Candice Millard’s award-winning 2011 true-crime history Destiny of the Republic, which skillfully unpicked the sheer strangeness of the backstory behind Garfield’s protracted death and Guiteau’s conviction and execution for the crime.

Garfield won election in the 1880 presidential election almost by accident. He had gone in to stump for another candidate, John Sherman, but his speech to the Republican National Convention was deemed so electrifying that he won the party’s nomination in Sherman’s place. Yet he was one of America’s most inconsequential presidents, and this was entirely due to the activities of Guiteau, a mentally ill drifter who conceived the idea firstly that Garfield’s victory was down to his own activities, and secondly, once he had decided that the president was a disappointment and a disgrace, resolved to assassinate him and live on in the annals of history that way.

The central joke of Death by Lightning – which takes its title from Garfield’s inadvertently apposite remark that “assassination can be no more guarded against than death by lightning. And it is best not to worry too much about either one” – is that both men disappeared into obscurity far faster than either might have imagined. For Garfield, played here in a steady, measured performance of quiet upright decency by Michael Shannon, the chance not to be remembered may have been a blessing of sorts. But for Guiteau, who had wildly grandiose fantasies of power and importance unrelated to any achievements of any kind, the slide into obscurity would have rankled far more than anything that Garfield did, or did not, do.

The narrative of Mike Makowsky’s show is divided into two interconnected but separate strands, each given roughly equal screen time over the four episodes. The first is relatively conventional politicking, exploring how Garfield is beset by power brokers and cynics including Shea Wigham’s Republican bigwig Roscoe Conkling and, uproariously, Nick Offernan’s Chester A. Arthur, a Falstaffian opportunist (catchphrase: “Music! Fighting! Sausages!”) who nonetheless is well-versed in the Machiavellian arts. All this is gripping enough, shot through with wry humor and some magnificent facial hair, but, in truth, it is unlikely to change anyone’s opinion about the interest levels of 19th-century political shenanigans.

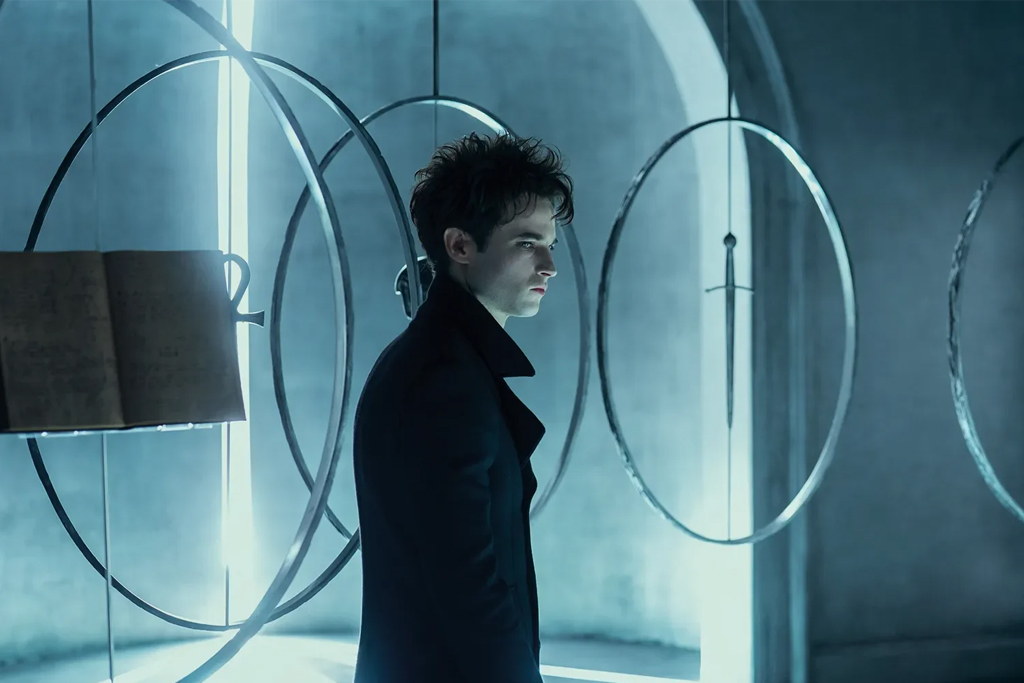

The other storyline, however, concerns Guiteau and is far more arresting, thanks to the heroic work of Matthew MacFadyen in the lead. While Succession took MacFadyen into the big time in the United States, thanks to his superb performance as the sniveling, wretched bootlicker Tom Wambsgans, viewers in his native Britain have been treated to a series of anti-heroic performances by the actor in recent years, including the “coughing major” Charles Ingram in Quiz and the disgraced politician John Stonehouse in Stonehouse.

What MacFadyen excels at is playing characters who laugh too long and hard at their own jokes, whose façade of confidence and rectitude disappears at the slightest nudge, and whose conniving soon teeters over into incompetent blundering. His Guiteau isn’t played just for laughs – although the scenes depicting him as the only man not getting any action in the free love commune of Oneida are uproarious – but as someone who has the delusional idea that he, too, can be a great man, without putting the hours in: a fantasy definitively upended when he comes face to face with a kindly, bemused Garfield, in one of the show’s most memorable scenes.

I sat down to watch Death by Lightning expecting raucous black comedy, but it’s something more complicated than that. In its relatively brief running time, it makes some effective comparisons between the pork barrel conniving of the late 19th century and the present day and gives Garfield the dignity that he deserves. But it’s MacFadyen who’s the stand-out here, combining grimy desperation with a spurious belief that he should be given far greater credit than he has ever deserved. Guiteau may have been lost to history, but if there is any justice, the Emmys and Golden Globes next year will not forget his performer’s sublime work here.

Leave a Reply